Maldives falls into China’s grip after shunning India

Indian Ocean nation is sinking in a sea of debt after throwing in its lot with Beijing, heightening tensions with India, which fears it is losing its influence among neighbours

Behind the tiny lagoon where small children splash, a span of Chinese-built concrete rears up from the sea, carrying buses and taxis to the Maldives’ international airport.

A short walk away, beside the memorial to those who died in the 2004 tsunami, another bridge, built by Indian labourers, is gradually taking shape.

Pillars looming out of the sea mark where the new bridge will hopscotch across the atoll, linking Male with Thilafushi, the artificial islet that began life as a rubbish dump for the overcrowded capital.

The Maldives is famed as an Indian Ocean paradise, and its economy has been built on its white sands and turquoise waters since it opened up to tourism in the 1970s.

But now the tiny atolls of Asia’s smallest state are lapped by the waves of great power competition as India and China battle for strategic control of the Indian Ocean.

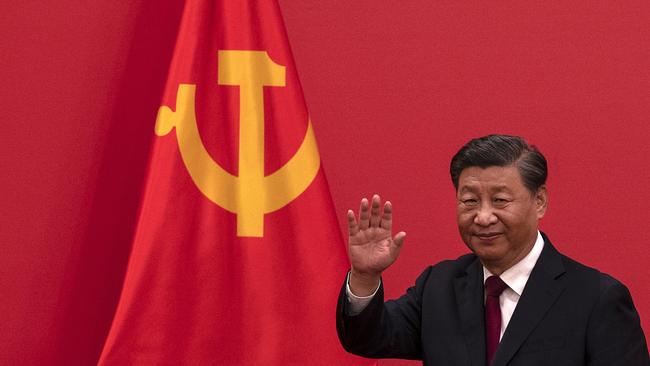

Having seesawed between pro- India and China governments since democracy, the Maldives came down on the side of Beijing this March with a parliamentary landslide fought on an “India out” agenda.

Within weeks, however, the islands were teetering on the brink of economic collapse with soaring debts to China, raising fears the Maldives would soon become Beijing’s latest asset in its battle for regional supremacy.

As fishermen shut down tuna-processing plants to protest at non-payment by the debt-ridden state exporter, ordinary Maldivians contemplated the consequences of their oscillating allegiances to one giant power or another.

“Look, we are almost surrounded by their bridges!” said Abdullah Saeed, a fishermonger at Male Fish Market. “But who are they building them for? Us or them?”

Less than 500 miles off the southern tip of India, the Maldives stayed close to its largest neighbour after winning independence from Britain.

The last British base in the islands closed in 1976. The closed socialist economy and military non-alignment that characterised post-independence India led it to neglect its maritime role.

“Nehru pulled out from economic globalisation and from the imperial defence structures in the name of non-alignment, leaving no room for sea power,” said C Raja Mohan, a professor of strategic studies at the Institute of South Asian Studies in Singapore. “If you are not a trading nation, you are not interested in the sea.”

The Indian Ocean went from “the centre of globalisation under the British Raj” to a backwater, a waterway viewed through the continental divisions of its shorelines in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

India revived its interest in maritime affairs only after economic liberalisation in the Nineties opened it up to trade but its military preoccupations remained with its land borders and territorial disputes with China and Pakistan.

China, meanwhile, was scoping out geostrategic opportunities in the Indian Ocean in a “two-ocean” strategy linking the Pacific to the West.

Washington sounded a warning that under the cover of developing civilian maritime infrastructure, by befriending governments and building ports in developing coastal and island states, Beijing sought to construct a military “string of pearls” across the ocean for its navy’s use. .

In 2014 Beijing brought such projects, which by then included the Sinamale (Chinese-Maldives Friendship) Bridge and the Hambantota port in southern Sri Lanka, together under China’s Belt and Road initiative.

Hambantota, built by China on the ruins of a town wiped out by the 2004 tsunami has become a lesson in the dangers of Chinese largesse.

Although others refused funds over feasibility concerns, China brushed them away and coughed up dollars 1.5 billion, attaching non-financial strings such as intelligence-sharing about naval movements and sweetening the deal with millions paid under the table in black campaign funds for Mahinda Rajapaksa, then Sri Lanka’s president. But Sri Lanka struggled to repay the debt and in 2015 its government was forced to surrender Hambantota to China on a 99-year lease in exchange for debt relief.

Sri Lanka was already more indebted to Beijing than ever. When its economy collapsed in 2022 and the country erupted in protests at the lack of essential supplies, India extended Sri Lanka a lifeline with a dollars 4 billion line of credit, declaring: “Neighbourhood first.”

Underlining the point, Delhi sent a warship loaded with vital medicine. Sri Lanka nonetheless defaulted for the first time and the ruling pro-China Rajapaksa family fled.

Sri Lanka’s multibillion-dollar debts to Beijing continue to hinder its recovery, and concerns linger over Chinese intentions for its ostensibly civilian holdings there.

Among recent visitors to Hambantota was the Yuan Wang 5, one of China’s latest generation of space-tracking ships, which is used to monitor satellite, rocket and intercontinental ballistic missile launches. The arrival caused alarm in India, which fears Chinese encirclement, and prompted Sri Lanka to request that the port call be deferred. China refused, calling it “completely unjustified for certain countries to cite ‘security concerns’ to pressure Sri Lanka”.

