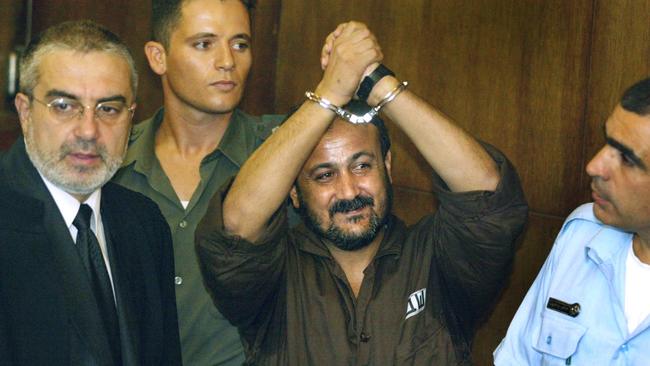

Locked up ‘Mandela’ holds key to ceasefire in Gaza

Hamas has said that top of its list for any exchange of prisoners for Israeli hostages would be Marwan Barghouti.

A proposal to end the war in Gaza that was being studied by Hamas on Monday brings freedom closer for the best-known and most controversial Palestinian political prisoner, the man a recent opinion poll suggested should be the territory’s next president.

Hamas has said that top of its list for any exchange of prisoners for Israeli hostages would be Marwan Barghouti, a veteran West Bank leader whose history symbolises the divide with Israel.

To Israelis he is a terrorist mastermind, serving life in prison after being convicted of five murders. The Israeli government has not said it will agree to his release, nor accepted that it is inevitable, which many negotiators believe.

His supporters say he is the Palestinian Nelson Mandela. Every time that Israel and its supporters around the world demand that Barghouti be described as a terrorist, they say Western leaders once described Mandela as such.

“My father is very popular among Palestinians, and that happened for a reason,” his son Arab Barghouti said at his father’s campaign office in Ramallah.

“My father never made big promises to build roads or schools or the best buildings. He is just someone from the street who made the choice to dedicate his life to the Palestinian cause.”

That struggle has cost him more than two decades of his life. He was arrested and jailed in 2002 for murder, having already served previous shorter terms.

After a statement calling for support for Hamas in the new war was released in his name – though disavowed by his wife – his family says he was brutalised in prison, transferred to solitary confinement and held in the dark with loud music playing for days.

Barghouti’s struggle has earned him the enduring hostility of many average Israelis, who see him as the man who abandoned the peace process to lead the second intifada, or uprising. Starting in 2000, suicide bombers and armed attackers brought havoc to Israel. Bus stops, restaurants and nightclubs were all bombed. Militants fought the Israeli army. More than 3000 Palestinians and 1000 Israelis died.

Barghouti’s role was ambiguous, in part because of his refusal to offer a defence at his trial. He was certainly a top leader of Fatah, the largest secular political faction in the Palestinian territories, and in the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and he led and justified both intifadas.

The first involved much less violence, and largely comprised strikes and protests. Backers of Fatah and Hamas say the second, armed intifada was necessary because of the collapse of the peace process and what they say were provocative acts by the Israeli right.

Israel held all the Palestinian leaders, including Barghouti, responsible for the hundreds of Israeli civilian deaths, and accused Barghouti of personally masterminding some of them.

His chief of staff, Ahmed Ghuneim, said Barghouti, 64, had argued against targeting civilians, but that other factions and individual fighters had acted independently. “We were fighting the Israeli military, which was attacking our country, attacking our villages, killing our people,” Ghuneim said.

As a leader of Fatah, Barghouti represents the traditional and secular wing of the Palestinian cause, often termed “moderate” in comparison with the Islamic militancy of Hamas and its ally in the Gaza war, Islamic Jihad.

He accepted the peace process and Oslo Accords negotiated by Yasser Arafat, leader of the PLO, and Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister. That means he has accepted the existence of the Israeli state, and is in line with Western calls for a two-state solution.

However, his role in the second intifada as leader of Fatah’s military wing has granted him legitimacy with factions at war with Israel. His long stay in prison means he has avoided the stigma attached to his Fatah colleagues in the West Bank, including Mahmoud Abbas, President of the Palestinian Authority, who is accused of corruption.

An opinion poll conducted among Palestinians in December showed that in a three-way ballot for the presidency, Barghouti would receive 47 per cent of the vote, to 43 per cent for Ismail Haniyeh, the leader of Hamas, whose standing has risen since the war began. Abbas would receive 7 per cent.

Reports on Sunday night indicated that Hamas was on the verge of responding to a ceasefire offer that would involve a gradual exchange of prisoners for hostages over a period of six weeks.

The US wants a deal to be followed by negotiations for a new government in Gaza, preferably led by a unified Palestinian Authority under changed leadership, with Hamas sidelined.

There is no clear mechanism for Abbas to be ousted, but few diplomats believe he can bring about the change demanded by Israel, the Palestinians or negotiators. Israel will not want Barghouti as a replacement. But his son said it was in Israel’s best interest to accept a settlement before world opinion turned against it, and with a leader who accepted its existence.

“My father values peace,” he said. “He never demanded the destruction of any state, including Israel. He always said he wanted people to live in dignity, and for the Palestinian people not to be an exception.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout