The final word on talk king Michael Parkinson

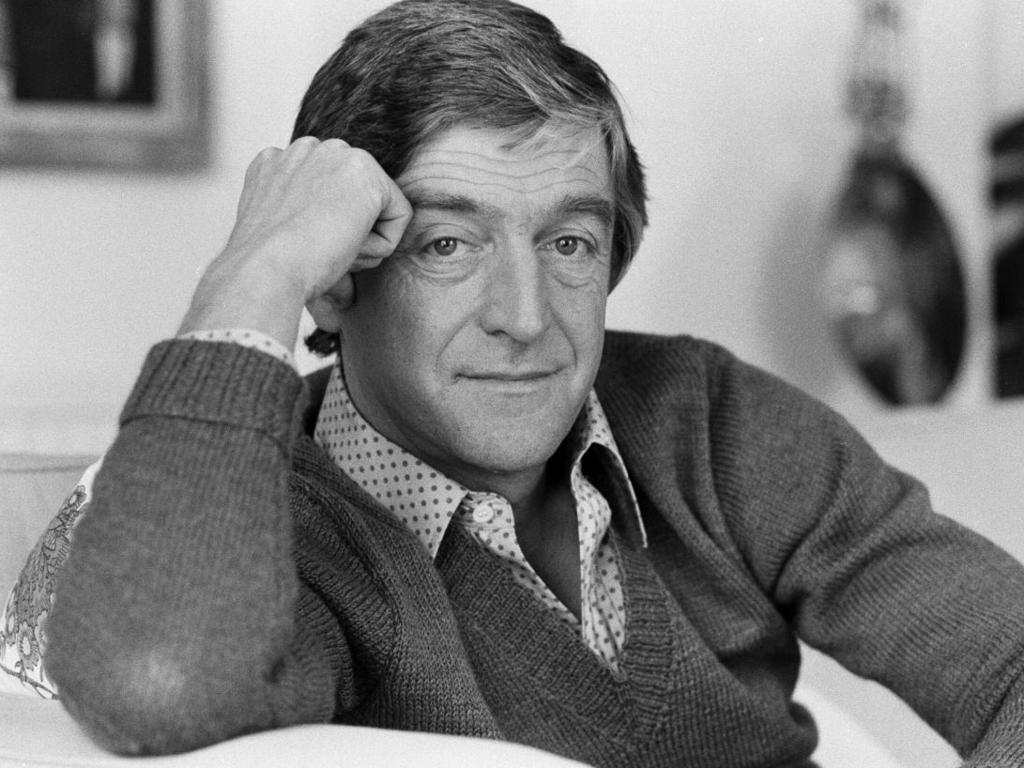

His trademarks were his warmth and enthusiasm, and a recognition that the first requirement of a successful interviewer was to be a good listener.

Sir Michael Parkinson, journalist and chat show host

Born March 28, 1935.

Died after a brief illness August 16, 2023, aged 88

When Michael Parkinson was 19, he was a good enough batsman to keep the young Geoffrey Boycott out of the Barnsley cricket team. As a left-handed opener he made a century in a league match against Harrogate and a fifty in the next game, ensuring that England’s future batting hero was left to fume in the second XI while Parkinson took his place and dreamt of sporting glory.

Long after, he was still citing his brief summer of cricketing supremacy as his proudest achievement and giving every impression that he would have happily swapped his television career to have joined Boycott in the England team. Instead, a disastrous trial with Yorkshire put paid to his ambitions when his stumps were repeatedly shattered by Fred Trueman.

He attended the trial with Dickie Bird, later the international umpire, who recalled his best friend’s rejection. “What does tha’ mate, Parkinson, do?” Arthur Mitchell, the Yorkshire coach, asked Bird. “He works on the local newspaper,” Bird replied. “I’ve some advice for him,” said Mitchell. “Tell him to stick to journalism.”

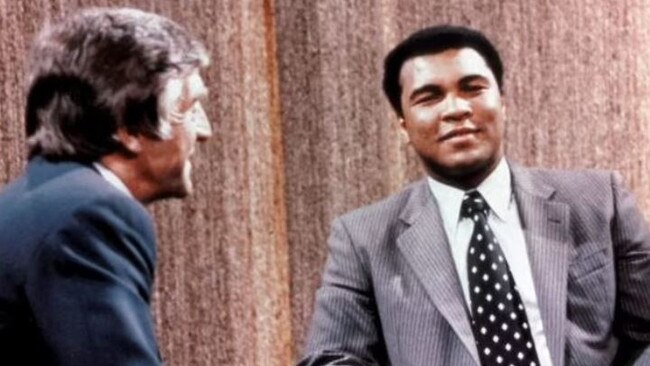

Parkinson took the hint and if journalism was second best as a career choice, he pursued the job with relish. As a chat show host he interviewed and befriended many of his sporting heroes, from Boycott and Trueman to George Best and Muhammad Ali.

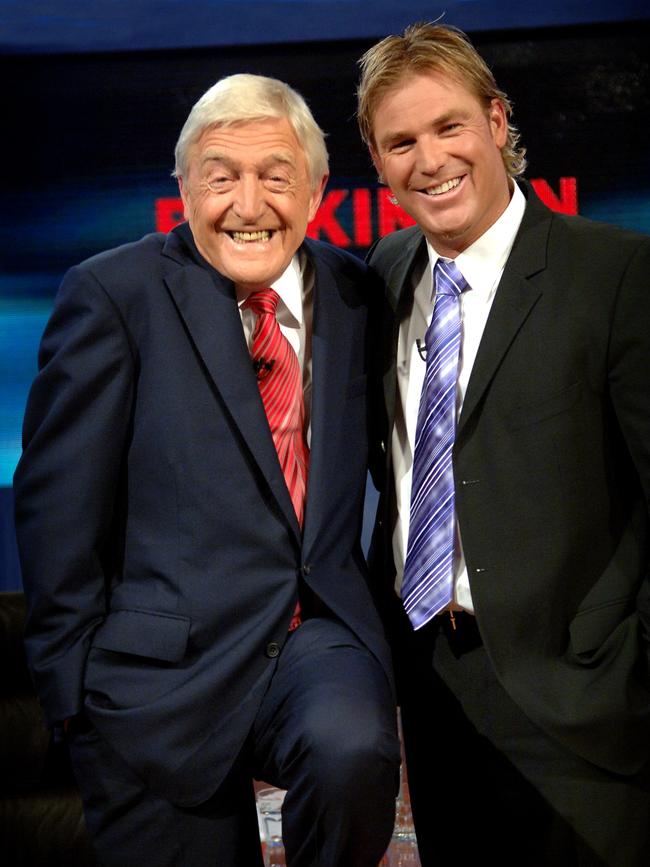

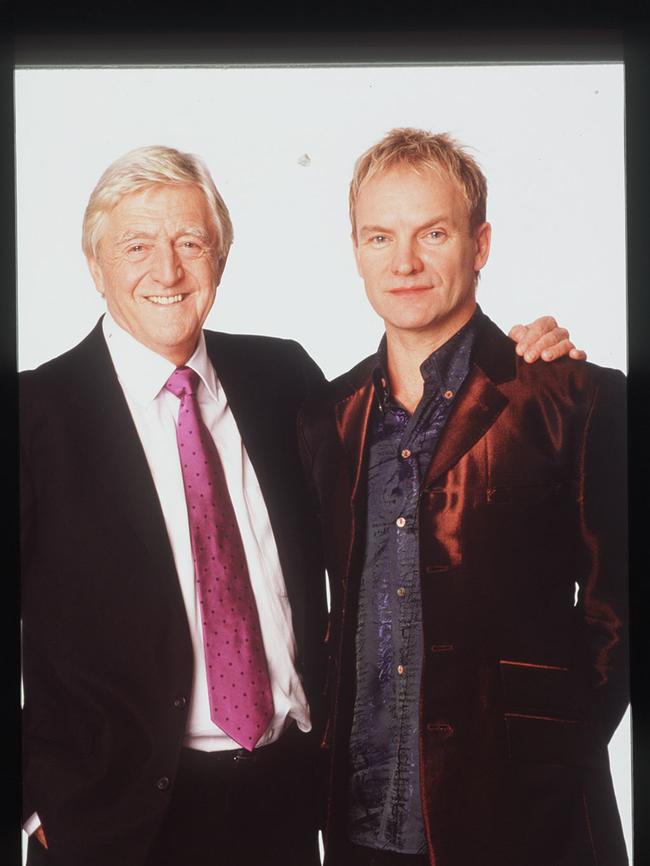

Yet such gods of field and ring were only the tip of a celebrity iceberg of guests who appeared on the TV show that bore his name. Between 1971 and 2007, Parkinson ran for more than 500 episodes, during which time he interviewed more than 1,500 celebrities.

He flirted with Shirley MacLaine and Raquel Welch, cried with laughter when interviewing Tommy Cooper and Kenneth Williams, gave full largesse to Barry Humphries’s alter egos Dame Edna Everage and Sir Les Patterson, appeared to be in awe of the intellect of the philosopher Jacob Bronowski and the poet WH Auden, was mesmerised by Gene Kelly and James Cagney, came on all fatherly to David Beckham and was famously bullied by Rod Hull’s puppet Emu, which wrestled him to the ground.

