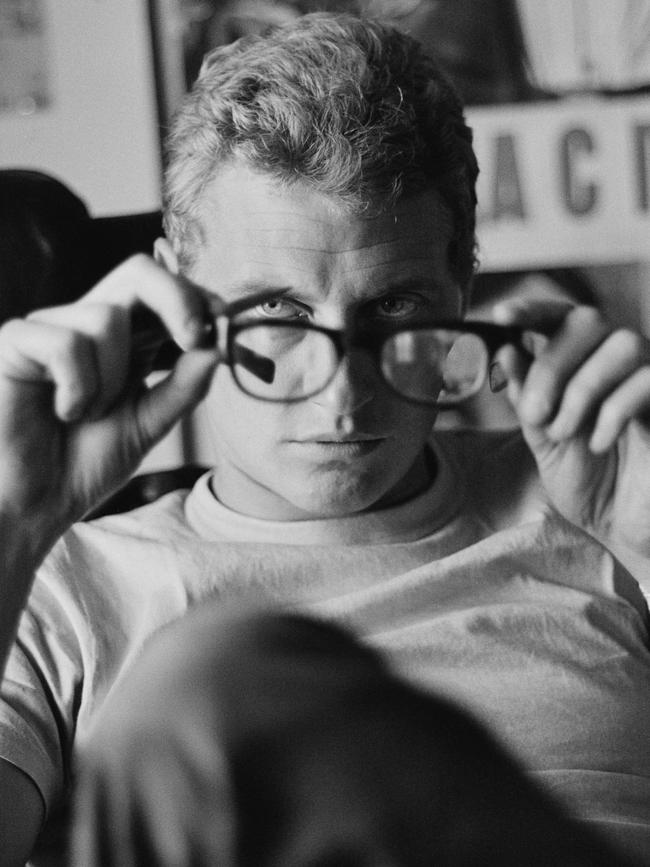

Obituary: Derek Boshier, pioneering British pop artist

Pop artist Derek Boshier’s Special K paintings mused on the Americanisation of UK culture and prefigured Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup pictures.

When Derek Boshier left school at 15, his headmaster asked him what he intended to do. “Well, my best friend Don’s father owns a butcher’s shop,” he replied. “He said if I was leaving school I could work for him.”

“What about doing art?” his headmaster asked. Nonplussed by the idea that art could be anything more than a frivolous hobby, Boshier spluttered: “What’s that?” However, he enjoyed “messing about” with paint and brushes in his Thursday afternoon art classes and when the idea of going to art school was put to him, all thoughts of becoming a butcher’s boy were put on hold.

Three months later he began at Yeovil School of Art and from there he went on to the Royal College of Art, where fellow student David Hockney was to become a lifelong friend. Together with a handful of other RCA students they helped to shape the emerging British pop art movement. “We didn’t know that at the time, of course. We were just kids having fun,” Boshier said.

The significance of what they were doing only began to dawn on him when he was featured in Ken Russell’s seminal 1962 BBC television documentary, Pop Goes the Easel, alongside Peter Blake, Pauline Boty, who was to die just four years later, and Peter Phillips, who filled in for Hockney, who missed the filming as he was in New York. Suddenly, everyone was talking about a new phenomenon called pop art.

In the film, Boshier talked about the manipulative power of advertising and the Americanisation of British culture, recurring themes in his early work. A 1961 picture called England’s Glory showed the eponymous patriotic matchbox being invaded by the Stars and Stripes but perhaps his best-known painting from the period was Special K, featuring a large letter K lifted from the packet of the Kellogg’s cereal.

For Boshier, it was a metaphor for the way Britain seemed ready to consume whatever America had to offer. “You’d start the day under American influence at the breakfast table and then find yourself going through the rest of the day in the same vein,” he noted many years later when, ironically, he himself had become an American citizen.

The parallel with Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans was inescapable, although Boshier’s Special K predated it by a full year.

By the time the Beatles arrived in London in 1963, Boshier was established on the art scene and went on to play a seminal part in the collision of pop art and pop music. He found a particular affinity with John Lennon, who was also a former art school student, of course, and spent long nights at his flat in Kensington talking about art. Boshier reported that they shared a love for Hieronymus Bosch.

On one such evening Lennon told him he was planning to buy his first car. Boshier offered to sell him his green Triumph Herald convertible parked outside. Lennon paid him “a hundred quid” in cash. Boshier took a taxi home.

