Over the past year his Chinese Communist Party’s core achievement – presiding over a path towards broadbased domestic prosperity – found its wheels falling off, illustrated by youth unemployment hitting such levels – well above 20 per cent – that the data was suddenly made a state secret.

The population began shrinking for the first time in six decades, and India took over mid-year as the world’s most populous country. Many in China are now anticipating they will get old before they get rich. This is the reverse of a core party aim. There was also disarray within Xi’s hand-picked leadership team, his foreign and defence ministers both being removed without explanation.

But fortunately for the CCP, in terms of its prospects for global influence, world attention has been distracted by the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. And, in 2024, will again be focused elsewhere, including on elections in major countries, led by the US.

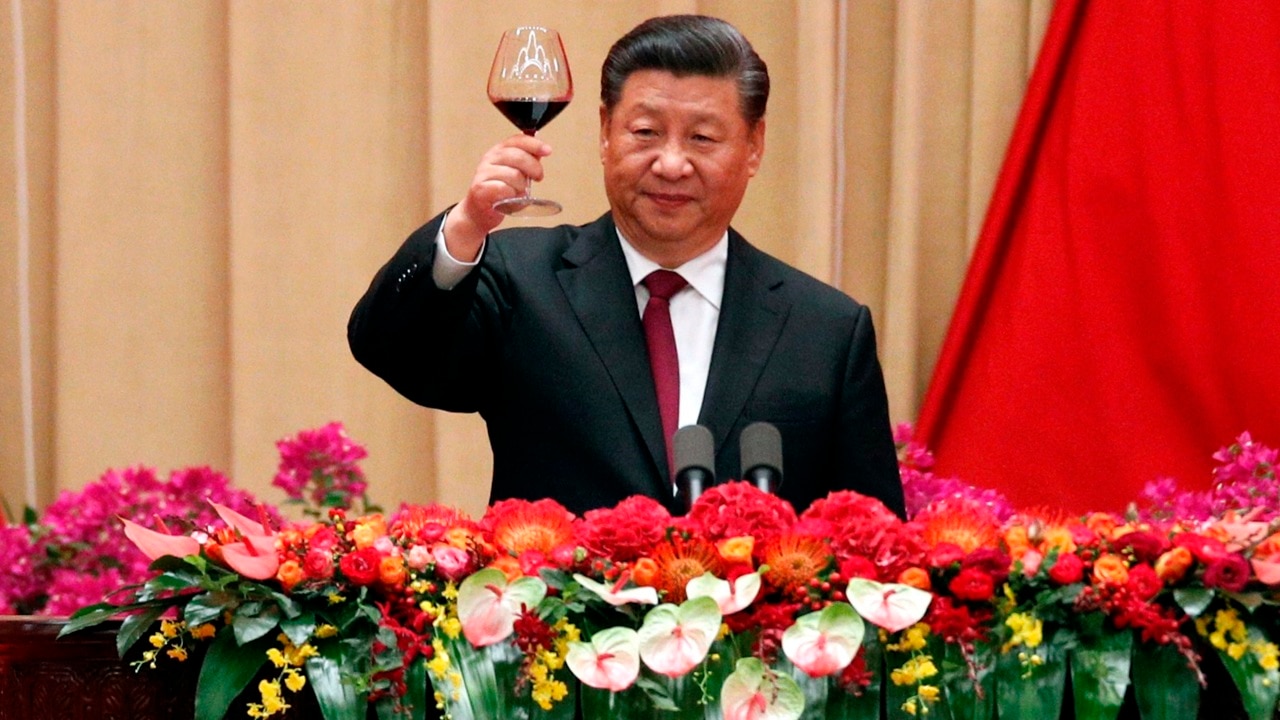

Xi might have raised the beer bottle to toast not only 10 years of his hallmark international scheme, the Belt and Road Initiative, but also its reconstruction as what I dub BRI Mark 2, underlining his restless ambition.

The funds that once flowed in vast quantities – as loans, not grants – through his initiative, largely to the elites of the developing world, have now virtually dried up. But the channels that it opened, are paying off anew, as BRI Mark 2’s flows include Xi’s ideological themes, Chinese businesspeople and corporate investments, and campaigns to counter liberal democracy, especially the Great Enemy, the US.

A handy majority of BRI countries can be relied on to vote Beijing’s way at the UN and other venues. The dark side of the scheme, that continues to shadow it, is debt, which is inevitable because many of the projects were arranged at leader-level. When interest rates were negligible, this mattered less, but now they are on the rise, that’s changed – through the vague way in which the BRI is run, ensures the detail remains blurred.