China has also wrested control of 43 per cent of Port City Colombo, an expanse of reclaimed land that has extended the Sri Lankan capital by nearly 700 acres into the Indian Ocean. China Harbour Engineering Company, the state-owned contractor behind the Hambantota port and the Maldives’ first intra-island bridge, is building a special economic zone, hailed as a new Hong Kong, on the site.

The view from Colombo’s Galbokka Lighthouse, towards India’s coast, is now obscured by cranes. The cannon that fired Independence Day salutes point emptily at the fences and sentry points surrounding the reclaimed land. Briefly suspended over sovereignty fears after the Rajapaksas first fell from power, the project has resumed.

“Who exactly is going to live there?” asked Asanka Chandrawathi, one of the protesters who stormed the home of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Mahinda’s brother, in 2002. “Look at it, it’s not for ordinary Sri Lankans. We are selling away our country.”

China, however, has a new rival in the commercial port after the US announced in November that it would extend a preferential multimillion-dollar loan to finance a second terminal. The money came from a five-year-old fund set up by the US as a counter to the Belt and Road initiative.

The choice of an Indian contractor, the Adani Group, to construct the terminal speaks to the growing co-operation between India and the US in the battle against Chinese strategic influence. Both countries will be watching closely to see which vessels visit the Chinese terminal next door.

That civilian co-operation mirrors growing naval ties between India and the US in the Indian Ocean.

With the American and British navies stretched countering the Houthi threat to shipping in the Red Sea this year, India sent its largest ever naval deployment to The Gulf of Aden and the east African coast to counter a surge in piracy. The message Delhi intended to convey about its reach was not incidental. Beijing is far ahead of the game in establishing ties and bases in Africa, giving access to the western Indian Ocean, including its large military base in Djibouti next to an American one.

India’s sole foothold is a quietly built jetty and airstrip in the remote Agalega islands of Mauritius on which 50 Indian naval personnel are based.

The US’s only wholly Indian Ocean base is on Diego Garcia, the Chagos island leased from Britain that is at the heart of a sovereignty dispute with Mauritius, from which it was severed. India would dearly love a resolution, if only to see off Chinese rivals.

“The contest for islands is growing in the western Indian Ocean as well as Sri Lanka and Maldives,” Raja Mohan said. “Every speck of land in the Indo-Pacific is being contested, because you have a great new maritime power coming in. It wants access, it wants location, it wants special relationships. India doesn’t have the same resources. That’s why it needs a wider coalition.”

Meanwhile, the last of India’s 80 military personnel left the Maldives in May, fulfilling President Muizzu’s central campaign pledge. But events since have underlined the unintended difficulties of standing up to giant neighbours.

Muizzu’s landslide victory came after a raucous falling out between the Maldives and India after Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, took a trip to promote tourism on the unexploited and distinctly Maldivian-looking Lakshadweep Islands.

The visit was received in Male as an aggressive challenge to the better- established paradise and its tourism sector which, along with tuna fishing, provides the foreign currency needed to finance debt payments.

“What a clown,” tweeted a junior minister in the Maldives’ government as other Muizzi allies chimed in with insults.

Indian politicians and Bollywood stars hit back with nationalistic anger, launching a boycott against the Maldives that made Indian tourism plummet. At that moment Muizzu was in Beijing securing agreements on strategic co-operation.

As in Sri Lanka, successive governments in Male have mirrored their local rivalries with duelling allegiances to India or China, putting the country on a seesaw between the two. After years of switching loyalties, both are inescapably reliant on the massive infrastructure investments of the two giants.

In an effort to calm tensions, Muizzu flew to Delhi for his first visit as president to attend Modi’s swearing-in ceremony on June 9. At a banquet to mark the event, Muizzu was seated on his left with Ranil Wickremesinghe of Sri Lanka on his right.

The foreign debt owed by the Maldives remains vast, with Beijing its largest creditor. Mohamed Nasheed, the Maldives’ first democratically elected leader, warned on his return to politics in 2018 – weeks after the bridge was opened – that the loans with which it was built would lead the country into a Chinese debt trap. Nasheed welcomed a low-cost loan from India as “real help from a friend”.

Nasheed’s warning came true suddenly last month as the Maldives’ new pro-China government stared down the barrel of default.

A plea to Beijing for relief on an estimated debt of dollars 1.5 billion was refused. The cabinet approved painful spending cuts a day after its credit rating was downgraded to junk status and as unpaid bills mounted at the finance ministry. Its debt payments for this year amount to dollars 500 million, more than its entire foreign reserves. By next year, annual payments will exceed dollars 1 billion.

As protests grew, Muizzu declared a new era of austerity. The first cut to public spending announced was the cancellation of annual celebrations on July 26, Independence Day. Fear is now rising in the Maldives over the sovereignty Beijing might seek to exact if the country cannot meet its debts.

Last week China’s most advanced research vessel visited the islands for the third time since the beginning of the year, repeating a pattern that has been seen in Sri Lanka.

Athif Shakoor, an economic commentator, cursed the blindness that had “brought us to these rocky shores”, adding: “We all preferred to believe that lunch was free.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout