Willie Phua obituary: war cameraman who was at Tiananmen Square

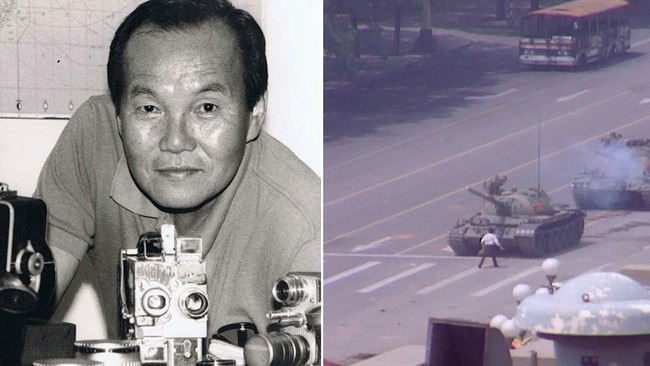

Lying on a tenth-floor balcony at the Beijing Hotel, he filmed the young ‘Tank Man’ blocking vehicles in 1989.

War cameraman who, lying on a tenth-floor balcony, filmed the young ‘Tank Man’ blocking vehicles in Tiananmen Square in 1989

Willie Phua, a Chinese-born Singaporean TV news cameraman for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), could hardly believe his eyes when he poked his Beaulieu R16 film camera through a gap beneath his balcony on the tenth floor of the Beijing Hotel on June 5, 1989. Over the previous 48 hours, he had filmed the massacre of at least several hundred Chinese students on Tiananmen Square by soldiers and armoured vehicles.

This time, he was filming on his belly because machinegunners on an approaching column of tanks were firing sporadically at buildings, including his hotel, along their route. Given the state of his nerves after filming the massacre, he at first thought he must be hallucinating. He told his two ABC reporters, also crouched on the balcony: “Hey, guys, come and look at this.”

“We saw this column of tanks coming in, and we saw this young man out of nowhere who came in and stepped in front of the tank,” Phua later told the Australian foreign correspondent Bob Wurth in the latter’s 2010 book about Phua, Capturing Asia: An ABC Cameraman’s Journey Through Momentous Events and Turbulent History. “The tank would go to the left, he would go to the right – and then he climbed onto the tank and talked to the guy in the turret … Then he climbed down, and finally two men – I don’t know whether they were his friends or the government – whisked him away, and we never heard from him.”

It was never established whether fellow students had pulled the young man away or whether Chinese security officials had arrested him. His fate remains unknown.

The young man Phua filmed became known around the world as “Tank Man”, a white-shirted young Chinese man carrying two shopping bags and believed to be a student upset by the massacre of the previous hours. Although two American TV network cameramen also got footage of the incident, Phua’s images, due to his Australian network ABC’s syndication deal with Reuters/Visnews, the BBC and NBC of the US, were broadcast around the world and are re-shown to this day.

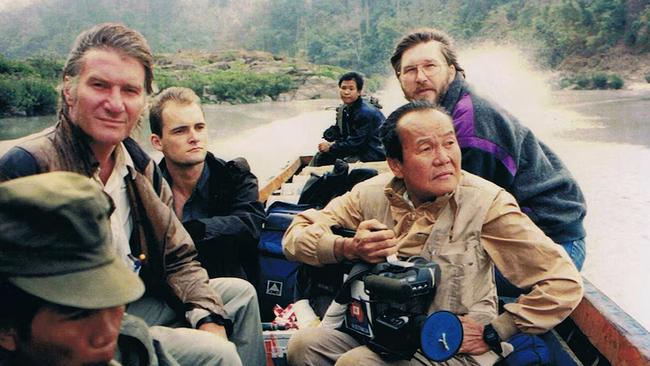

But it was only after the turn of the century that Phua got personal recognition, thanks to the Australian foreign correspondents who had worked with him, including Max Uechtritz and Peter Cave, who were both with him on the hotel balcony on that day. Phua always considered the Australian war reporters, photographers and cameramen he had worked with and mentored as “my Australian family”.

Phua Tin Tua, known throughout his career as Willie, was born in 1928, in the village of Bai Siew Swee on the island of Hainan, China’s most southerly province. When he was five, he moved with his father, Phua Gee Wah, and mother, Phua Tan Hee, to the British colony of Singapore, only to find that Singapore was racked by horrific typhoons and the threat of a Japanese invasion.

After the Battle of Singapore, Japan invaded the British colony in 1942 and drove out the British and its colonial allies, mostly Australian, the largest British surrender in history. Phua retained vivid memories of the Japanese occupation after he picked up the still-hot fragments of a Japanese bomb. “I was a little bit frightened but also excited. This was something exciting for a boy of my age. It was the first bombing attack on Singapore. We didn’t know the Japanese were coming here until these bombs fell,” he told his biographer Wurth, recalling that he and his mother sheltered in a rat-infested storm drain and saw defeated British and Australian soldiers weeping in the same gutter and awaiting capture.

Young Phua, aged 14, tried to help put food on the family table by trading in cigarettes with the Japanese occupiers. For the same reason, his mother took a job as a cook in the kitchens of various Japanese brothels in Singapore, where the invaders took advantage of Korean “comfort women” they had kidnapped. “I did errands for the [Korean] girls and would also buy things for the Japanese soldiers. The girls always seemed to want food. When the women had a Japanese client, especially if they had found a captain or a higher rank, they would say ‘I’m hungry’ and ask the soldiers to buy noodles for them.”

After Japan surrendered to the Allies in September 1945, Phua bought first a still, and later a film camera. In 1963, he got a job with Radio Television Singapore (RTS), covering anti-colonial riots in Singapore, Malaya (later Malaysia), Borneo and Indonesia.

Having started covering the Vietnam War in the late 1960s, Phua became affectionately known by foreign reporters, photographers and cameramen as “the Fat Chinaman” or “Pork Chop” the latter being an Australian nickname for beer, of which he was fond at the end of his day’s work.

He covered wars or other significant stories from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia to India, Pakistan, the Philippines and much of southeast Asia. In 1971, working with the Australian ABC journalist Athol Meyer, he was heavily shelled at an American base in Vietnam’s Central Highlands while filming the hardships and dangers faced by American “grunts” on the front lines.

That year, he was also sent to the newly created nation of Bangladesh, previously East Pakistan, where violence was rife. Don Hook, an Australian reporter on assignment with him, recalled, “From the roof of the InterContinental Hotel in Dhaka, Willie shot graphic footage of horrific events in the street below. Soldiers had deliberately set fire to a newspaper building. As newspaper staff ran from the blazing building there were bursts of automatic fire followed by screams and calls for help.” Hook, Phua and other international reporters were arrested and ordered out of the country. Around this time Chua married a fellow Singaporean, Cindy Chong Chai Sin.

In April 1972, he was almost killed when a South Vietnamese military patrol boat he was aboard came under heavy Viet Cong machinegun and rocket fire on the Saigon River. His sound man, who was sitting beside him, was severely wounded in the leg. The boat’s South Vietnamese gunner lost a leg to machinegun fire.

Phua also became a trusted friend of the Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi, who called him “my good Chinese friend”, and he was one of the few photojournalists allowed to photograph her body on her deathbed after she was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards in 1984. He went on to film the subsequent street lawlessness and massacres of Sikhs in Delhi, along with the Australian correspondent Bruce Dover. “There was a mob hauling the Sikhs from their homes and breaking their legs so that they couldn’t run away, then pouring oil over them to burn them alive,” Dover told Australian news media. “They were mostly Sikh men but also Sikh boys. Willie filmed the mayhem. I remember seeing bodies everywhere. It was so gruesome.”

Phua’s footage of truckloads of Sikh bodies, many of them children burnt to death, was shown around the world. And the Australian TV crew’s longtime driver, fixer and interpreter in Delhi, Joseph Madan, said Phua had saved his life on several occasions by stepping in front of angry mobs, using his “neutral” Chinese looks and press credentials to keep them from killing Madan.

Phua worked as a cameraman until the early 1990s when he realised his back could not tolerate the weight of a camera, its lens, lights and other equipment. It was while trying to film climbers on Mount Fuji, Japan, in 1993, aged 65, that he recognised his body could not keep up with those he was filming. He retired that year and in 1996 he was awarded the Order of Australia. He is survived by his wife, Cindy. Two of his surviving nephews, Sebastian Phua and Joe Phua, are also TV news cameramen, the latter for the BBC, where he has worked with the world affairs editor John Simpson in war zones.

Trevor Watson, one of the young Australian correspondents who worked with Phua, wrote on Facebook: “My first assignment with the legendary Willie Phua was in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province during the Soviet occupation of neighbouring Afghanistan. Before leaving our New Delhi Bureau, the ABC’s Asia Manager, Peter Hollingshead warned me not to get Willie into trouble. ‘Young reporters like you are a dime a dozen,’ Hollingshead warned, ‘but there is only one Fat Chinaman …’ Knowing Willie Phua was the key to fraternity membership. I’ll be raising a ‘pork chop’ (beer) to the Fat Chinaman tonight. The world is now a poorer place without him.”

(Willie Phua (Phua Tin Tua), TV news cameraman, was born on February 20, 1928. He died after a long, undisclosed illness on December 17, 2024, aged 96)

The Times