Beijing deals with such debt overhangs in a variety of ways, according to its own political rather than economic priorities.

In Xi’s China, politics is upstream of everything.

The BRI has also been something of a debt-trap for China’s own giant policy banks, led by China Exim Bank and China Development Bank. The banks were required to deliver on deals often cut at the top political levels, without the usual due diligence.

Their ability to fund greater domestic economic stimulus is being constrained partly by BRI debts, some unlikely ever to be repaid.

It was in 2013 that in Kazakhstan, at the heart of Central Asia, Xi pledged to “build an economic belt along the Silk Road”. Later that year he told the Indonesian parliament of a new “maritime silk road”. He also said China enjoyed a “shared destiny” with Indonesia and the other nine countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations – although ASEAN had been formed 46 years earlier to staunch the spread of communism.

Various iterations followed, eventually becoming what is called in English, oddly, the Belt and Road Initiative, and in Chinese, no less awkwardly, Yi Dai Yi Lu – One Belt, One Road.

Countries are invited to join the BRI by signing a vague memorandum of understanding. Famously, the first sub-national entity in the world to sign up was the state of Victoria, in 2018, led by premier Dan Andrews.

The federal government had decided to join China’s new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, but to sit out the BRI. Three years later, Canberra used the new Foreign Relations Act to cancel Victoria’s commitment.

Internationally, Australia is surrounded by the Belt and Road. Each of the 10 members of ASEAN has joined the BRI, as have all the 10 Pacific island states that have diplomatic relations with Beijing rather than Taipei, as has New Zealand.

In fact, about three-quarters of the countries in the world have signed up, though many have done so because it seems cost-free. Until Beijing starts to call in its “favours”. Western Europe – except Italy, which is now quitting, North America, India and Japan remain substantial holdouts.

The initiative was never cohesively organised. No single Chinese agency took responsibility for it. It aimed to ensure that high-speed-rail, all highways, all technology platforms and regulations, would lead to Beijing as all roads once led to Rome. It also sought to redeploy internationally, China’s formidable development machine, which was already grinding to a halt at home thanks to government-driven overreach, as productivity gains and returns on capital stuttered.

The scheme was never particularly popular at home in China, where living standards remain substantially below those of its East Asian neighbours, and where many believe state funds can be allocated more helpfully. The original vision was to create modern routes – by both land and sea – to channel Chinese products to markets in Europe, and secondarily in India and Southeast Asia. Infrastructure was at its core, with about a trillion US dollars lent, and with Chinese state firms doing much of the building.

This created a superb platform for the weaponisation of China’s economic heft, and Beijing cleverly contrasted it with the conditionality – including anti-corruption measures – that limits lending by Western countries and by multilateral agencies it does not control.

In 2024, Xi will redouble efforts to change or replace the latter, as he pursues his new Global Security, Development and Civilisation Initiatives to complement BRI Mark 1, which provided the initial economic thrust.

Military “modernisation” will also be reinforced, with a further shake-up of generals and the appointment of a new defence minister at the weekend, just as 2023 ends.

The habits of influence coursing through the BRI keep China ahead in the great new global strategic contest for control of critical minerals (especially in Africa) their processing and their chief markets in magnets and batteries.

BRI Mark 2 incorporates a “digital silk road”, modelling authoritarian online control, as well as a new “leadership school” that the CCP built and runs in Tanzania, where the ruling parties of six African countries are sending their cadres for training.

The Belt and Road Initiative is weirdly named. It is running out of money. Vast debt remains. But in 2024 BRI Mark 2 will return other dividends to Xi’s party – meriting that New Year’s Eve toast.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

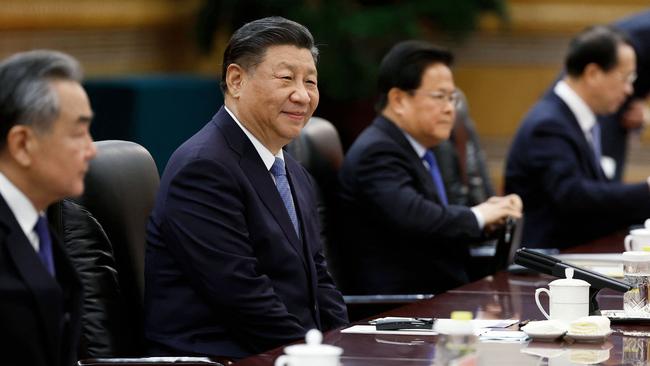

When Xi Jinping eased down a bottle of Yanjing Beer as the New Year ticked over, he’ll have been relieved that 2023 was over, while anticipating international opportunities in the Dragon Year ahead.