Institutional cowardice is killing free speech

Albert Wan is shutting his business next month. Bleak House Books, just off the Choi Hung Road in Hong Kong, is one of the city’s last English language bookshops. “There comes a point,” he said on the radio this week, “when you can’t take any more.”

On his blog Wan wrote that he had wanted to stock political titles among all the other books, but there was ever “more pressure to self-censor than before”. He couldn’t bear the idea of finding himself second-guessing the authoritarians in Beijing and doing their dirty work. So he’s cancelling himself.

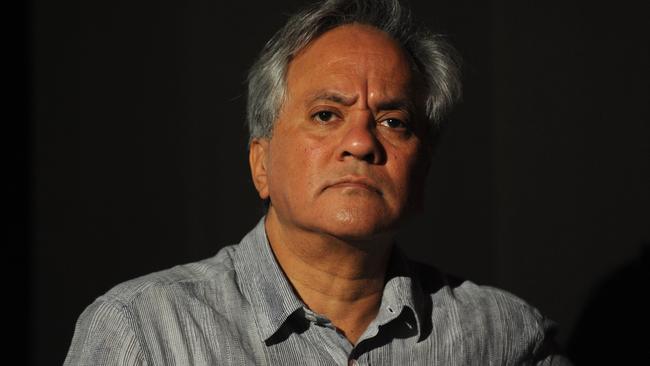

Coincidentally I was at the Index on Censorship awards on Sunday where the great sculptor Sir Anish Kapoor made a short speech on the dangers of self-censorship. It was, he said, the most insidious kind of repression since it co-opted the victim into the crime. And he felt that the pressure to police one’s own artistic expression or one’s speech was growing.

Most of us at some time bite our tongues out of courtesy, fear of causing hurt, or worry that we will be thought dim.

But that’s not what we’re talking about here. Which is the self-censorship that arises from a fear of reprisal. Of repercussions. Of losing our livelihoods, disadvantaging our families, or of not succeeding.

Authoritarian regimes ban dissent outright and imprison offenders. The chances are that Albert Wan would have ended up deported or in prison at some point in the future. “Illiberal democracies” increasingly use ingenious forms of legal harassment to ensure the penalty for dissident expression is high.

In mature democracies, however, there is a different kind of struggle. When I was young there was still a Lord Chamberlain acting as theatre censor and laws against outraging public decency that could be liberally applied. The struggles for free expression centred on allowing works regarded by the establishment and Middle Britain as blasphemous or filthy. And one by one, Lady Chatterley onwards, the walls fell. By the time Jerry Springer: the Opera appeared on the BBC 16 years ago, the battle was won. Heaven knew, anything went.

Yet this week MPs were debating in committee the passage of the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill, which establishes a legal requirement for universities and colleges in England to (in the government’s words) “defend free speech and stamp out unlawful silencing”.

I’m very enthusiastic about free speech and dislike its abrogation.

But I couldn’t help noticing that a lot of the evidence wasn’t about the no-platforming of speakers or the mistreatment of dissenting academics. It was about something far more inchoate – the “chilling effect” of what was described as a liberal monoculture. One principal witness argued that the fact that only 10 per cent of academics voted for Brexit was one indication of an unhealthy lack of opinion diversity and that this absence of diversity fostered intolerance. Within this culture people were afraid to air contrary opinions and thus self-censored.

I think this is clearly true. There is indeed a paradox in which students may well leave one monoculture (usually a racial or religious one) to encounter a variety of kinds of other people but, in effect, one dominant world view. Other monocultures of course are available. In the first episode of Clarkson’s Farm on Amazon Prime the retired boy racer attends an agricultural auction in Oxfordshire. There was plenty of diversity, he told the camera, because present was “every kind of 60-year-old white man you could possibly imagine”.

To what extent are those monocultures atmospherically or institutionally repressive? In other words, just how brave would you have to be to swim against the tide?

Some of what I heard at the committee was snowflakery, and it afflicts both left and right. What would a serially arrested, serially harassed dissident Russian performer make of these people’s plight? But some of it isn’t just fluff. And here we’re talking about instances where the penalties for speaking freely can be real and the main result is likely to be a self-guided reticence to express what you think to be true.

The common link in these situations is not the “monoculture” but institutional cowardice. The terrible truth is that the more exalted the corporation, the gallery, the college, the more feeble and subject to panic is its top management.

When presented with a strident argument by people claiming to represent polities that the bosses don’t quite connect with, they are increasingly – in this fallen social media world – likely to capitulate. Consider, for example, the way British institutions outsourced their equality training to the pressure group Stonewall.

On Broadway, reopening theatres have struck a deal with black activists. Most of the group’s demands were reasonable, or at least could be enacted without harm. Renaming some theatres after someone other than a dead white man won’t kill anybody. Trying harder to get better representation in theatre and production management is fine, too. But also agreed was the use of “racial sensitivity coaches” to “flag” problems at every stage of the production of anything deemed sensitive.

That is a recipe for self-censorship. It inserts a busybody between the creator and the realisation. In no time writers and directors would be trying to second-guess the sensitivity coach. Theatre, like visual art, should be as nearly as possible the voice of the creator talking to the listener. Yet those who should protect it are instead surrendering it.

The same is happening in galleries. Look at the postponed retrospective of the (white) American artist Philip Guston last year. One of Guston’s themes was a depiction of a banal Ku Klux Klan figure, clearly intended to show how commonplace racism was in America. Even so, in the wake of the George Floyd murder a decision was made by the galleries concerned (and backed by the Tate in Britain) to rethink the exhibition – not because their own judgment required it but because activists and some of their staff had advised it. Put simply, it chimed with a lobby that says there are some things white people can’t talk, write or make art about. And those in charge whose role in life should be to resist such demands are instead giving in to them. They settle for a dishonourable peace. As long as they still run things.

The solution is not unenforceable laws in our universities (the first case brought by a campus Holocaust-denier should prove that). The transformative answer is a robust agreement that freedom of expression and speech – and a genuine and pluralist commitment to them – are the essential underpinnings of a creative and dynamic society.

The Times