His trademarks were his warmth and enthusiasm, and a recognition that the first requirement of a successful interviewer was to be a good listener. Absorbed by what his guests were saying, he displayed an engaging array of unconscious mannerisms, scratching his neck, flicking his ear, running his hand through his hair and even picking his nose, as if he had completely forgotten he was on television.

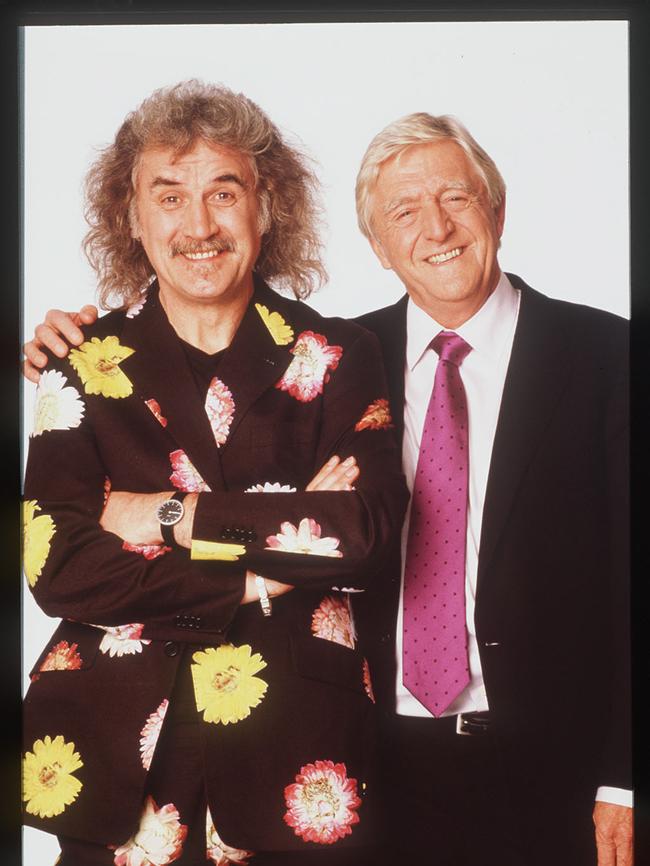

Viewers loved him as an affable, down-to-earth Yorkshireman and as Parkinson soared in the ratings - at its peak the show drew an audience of 12 million - its presenter vaulted in the public’s affection as “the people’s interviewer”. He had his favourites - Billy Connolly appeared 15 times - and his style was comfortable and conversational, even cosy and at times bordering on the fawning.

The charge was less than surprising, for many of his subjects were indeed personal heroes from his boyhood. On interviewing Orson Welles, he called him “Mr Welles” and told him he was doing so out of respect for his “great talent”. The director told him: “I’d say you were talking bulls***.”

Among those he admired most, he cited only Frank Sinatra, Katharine Hepburn and the cricketer Sir Donald Bradman on a shortlist of “the ones that got away”. Bob Dylan also eluded him, although they met once when they were staying in the same hotel.

“Eggs over easy and coffee,” Dylan told him when Parkinson approached him at breakfast and told him that he loved his music. The one place Parkinson was not the world’s most famous TV interviewer was America, and Dylan had mistaken him for a waiter.

Parkinson’s technique was sometimes criticised as soft, but his riposte to such brickbats was robust. “It’s not bloodsport and I am not interviewing war criminals or paedophiles,” he pointed out. “I am interviewing people whose only crime is to entertain people.”

Yet he was not afraid to ask difficult questions and over the years there were some infamous confrontations, among which the antics of “that bloody bird”, as he for ever after referred to Emu, were relatively tame.

His bouts with Ali were fabulous encounters, including the occasion when the boxer launched into an extraordinary tirade that left Parkinson lost for words, after he had challenged him on his religious beliefs. “He could be extraordinarily rude and arrogant, but also childlike, funny and mischievous,” Parkinson recalled. “A difficult man to know, but I loved him in all his moods. I went in with him four times and I lost on every occasion.”

Ali also enjoyed their sparring. “I used to come here a long time ago to fight a guy called Parkinson,” he quipped when he made his final appearance on BBC Television in 1999 to receive the Sports Personality of the Century award.

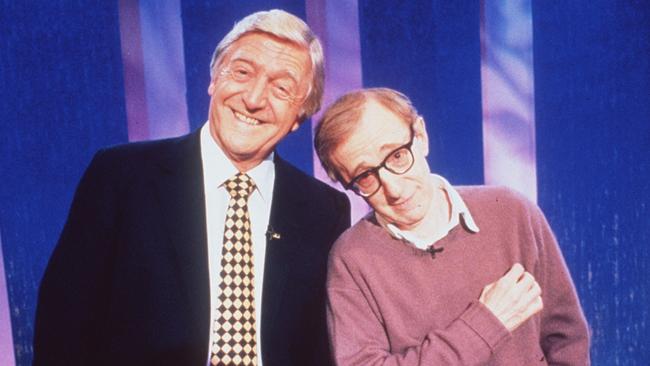

John Wayne bristled when Parkinson questioned his dubious role during the senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunt of communists in postwar Hollywood. Woody Allen almost walked out when Parkinson probed into the custody battle for his children and asked about his marriage to his step-daughter Soon-Yi, before he diplomatically apologised and changed the subject.

Tony Blair was discomfited when pressed on the Iraq war and eventually told him he would be judged by God for his actions rather than by a chat show host. He outraged Helen Mirren and invoked feminist wrath when he introduced her as the “sex queen” of the Royal Shakespeare Company and asked if what he euphemistically called her “equipment” hindered her being recognised as a serious actress. Decades later she was still calling him a “sexist old fart”. He responded with a curt: “I’m Yorkshire.”

Equally notorious was a confrontation with Meg Ryan in which the American actress stared icily at him and refused to give anything more than the briefest answers. In Britain to promote her erotic thriller In the Cut, she took umbrage when Parkinson asked about the change from her typical romantic comedy roles. In exasperation at one point he asked her: “What would you do now if you were me?” She replied: “Why not wrap it up?”

He counted it as his most difficult moment in 40 years on TV. “People loved that moment, of course, because they love to see that kind of embarrassing situation. But I should have closed it. She was an unhappy woman. I felt sorry for her. What I couldn’t forgive her for was that she was rude to the other guests,” he said.

An unrepentant Ryan criticised his paternal manner. “He’s a nut,” she said. “I felt like he was berating me for being naked in the movie and I thought, ‘Are you like a disapproving dad? Back off, buddy’. I was so offended by him.”

In a 2006 poll of the “most shocking” TV chat show moments, the spat came third behind Grace Jones slapping Russell Harty and David Icke pronouncing himself to Terry Wogan as a “son of Godhead”.

To the viewing public Parkinson was simply “Parky”, a warm and kindly national uncle, but off-screen he had a well-developed sense of his own worth, did not suffer fools gladly and expected to get his own way. He later admitted that he struggled to see the funny side of being assaulted by Rod Hull and Emu in 1976, bemoaning in later years: “The only thing I’ll ever be remembered for is being attacked by a f***ing emu.”

At the height of his popularity he quit the BBC in 1982 after the corporation had rejected his suggestion that his show should move to five nights a week.

In 2004 he walked out on the corporation for a second time because he could not agree on a suitably prominent alternative primetime slot for his show after the return of Match of the Day to its traditional Saturday evening slot. He took the show to ITV, where it was broadcast with an identical set, theme tune and format to the BBC edition. He was paid pounds 1.5 million for a two-year deal.

He was sensitive to criticism and at times of stress or boredom in his life he was prone to drinking heavily, giving up only after his wife Mary told him that it made him “ugly”.

In later years he was scathing about celebrity culture and what he saw as a decline in television standards. “The currency of being a talk show host has been reduced over the years as they’ve experimented with talk shows involving the kind of people you wouldn’t normally expect to be talk show hosts,” Parkinson noted grumpily. “They are working on the assumption that what I do for a living can be done by anybody. I’m quite offended by that - and I’m quite agitated.”

In old age he appeared to take pride in seeing himself as a man out of time, although he retained sufficient self-awareness to recognise that he was in danger of “coming on like a curmudgeonly old bastard”.

Yet as the years went on, his agitation seemed only to increase. “Instead of getting people who can do the job, they want celebrity interviewers with plastic boobs or who have played football. I’m not being pompous, but it reduces the currency of what I do,” he harrumphed.

His interviewing role models were old-school types such as Cliff Michelmore, Alan Whicker and David Frost, and he had no time for the innuendo and showboating of those who followed in his wake. “People like Graham Norton and Jonathan Ross don’t do talk shows. Theirs are comedy shows, which they are very good at, but their guests are foils for their humour. I don’t see anybody coming up to do my kind of show,” he said.

He was convinced that the quality of stardom had also declined and noted that interviewing Madonna could never offer the same thrill as talking to Ingrid Bergman or Fred Astaire, viewing this as an inherent fault in the nature of modern celebrity rather than a reflection of his own advancing years and nostalgic belief in a long-gone “golden age”.

When he finally interviewed Madonna in 2005, he admitted he had been wrong and described her as “absolutely brilliant”, although he was staggered by the size and nature of her entourage. “One of them had a long, thin stick in her hand and at the end was a cotton bud and she was following Madonna around,” he recalled. “And then Madonna turned towards her, stood still and the girl put the cotton bud up Madonna’s nose to look for bogeys.”

He joked that when he retired he wanted a job as “Madonna’s bogey finder” but could not help reflecting that when he had interviewed the likes of Bergman, Lauren Bacall and Bette Davis, they had all managed perfectly well without an army of flunkies and gofers.

He was also venomous about reality TV and the nonentities whom it turned into “stars”. When Jade Goody, who made her name on the show Big Brother, died from cancer at the age of 27, he dismissed her as “barely educated, ignorant and puerile” and claimed that she represented “all that’s paltry and wretched about Britain today (Friday)”. He had crossed the line between northern bluntness and tactless, gratuitous insult.

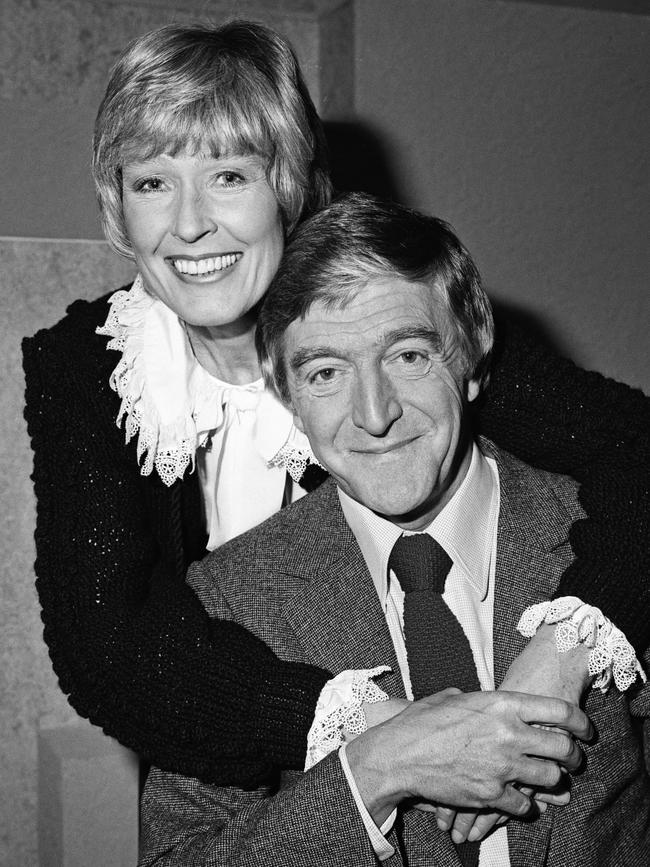

He was married for more than 60 years to Mary Heneghan, a schoolteacher whom he met on a double-decker bus in Manchester and later became a television presenter as Mary Parkinson. They had three children: Andrew, a television producer; Nick, a restaurateur; and Michael Jr, who ran his father’s production company. His wife and children survive him.

In 1972 Parkinson featured in the groundbreaking launch issue of Cosmopolitan magazine with the coverline “The most beautiful thing a man can do for a woman”, after revealing that he had had a vasectomy.

The family home was on the riverfront in Bray, Berkshire, where he kept a boat at the bottom of the garden, and friends included the chef Michel Roux Sr, whose famed Waterside Inn is located in the village.

All three children lived within a three-mile radius and he also owned the Royal Oak at Maidenhead, run by Nick, who trained at the Savoy. The gastropub was upmarket enough to earn a Michelin star but was inevitably known to locals as “Parky’s Pub”.

He was born in the pit village of Cudworth, South Yorkshire, in March 1935. His father, John, was a miner who was so passionate about cricket that he wanted to call his son Melbourne because England had won a Test match there.

Although they went to different schools, his best friend in boyhood was Bird, with whom he played cricket and watched the films of Errol Flynn, Humphrey Bogart and Wayne at the local flea pit.

His mother, Freda, whom he called “the engine of my ambition”, encouraged him to read widely and to write, although he hated his years at Barnsley Grammar School, which he dismissed as “a complete waste of time”. He left at the age of 15 with just two O-levels to become a cub reporter on the South Yorkshire Times, attending flower shows and local court hearings on a bicycle until called up for National Service at the age of 19.

It was the making of him: he was selected for an officer training course and became one of the youngest temporary captains in the British Army as a press officer during the Suez operation of 1956.

When he was demobbed he discovered how badly local journalism paid in comparison with the officer class to which he had temporarily belonged. He persevered, however, and joined the Barnsley Chronicle before moving to the Manchester Guardian as a feature writer. The largely Oxbridge staff of the latter paper, which changed its name to The Guardian in 1959, called him “clodpole”, which reinforced his northern chippiness.

