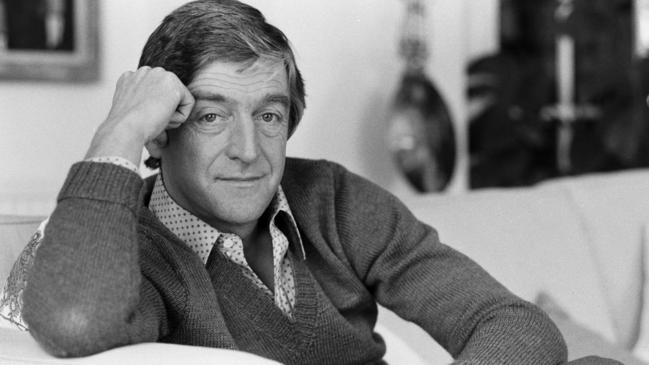

Michael Parkinson, a folk hero even after interview leaves a slightly sour taste

Michael Parkinson hated snobbery about his background, as he revealed in a meeting of two Yorkshiremen over lobster thermidor and a perfectly chilled Chablis Premier Cru ’94.

Of all the professional Yorkshiremen operating in the effete south, Michael Parkinson was the master. A true craftsman. It wasn’t enough for him to do what other PYs – such as Harold Wilson, Ted Hughes and Alan Bennett – did, namely cling on to their accents despite the odds. He used his Yorkshireness as a flinty tool with which to disarm his chat show guests.

He inhabited it. Was its embodiment. “I’m Yorkshire,” he liked to say by way of an excuse when occasionally accused of some wokish transgression.

As a Yorkshireman myself I considered him to be something of a folk hero when I was growing up. And when I got a chance to interview him, over lunch at Bibendum, naturally – when Yorkshiremen moan about how tough it was oop north they like to do so over lobster thermidor and a perfectly chilled Chablis Premier Cru ’94 – I tried not to be like Mrs Merton, who broke away from her prepared interview questions, chewed her lip earnestly and blurted out: “Oh Parky, I think I love you.”

We talked about cricket, of course, a shared passion. Like all professional Yorkshiremen, he lived for it. He was a useful left-handed opening batsman in his youth, had a trial for Yorkshire, and numbered those PYs Geoffrey Boycott, Dickie Bird and Freddie Trueman among his friends. Boycott, indeed, called him “the soul of Yorkshire”.

And over that lunch Parky laid the bluff, speak-as-I-find Yorkshireman stuff on thick. I counted afterwards and found that he had used the word “bloody” 14 times, “bugger” eight (including two “daft buggers") and “bollocks” three.

He was most affecting when the conversation moved to his father. I think he kept his Yorkshireness going because he needed to remind himself constantly that he was Jack Parkinson’s lad, an only child who grew up in a council house in the Yorkshire pit village of Cudworth, near Barnsley.

His father, one of 17 children, had died in 1975 and Parky told me when we met in 1997 that he had recently been having recurring dreams about him. “Nice, pleasant dreams, where he’s part of the family still. But the awful thing is, when I wake up, it comes as a shock that he’s not alive.”

When young Michael had expressed an interest in following his father down the pit, he was promptly ushered into the Grimethorpe cage and lowered to the depths, but not to encourage him. The sight of men working on their bellies in a 3ft-by-6ft (about 1m-by-1.8m) seam, breathing in coal dust, terrified the young lad, as his father had intended. When Michael mumbled that he didn’t fancy working there after all, his relieved father told him: “If you ever change your mind, I’ll kick your arse all the way home.”

“It was an awful bloody life,” Parky told me. “My father used to ‘tip up’ and be given back half a crown a week from my mother. People talk about pressure today. I mean, you hear some frigging footballer complaining. Pressure? My father had to be up at four. You didn’t get paid till you reached the seam. You’d been walking for three bloody hours before you got there, then you’d spend the day on your hands and knees a mile underground.”