He was also friends with photographer Tony Armstrong-Jones, who on marrying Princess Margaret had become the Earl of Snowdon. One night he invited Boshier to a soiree at Kensington Palace, where a joint was passed around. Boshier, who had the princess to his right, took the joint from his left and passed it immediately to her. “Please,” he insisted. “Royals first.”

His closest association in the world of pop music was with David Bowie, who became a friend and whose art collection, which after his death sold at Sotheby’s in 2016 for $US41m, included many of Boshier’s works.

They met in 1979 when Boshier curated a photography exhibition at the Hayward Gallery on London’s South Bank. Titled Lives: An Exhibition Of Artists Whose Work Is Based On Other People’s Lives, it featured works by David Bailey, Hockney and Brian Duffy, who had shot the cover of Bowie’s 1973 album Aladdin Sane.

Impressed by the exhibition, Bowie asked Duffy to arrange a meeting. “When he told me to come and meet a good friend who he knew I would get on with, I thought I was being set up for a blind date,” Boshier recalled.

Bowie asked him to design artwork for his 1979 LP Lodger. The image he created for the cover depicted a dishevelled Bowie seemingly falling through space, although in fact he was lying on a trestle table. The inner gatefold featured a Boshier collage of images, including the corpse of Che Guevara.

He also designed the cover of Bowie’s 1983 album Let’s Dance, which depicted the singer in boxing gloves with Boshier’s painting, A Darker Side of Houston, projected on his bare chest.

Two months before Bowie died in 2016, he sent Boshier an email saying how much he had enjoyed his recent book, Rethink/re-entry. It ended with the words: “Your work cascades down the decades and is utterly real and convincing. You really are a master.”

“I thought, ‘I’ll wait a bit and then I’ll do a drawing and send it to him’,” recalled Boshier, who, like almost everyone else, was unaware Bowie was terminally ill with liver cancer. The drawing was never sent.

Derek Boshier was born in 1937 in Portsmouth and grew up in Dorset, where his father, a former Royal Navy seaman, was a caretaker at Sherborne School for Girls. Growing up, he was regaled with tales of serving on the British ship sent to Yalta to rescue the surviving members of the tsar’s family after the Russian Revolution.

He enjoyed a solidly unpretentious upbringing and cited his working-class origins as the “strongest influence” on his art but to the surprise of his parents he passed the 11-plus and went to the local grammar school.

Two years of national service in the Royal Engineers interrupted his studies at art school and after graduating at the RCA he took a year out to travel around India on a scholarship. On his return to London, he had a long spell teaching at the Central School of Art and Design, where one of his pupils was John Mellor, later known as Joe Strummer of the Clash. “I remember him sat in front of the class with a wooden guitar singing Blowin’ In The Wind,” Boshier recalled. “He would say, ‘Call me Woody, man’ because his hero was Woody Guthrie.”

A few years later, Boshier met his former pupil outside an Oxford Street shoe shop, dressed all in black and wearing Doc Martens and surrounded by a posse of similarly dressed Clash fans. When Boshier hailed him by his old nickname, Strummer told him: “I’m not called Woody, I’m Joe now.” Two weeks later he received a call asking if he would like to design a Clash songbook featuring lyrics to 20 of the group’s songs. When he asked for details of the brief he was told “you can do what you f..king like”.

Boshier adorned the 48-page book with photos, line drawings and punk-style graphics illustrating the themes of Strummer’s songs, and it was published in conjunction with the band’s 1978 album Give ’Em Enough Rope.

In the late 1960s he abandoned painting and produced sculptures in Perspex and neon, and during the 1970s he turned to photography, film and installations, although by the end of the decade he had returned to painting. In 1980 he moved to Texas, joining the faculty at the University of Houston, where his paintings of emasculated cowboys, subverting the macho stereotype, aroused some controversy. He returned to London in the early 1990s before emigrating again in 1997 to Los Angeles to take up a position with the California Institute of the Arts. When he fell ill a few years later with cancer of the tongue, Hockney sent him a cheque for $25,000 to cover his medical bills.

Boshier is survived by his partner, Thelma Gaskell, and by daughters Rosa and Lilian from his marriage to artist Patricia Gonzalez.

His work can be found in permanent collections from the Tate to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and was most recently celebrated in last year’s retrospective exhibition, Image in Revolt.

Boshier preferred to call himself a “populist artist” rather than a pop artist. “I’ve always been conscious of ensuring that every work that I make is not just for the art world but is actually accessible.”

Derek Boshier, artist. Born June 19, 1937; died aged 87, September 5, 2024.

The Times