Parkinson moved to London to work for the Daily Express and doubled his salary covering the Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial, but he began drinking in the manner of Private Eye’s “Lunchtime O’Booze” character. “I loved those days in Fleet Street. They were disreputable and everyone was pissed but it was vigorous and fun.”

He was rescued by his former Guardian colleague Anthony Howard, who had transferred to ABC television and hired him as a reporter on a weekend magazine programme. Within a year he had moved to Granada TV as a producer and reporter on regional shows before graduating to the networked World in Action.

It was followed by a transfer to the BBC’s Twenty-Four Hours daily current affairs programme, where he learnt much from Michelmore, the main presenter on the show. He covered war in the Congo and the six-day Arab-Israeli conflict before returning to safer ground, first at LWT Television, where he presented Sports Arena, and then back at Granada, to which he returned in 1969 to front the Cinema programme, which featured his first star interview, with Laurence Olivier.

With his craggy good looks, wit and a warm personality attracting admiration across the television industry, it was no surprise that in 1971 Bill Cotton, the head of BBC Light Entertainment, invited him to present a Saturday night chat show based on American models such as The Ed Sullivan Show.

There were objections from Paul Fox, controller of BBC1, who thought that Parkinson - who at this stage of his career had never held down a job for longer than two years - was “idle” and something of a dilettante. But a trial contract was agreed for eight shows transmitted during the “summer lull”, in a late-night slot on Saturdays.

In the end the programme ran for another 11 years and a midweek show was added to the weekend slot, as Parkinson, refusing to clip his fruity regional tones to something more Reithian, joined Harold Wilson and Boycott in a trinity of Britain’s best-known “professional Yorkshiremen”.

He was deeply offended when the BBC’s board of governors accused him of “trivialisation of the airwaves” and manifested his displeasure by accepting an invitation to host an Australian version of his show for six months of the year.

He finally severed all connection with the BBC when he became part of TV-am’s “famous five” consortium, with Frost, Angela Rippon, Anna Ford and Robert Kee, which successfully bid for the new ITV breakfast franchise.

The station went on the air in 1983 but was a disaster. The format was too serious for a mass audience at an early hour and the stress made Parkinson start drinking heavily again. He left in 1984 and his Australian show came to an end the same year.

He turned to radio but his two-year sojourn hosting Desert Island Discs was surprisingly unsuccessful. He dismissed criticism of his tenure as “a rearguard action by the establishment against the perceived desecration of an institution by an outsider” and did not endear himself to the widow of Roy Plomley, the show’s creator, by calling it “a silly little programme”.

Other radio ventures were happier, notably Parkinson’s Sunday Supplement, a mix of chat and music in which he indulged his love of jazz and which ran for a dozen years on BBC Radio 2.

He was pleased to get back into print journalism and was a splendid sports columnist for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph, whether writing about contemporary titans or about the heroes of his youth, such as the Barnsley footballer Skinner Normanton. He published biographies of Best and Ali, and a series of children’s stories, The Woofits. With Tim Rice he launched Pavilion Books, an imprint largely devoted to sport and with a strong cricket catalogue.

He eventually revived the Parkinson show in 1998, first on the BBC and then on ITV, before announcing his retirement in 2007. Parkinson was knighted the following year, having been appointed CBE in 2000.

He still enjoyed the job but was frustrated the second time around that “stars now have all these rules” about what can and cannot be asked. However, he noted his encounter with Nelson Mandela as a late-career highlight.

“Where is the famous BBC interviewer?” Mandela demanded. On being introduced, he warned Parkinson that he was slightly deaf. “I hope, sir, you’ll hear my questions,” he told him. To which Mandela gave his interviewer a benign smile and replied: “I’ll hear the ones I want to answer.”

Parkinson had prostate cancer diagnosed in 2013 and received the news with shock. “I’d never had to consider the possibility I might die,” he said. “I was sublime. I was Superman. I was always going to live for ever.”

The Times