When I met him he had just been back to Grimethorpe, only to find that the mine had been concreted over and half the shops boarded up. The trip had left him with mixed feelings. Mining is a brutish way to earn a living, he concluded, and if other employment had been found for his old community he wouldn’t have mourned its passing. But he had warm memories of waiting outside the Working Men’s Institute for his father, listening to the “bloody marvellous” singing inside.

At one point he looked around the restaurant and recalled that whenever he took his father to such a place – long after Parky had become one of the most famous faces on television – he would never dare show him a menu with the prices on or let him see the bill. “But he wouldn’t be bothered by it. We were once in a place like this and he came out of the toilet and said: ‘Ay up, there’s a lad in there who knows you.’ And it turned out he’d been standing next to a stranger at the urinal and just came out and asked, ‘Do you know my lad, Michael Parkinson?’ ”

His abiding memory of his father was his laugh. “He would embarrass me in movies by laughing so loud he would be asked to leave by the manager.” Parky inherited some of that ability to laugh helplessly, as he showed with his various encounters with Billy Connolly, a comedian he more or less discovered. He knew when to let performers perform, though he always rather resented being remembered most for being attacked by Rod Hull’s Emu.

His greatest interviews, for my money, were those with Kenneth Williams because they revealed the comedian’s true cold side. I asked him about them. “I didn’t like Williams and he didn’t like me,” he said. “And it showed. Towards the end we were like two sniffing dogs. The first time we met he wrote in his diary that I was a vulgar north country nit.”

Being patronised by southerners was something Parky hated. He knew he was just as good as them, if not better, and this explained his stubborn refusal to “go native”.

Despite the urbane, southern media world he had inhabited for much of his adult life, he never succumbed to liberal correctness. At one point he told me the reason there hadn’t ever been a successful female talk show host was that “they find it difficult to unhook their corsets and let the cellulite out”.

Later, to illustrate why the timing of a joke is more important than its content, he repeated a Bernard Manning joke about racial minorities, knowing how provocative it would seem in print but not really caring.

As for those unsoftened northern vowels he said: “I kept my accent because it was economically viable to do so. No sense in changing it. When I started at Granada TV in the Sixties everyone had a northern accent. It was the same time as the Beatles and all the northern playwrights and actors. Tom Courtenay. Albert Finney. People who spoke posh were trying to affect Yorkshire accents. Before that I would have been lucky to get a job as a doorman at the BBC. There was a new hierarchy. Jack was becoming as good as his master.”

I felt the interview had gone well but, Yorkshiremen being Yorkshiremen, when it appeared in print, Parky took exception to a passage where I had implied that he thought he was “the best bloody interviewer in the world”. He denied that he had implied this and complained in rather strong terms to my editor, perhaps hoping to get me fired. It left a slightly sour taste.

The exchange had been prompted by him saying that Roy Plomley, who he replaced as the host on Desert Island Discs, had been “the worst bloody interviewer in the world”.

It seemed that Plomley was still a prickly subject for him because “his widow began a one-woman campaign to preserve the memory of her husband and she started complaining, ‘What is this crude northern oik doing walking on my husband’s grave? The accent is too common.’ I was too wily to respond then. But she was nasty.”

And by nasty he meant snobby, about his Yorkshireness. “Would I have been different brought up in genteel Surbiton?” he asked. “The answer would be yes. Very different indeed. Down here is still in my mind where the fat cats are. And it’s good to succeed and become a fat cat. Why not? I don’t trample on people. I’ve never been a jealous type. But I’m competitive and I have encountered snobbery about my background from people at the BBC.”

We did reconcile, sort of, a few years later when a mutual friend, Tim Rice, invited us both to join him for lunch at the Garrick. Sadly, because of a previous commitment, I couldn’t go, and I regret that now because, when all is said and done, Parky was still a hero figure to me. Rest in peace, you daft Yorkshire bugger.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout