Janis Joplin’s letters reveal the girl who became a 1960s superstar

Her sudden fame and wild hedonism led to a tragic early death. But Janis Joplin’s letters reveal a different side to the singer.

When Janis Joplin toured America in 1970, just a few months before her death at the age of 27, a Rolling Stone reporter who was travelling with her took note of the contents of her handbag.

Inside were two movie-ticket stubs, a packet of cigarettes, an antique cigarette holder, several motel and hotel-room keys, a box of Kleenex, various make-up cases, guitar picks, a bottle of Southern Comfort (empty), a hip flask, cassettes of Otis Redding and Johnny Cash, aspirin, a corkscrew, an alarm clock, a copy of Time magazine, and two hefty books — Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel and Nancy Milford’s biography of Zelda Fitzgerald.

The accoutrements of the performer as gypsy: her vanities and foibles, her taste for music, and for alcohol, and — not so predictable, perhaps — her passion for literature. Joplin had fallen in love with the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald as a young girl, and was deeply enamoured with the story of Scott and Zelda — as she put it, “that all-out, full-tilt, hellbent way of living”.

We think we know about Janis Joplin — the rock singer who went full throttle in her performances and her life; the misunderstood girl who escaped the stifling conservatism of small-town America to find freedom in the hippie milieu of San Francisco; a walking morality tale of 1960s hedonism; and a card-carrying member of the 27 Club, along with Jim Morrison, Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse, all of whom died, tragically, at that age. But as a new documentary shows, Joplin’s life was more complicated than that. Janis: Little Girl Blue is the first documentary about the singer to have access to the Joplin family’s correspondence. It draws on letters charting the course of her life, from her troubled childhood in Texas to international fame, along with archive footage and interviews with friends and family, to present a deeply affecting portrait. Little Girl Blue has been seven years in the making, since American documentary maker Amy Berg first learnt that Joplin’s family were meeting with filmmakers with a view to making their archive available. Negotiating for various rights to music and archive material proved a protracted process. “There was a point where it looked like I might not be able to use the letters at all,” Berg says. “But I wouldn’t have made the film without them.”

“Things have their own pace,” Joplin’s sister, Laura, says. “We were talking to people off and on but things didn’t work. I think now is the right time to be reflecting, and it allows us to look with a different heart and a different sense of perspective — and getting Amy involved allowed this to be the kind of film that I really wanted.”

Joplin was born in the Texas oil town of Port Arthur. Her father was a mechanical engineer for Texaco; her mother had been a professional concert singer until illness halted her career. The eldest of three children — she had a brother and sister — Joplin was always something of an outsider. Overweight, with skin problems, she was never going to conform to the prom-queen ideal. Port Arthur was a working town, and Joplin’s parents, Laura says, were “much more intellectually sophisticated” than most. The children were encouraged to read “quality books” — and to read constantly. “Our parents gave us the perspective to think, to try to understand and debate issues at the dinner table.”

Joplin, as one childhood friend remembers in Little Girl Blue, “couldn’t figure out how to make herself like everybody else”. She fell in with what passed in Port Arthur for a bohemian crowd, discovered beat literature and jazz, and, in a town that had an active chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, had the temerity to speak out against racial segregation. “That made her a target,” Laura says. “There were a lot of rednecks in our high school, and it just seemed to escalate. She wasn’t that outrageous by today’s standards. Her skirts were an inch shorter; she didn’t wear bobby socks with her shoes; her hair was a little different in style. But conformity in the 1950s was extreme, and in the South it was even more extreme. That sort of harassment in school is devastating. It became very traumatic for her.”

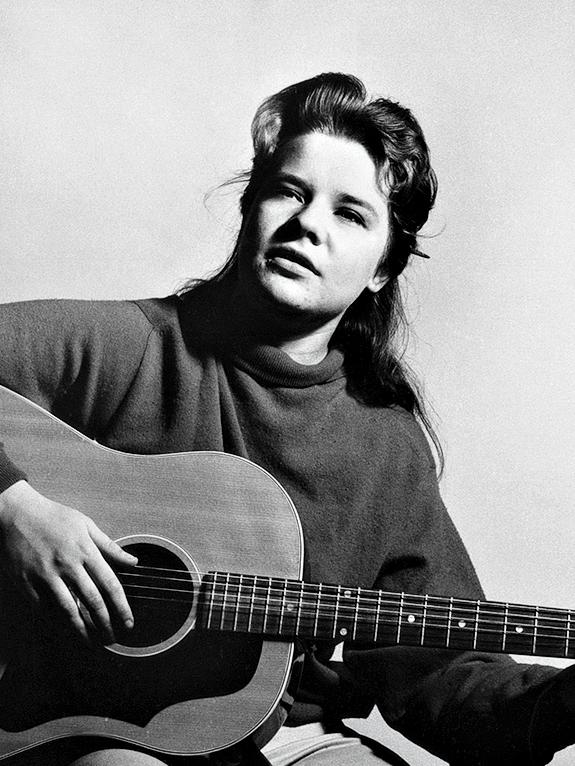

Joplin would put it more succinctly: “I was a misfit. I read, I painted, I didn’t hate niggers.” Discovering the music of Lead Belly and Odetta, she bought an autoharp and began singing. For a few years she drifted, into college and out. In 1962 she moved to Austin and enrolled in a fine-arts program at the University of Texas, singing in folk clubs at night.

The campus newspaper, The Daily Texan, published a profile of her with the headline “She Dares To Be Different”. It began, “She goes barefooted when she feels like it, wears Levi’s to class because they’re more comfortable, and carries her autoharp with her everywhere she goes … Her name is Janis Joplin.” Shortly after, a fraternity voted her “ugliest man” on campus. “It crushed her,” Berg says. In 1963, she left college and hitchhiked to San Francisco with a friend, Chet Helms. She hung out in the bars of North Beach and performed in folk clubs. She was arrested for shoplifting, got beaten up in a street fight, dealt drugs and developed a heavy habit herself, shooting up methedrine.

Looking back, she would later describe herself as “a plain overweight chick. I wanted something more than bowling alleys and drive-ins. I’d’ve f…ed anything, taken anything. I did. I’d take it, suck it, lick it, smoke it, shoot it, drop it, fall in love with it.” She wrote home to her parents, “I want to be happy so f…ing bad.”

Eventually her health became critical enough for friends to raise the money to send her back to Port Arthur. In an attempt to straighten out, she enrolled in a sociology course at Lamar University, in nearby Beaumont, avoided drugs and alcohol and adopted a beehive hairdo.

Then, in May 1966, Helms sent word that she should come back to San Francisco and join a band he was managing, Big Brother & The Holding Company. It would give her focus for the first time in her life. “All my life I just wanted to be a beatnik,” she told the journalist David Dalton. “Meet all the heavies, get stoned, get laid, have a good time. That’s all I ever wanted. Except I knew I had a good voice and I could always get a couple of beers off of it. All of a sudden someone threw me in this rock’n’roll band … And I decided then and there that that was it. I never wanted to do anything else.”

“She had been an outcast, and San Francisco welcomed outcasts,” John Cooke, Joplin’s road manager from 1967 until her death, tells me. “It was a place that questioned and rejected all the platitudes of the dominant culture that she’d grown up with — about dope, about how to behave. It was the first place where she was welcomed for what she was, and not tried to be made into a proper 1950s teen.”

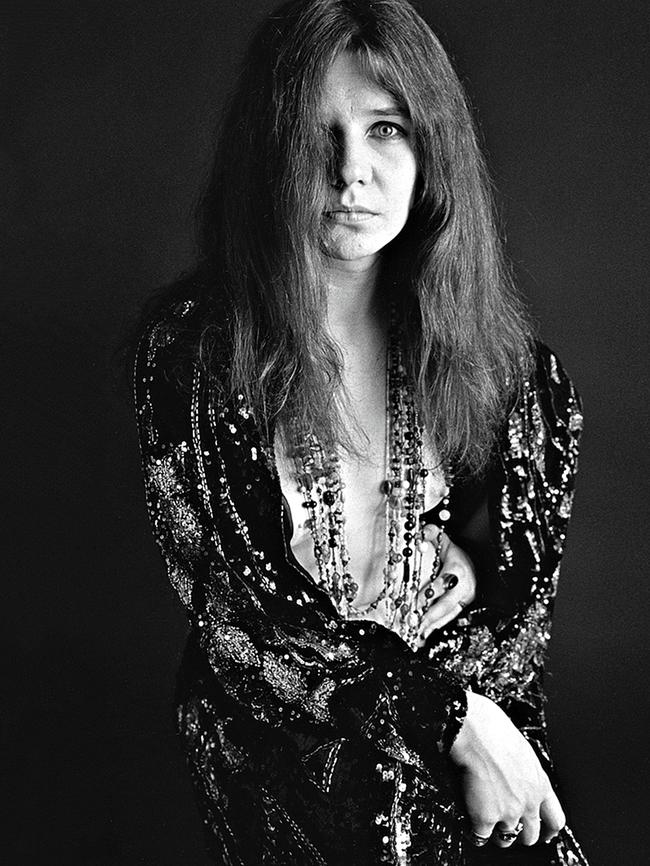

In 1967 Big Brother & The Holding Company released their first album and performed at the Monterey Pop Festival. The first great gathering of the hippie tribes, and the prelude to the “summer of love”, the festival introduced three great talents to the wider American public: Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Otis Redding. In three years, all would be dead. To watch Joplin on stage — the shimmering, bell-bottomed pants suit, flying hair and ravaged countenance — is to witness less a performance than an electrifying act of possession. Her uncorked emotion and freewheeling raps with the audience were modelled on the blues and R&B singers she loved, but she had the gift of making everything she sang her own, and true to her own experience. “Mostly what I’m trying to do in the whole world is not bullshit myself,” she said.

“She used to say, ‘I put up with 23 hours of the day just for that one hour on stage, because I get to get up there and feel,” Cooke recalls. “That’s what she lived for.”

In 1968, Big Brother’s second album, Cheap Thrills, went to the top of the US charts, selling one million copies and making Joplin a star — “the most staggering leading woman in rock”, according to Vogue, which anointed her with a portrait by Richard Avedon. She had become the poster girl for counterculture hedonism: a hard-drinking man’s woman with a raucous laugh and a longshoreman’s tongue. Watching Little Girl Blue, one is reminded of just how challenging she must have seemed to conservative 1960s America.

Joplin fed the mythology of herself as the rebel. She told friends her parents had thrown her out at 14. They hadn’t. But her letters home suggest that for all the shibboleths about parents being the enemy, she craved a close connection with her family. “Now about Christmas,” she writes in one letter in 1966, shortly after arriving in San Francisco. “The only thing that I can think of that I want is a good, all round cookbook, Betty Crocker or any good one. Also could use a couple of pairs of tights — if they still sell them … And what is this $20 check for? I think I can afford to buy everyone presents.” “Haven’t heard any word from you yet,” she writes later, “but presume we’re still speaking.” She goes on to say that “everyone seems very taken w/ my singing” and, “Don’t worry … haven’t lost or gained any weight and my head’s still fine.”

“She wrote lengthy letters, and after she made enough money she made lots of telephone calls,” Laura says. But for her parents the transformation in their daughter was clearly bemusing. Laura recalls, when Joplin first became famous, the family driving to San Francisco to watch her perform. “I remember one of my parents telling the other, ‘Dear, I don’t think we’re going to have much influence anymore.’ But I think she felt very supported and loved by the family. She didn’t expect her parents to become hippies, but they still had a strong bond. We all did. They wanted more than anything for her to be a success.”

Joplin has come to be regarded as something of a torchbearer for feminism — a strong woman who let nothing stand in her way. But she was never adopted by the feminist movement of the day; nor did she adopt it herself. She certainly didn’t subscribe to the radical-feminist orthodoxies of the superfluousness of men. She fell in love at a heartbeat; her sexual appetites are best described as ravenous (she had female as well as male lovers), her judgment frequently awry.

The closest she came to marriage, towards the end of her life, was to a junkie who became a drug dealer and pimp, and later served time for armed robbery. “I don’t think she ever identified with the feminist movement per se,” Berg says. “She didn’t wear a bra, she didn’t shave her armpits; she gave men and women, black and white, equal treatment across the board, but she didn’t identify with labels. She just embraced the idea that women can do whatever they want to do and that she was going to follow her own path. There was a suggestion that the feminists were mad at her for being too sexual, and she was like, ‘What are they talking about? I’m representing everything they want.’ She loved men, she loved women, she wanted to be embraced by all — she wanted to be loved. She did what felt right for her. What I love about her is that she had such great tastes and she followed her instincts — musically, socially and in fashion, everything.”

But as her star rose, the ground began to shift under her. With a new manager, Albert Grossman (who also managed Bob Dylan) in late 1968 she left Big Brother and struck out on her own. Grossman recruited a group of musicians for hire, who Joplin christened the Kozmic Blues Band, to accompany her. But without the familial support of Big Brother, and with all the pressure now on her, Joplin turned to heroin to supplement her heavy drinking. “I might be going too fast,” she told a New York Times reporter in March 1969. “That’s what a doctor said … I don’t go back to him anymore. Man, I’d rather have 10 years of super-hyper-most than live to be 70 by sitting in some goddamn chair watching TV.”

That month, her friend Linda Gravenites found her collapsed at home in San Francisco, purple-faced from an overdose, and walked her around the streets until the early hours of the morning, almost certainly saving her life.

In January 1970, she parted company with the Kozmic Blues Band. She wrote a letter home saying she had “managed to pass my 27th birthday without really feeling it”, and reflecting on her success and fame. “After you reach a certain level of talent, and quite a few have that talent, the deciding factor is ambition, or as I see it how much you really need — need to be loved, to be proud of yourself … I guess that’s what ambition is; it’s not all a depraved quest for position and money, maybe it’s for love. Lots of love.”

In an attempt to curb her drinking and heroin use, she travelled to Rio de Janeiro with Gravenites for the carnival. She left her heroin stash with her friend and sometime lover Peggy Caserta. In Rio, Joplin met an American, David Niehaus, who had given up his job as a schoolteacher to backpack around the world. Niehaus had no idea who Joplin was; he simply enjoyed her company. They became lovers and travelled through Brazil before returning to America together. “He saw Janis the woman, not the rock star,” Berg says. “And that was one of her big challenges, the fact that people she met would want to sleep with her because she was Janis Joplin, but they didn’t want anything beyond that. That was her thing — young, pretty boys and groupies — and then she meets this guy who sees her as a woman, and that was profound for her. He wasn’t a hippie, he was a world traveller, a mountain man in a way, and he was strong enough to handle her.”

Niehaus eventually left, unable to countenance Joplin’s sporadic heroin use. “She spoke of him as her lost love,” Cooke says. “And she still hoped he would come back after she got clean.” In the summer of 1970 she wrote to Niehaus to tell him that she had been clean for four months and was back on the road with a new group, the Full Tilt Boogie Band. “She was a changed woman,” Cooke says. “She had a band that worshipped her, she had been straight for a few months and she was feeling in charge of herself. It was just like, ‘Here I am, man — I’m back’, and she was having so much fun.” She had also started working on an album with a new producer, Paul Rothschild. For all her talent and fame, though, Joplin did not see much future for herself as a singer. “She gave so much to singing that her expectation was that she’d blow her voice out,” Cooke says. “She said, ‘When that happens, I’ll buy a bar in Marin County — ‘come to Janis’s’.”

But Joplin evidently still nurtured a fatalistic sense of her future. On September 18, Hendrix died. “Goddammit,” Joplin told friends, “he beat me to it.” Two weeks later, on October 3, following a recording session in Los Angeles, Joplin returned to the Landmark motel, where she was staying. The following day Cooke found her dead in her room from a heroin overdose. “She had taken so much pride in what she had achieved from quitting, putting her new band together and going out on tour,” Cooke says. “But she had that addictive gene. She was feeling so strong, and then the little demon says, ‘You can handle this, why not give yourself a little reward?’ If that one thing had been different, she might still be here. That’s why it’s a tragedy.”

A tragedy given added poignancy by Little Girl Blue’s concluding revelation that on the morning after Joplin’s death a telegram was found at the Landmark’s front desk from Niehaus, telling her he would meet her in Kathmandu, and signed, “Love you Mama, more than you know…” “You do wonder, if she hadn’t died, whether she would have written a letter back: ‘I’m coming in a couple of weeks’,” Berg says. “Maybe that would have changed things. But it was her destiny.”

© The Telegraph