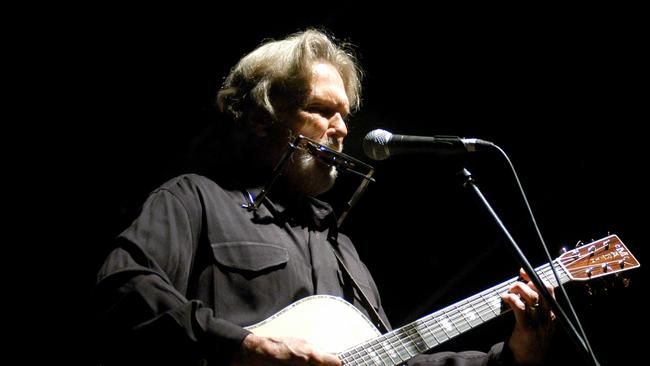

Kris Kristofferson, country singer and Hollywood star, dead at 88

He was known as the hyper-literate hillbilly who made his own rules, with his songs transforming the genre in the Seventies.

Kris Kristofferson, singer, songwriter and actor, was born on June 22, 1936. He died on September 28, 2024, aged 88

As well he knew, Kris Kristofferson could have been describing himself when he wrote the lyrics for Pilgrim, Chapter 33: “A walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction, taking every wrong direction on his lonely way back home.”

He wrote hits for other artists but was ignored when he tried to record them himself; his brief spells of critical acclaim were generally followed by condemnation; he had a knack for acting in poor films with bad scripts and then defending them to the hilt anyway.

In the 1990s he dismissed what remained of his musical following by embracing left-leaning causes. Too intellectual to be a cowboy and too self-conscious to be a proper star, the only country and western cliche he might truly have lived up to was indulging in the twin demons of drink and drugs.

Yet his songs would transform the genre of country in the Seventies, much in the same way Bob Dylan had changed folk rock a decade before. In the 1970s the charts were flooded with such tepid tunes as Okie from Muskogee, with lyrics such as “We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee, and we don’t take our trips on LSD”. Kristofferson was seen as the hyper-literate hillbilly whose diet of Shakespeare and Salinger from his Oxford degree intellectualised the genre. And he still ambled around in cowboy garb with a flask of whisky (apparently) jammed in his boot. “Kris made his own rules,” said his fellow country star Willie Nelson, “did it his own way.”

Kristofferson, a modest man who eased his well-documented stage nerves with self-deprecating jokes, never saw himself as blazing a trail. His songs, he said, simply carved new ways of reflecting the changing times. “Writing comes as natural as a bird to me, always did,” he said. “It’s the way singer-songwriters make sense of our lives.”

Born in Brownsville, Texas, in 1936, Kristoffer Kristofferson was the son of Mary Ann (nee Ashbrook) and Lars Henry Kristofferson, an army major-general who had fought in the Second World War and in Korea. He expected his son to follow a similar path and pushed him hard academically.

Aged 11, the family moved to San Francisco and Kristofferson studied creative literature at Pomona College in Claremont, California, later transferring to Merton College, Oxford, to study English literature on a Rhodes scholarship. There he got a boxing blue, excelled at rugby and became enraptured by poetry. He was asked to leave one course after a raging argument with his tutor over William Blake.

After graduating he remained in England, performing as Kris Carson when he was signed by Tommy Steele’s promoter. He got a deal with the Top Rank label, but nothing came of it. Upon his return to the US he joined the army, volunteering in Vietnam, and quickly married. He achieved the rank of captain but, dissatisfied, he walked out of West Point to pursue his dream of being a songwriter.

Although his father accepted his decision, his mother never entirely forgave him for throwing his career away “to become a bum” and they disowned him. He was already drinking heavily and he had two children, one with a defective oesophagus — which meant he needed to find $100,000 for medical bills. He moved to the coast and took a job as a part-time helicopter pilot serving oilrigs in The Gulf of Mexico, but was sacked after passing out drunk at the controls.

He returned to Nashville, lived in a slum and in 1965 got a job working as a janitor in recording studios. In 1960 he had married his high school sweetheart, Fran Beer, but he drank heavily to forget his mediocre achievements and they divorced eight years later. He was briefly put in jail for failure to pay child support. “I felt the freedom then of nothing left to lose,” he recalled. “I was a failure, and it was a very liberating thing.”

He had persuaded his hero, Johnny Cash, to take some of his songs but they were never recorded. Emboldened by his dire circumstances, he landed a helicopter in Cash’s garden with a beer in one hand and a tape in the other, although elements of the story were somewhat exaggerated. Impressed, Cash agreed to record Kristofferson’s Sunday Morning Coming Down. It was a hit, voted song of the year by the Country Music Association in 1970.

He joined the army, but was still pursuing his interest in music and songwriting. He was offered a teaching job at West Point but decided instead to head to Nashville, where he began to submit songs for others to record.

He finally signed his own record deal and put out a first album in 1970. He would earn success both with his own voice and by providing tunes for other hitmakers.

Cash took “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” to the top of the charts, and Ray Price did the same with “For the Good Times.” “Me and Bobby McGee” became a posthumous hit for Janis Joplin, who once dated Kristofferson.

Its great rival, the Academy of Country Music, chose another of Kristofferson’s songs — For The Good Times, recorded by Ray Price — as its own song of the year. This was the only time in the history of country music that an artist has taken both awards with different songs, and the tune that was to become his signature, Me and Bobby McGee, was recorded first by Roger Miller, then by his friend Janis Joplin. It was her only No 1, and she died soon after recording it.

Kristofferson found success on his own terms far more difficult. He never made it in Nashville but signed to Monument records in California and recorded his debut album, Kristofferson, featuring the hit songs and several new ones, but it proved a dud. It helped his bank balance, but not his ego, when his compositions were recorded successfully by Waylon Jennings, Bobby Bare, Sammi Smith, Patti Page, OC Smith and others.

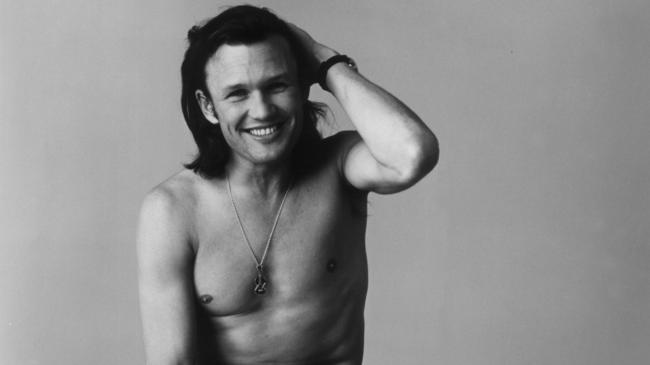

His second album, The Silver Tongued Devil and I — a paean to wasted behaviour and meaningless sex — was a success, at last establishing Kristofferson as a recording talent. “When he ambles onstage he is a road-weary troubadour come to tell about what he’s just been through,” went a New York Times review in 1970. “A wiry, 5ft 11in frame hunched over a 12-string guitar, deep blue eyes trying to remember exactly how it was, raspy voice half talking and half singing the lyrics; yellowed fingers reaching for a beer and another Bull Durham (three packs a day) during instrumental breaks.”

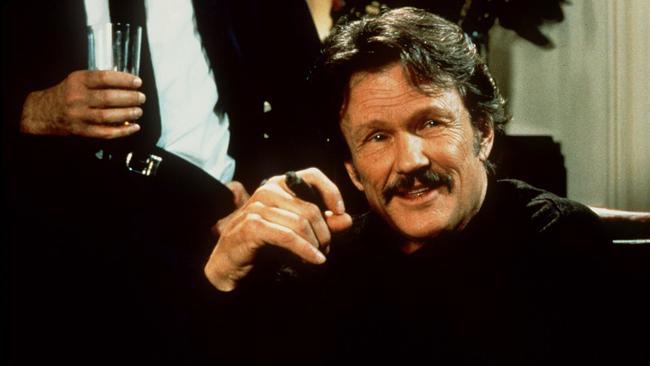

Asked to provide original music for Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie in 1971, Kristofferson found himself playing a bit part as a minstrel wrangler, and the next year was persuaded by Harry Dean Stanton to play the lead in Cisco Pike, a downbeat, sadly humorous tale of a corrupted former rock star. The film has garnered far more appreciation in retrospect than it did at the time, and it is now considered a classic of hippy culture. Kristofferson disliked it, aware of his limitations: “I had two expressions in that movie,” he said, “vacant and confused.”

He had never wanted nor intended to be an actor, but things were not going smoothly in music. He was booed off stage at the Isle of Wight Festival (the audience missed the irony of Blame It on the Stones), while Sam Peckinpah saw in him the hellraiser he needed to play the outlaw in his next picture, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). Kristofferson appeared in Peckinpah’s Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974) and Convoy (1978). Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) showed that he could be just as effective when being tender and hurt — particularly when the mouthy son Tommy rejects his “shit-kicking music”.

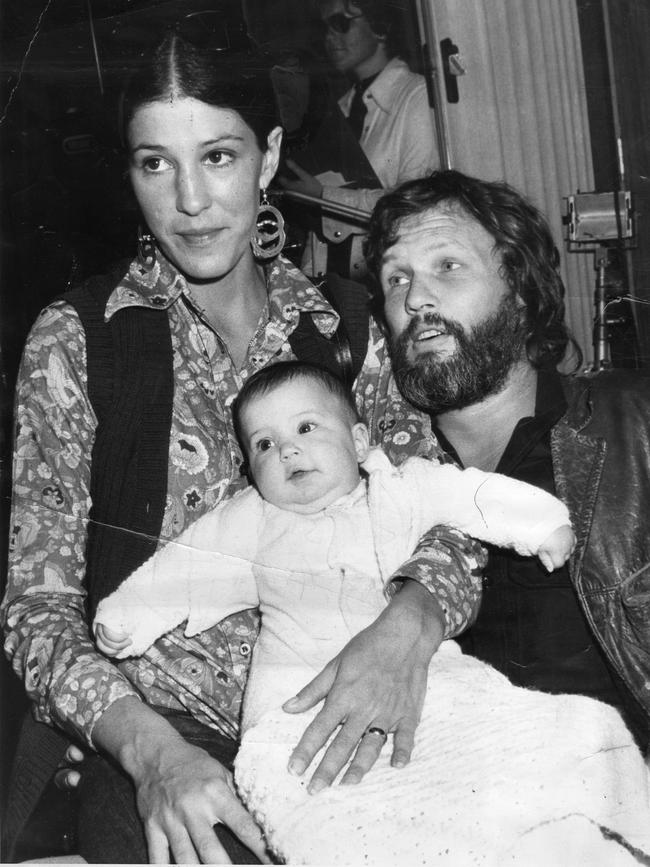

Dogged by drink, he helped to promote the release of the rather turgid The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea (1976) by appearing naked in Playboy with his co-star Sarah Miles. The pictures almost ended his marriage to his second wife Rita Coolidge, a singer with whom he recorded four albums, although he maintained having no recollection of posing for them.

His turnaround came while playing a booze-sozzled has been rocker in the remake of A Star is Born (1976). Although the film, made to the requirements of Barbra Streisand, was not his best, he won a golden globe and an epiphany: seeing his own death from drink in the picture made Kristofferson drop his bottle-and-a-half-a-day bourbon habit.

A decade of hard-living and womanising had, however, broken up his marriage to Coolidge in 1980 and he became estranged from his children. The divorce also coincided with the death of his agent, his manager, the bankruptcy of his record company and the release of Heaven’s Gate, which, according to one reporter, was “the metaphor for utter disaster in Hollywood”.

“That year was not good for me, or the Shah of Iran,” he later joked. A multimillion-dollar anti-western, Heaven’s Gate almost bankrupted United Artists and destroyed the career of the Deer Hunter director Michael Cimino. It reduced Kristofferson thereafter to bit-part roles, and he effectively vanished, turning up only in the TV series Amerika, about the US under Soviet occupation. It was one of his few real embarrassments in later life.

In the 1990s he was prepared to play almost anywhere, once flying to London just to play one night at the Mean Fiddler in Harlesden. He joined forces with Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash to form The Highwaymen, a country supergroup that enjoyed great success. He no longer sought acclaim in his solo work, preferring to do as he pleased: Polygram dropped him after the release of the album Third World Warrior, saying its peacenik anthems, decrying the American bully, were “unmarketable” to a conservative country audience.

Kristofferson’s opposition to The Gulf War in 1991 had already led to his concerts being picketed. By now indifferent, he expressed support for causes as diverse as Farm Aid and Artists Against Racism and expressed his admiration for Vanessa Redgrave when he visited Britain. He returned in a small way to movie acclaim with the Merchant Ivory film A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries (1998) and his acting still moved the most respected of directors. “There is truth when he speaks,” said Scorsese. “You sense that he is genuine. He has that big, iconic American face — with the soul of a poet.”

With his shaggy hair and unkempt, silver-flecked beard, Kristofferson still had the aesthetic of a street busker in later life. He moved to a remote house on the island of Maui with his third wife Lisa Meyers, who became his manager. She survives him along with eight children: Tracy and Kris from his first marriage; from his second, Casey, and from his final marriage Jesse, Jody, Johnny, Kelly Marie and Blake.

Kristofferson’s compositions have been performed by more than 500 artists, and his impact on American music was far greater than his fame or his rewards suggest. His songs were arguably never true to the country style when he performed them himself, and he acknowledged that his voice was too thin and ragged. Perhaps he was too individual even for a cowboy culture that exults the outlaw. Yet he was never ungrateful, once telling a journalist: “I don’t know how I’ve got what I’ve got after the life I’ve led.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout