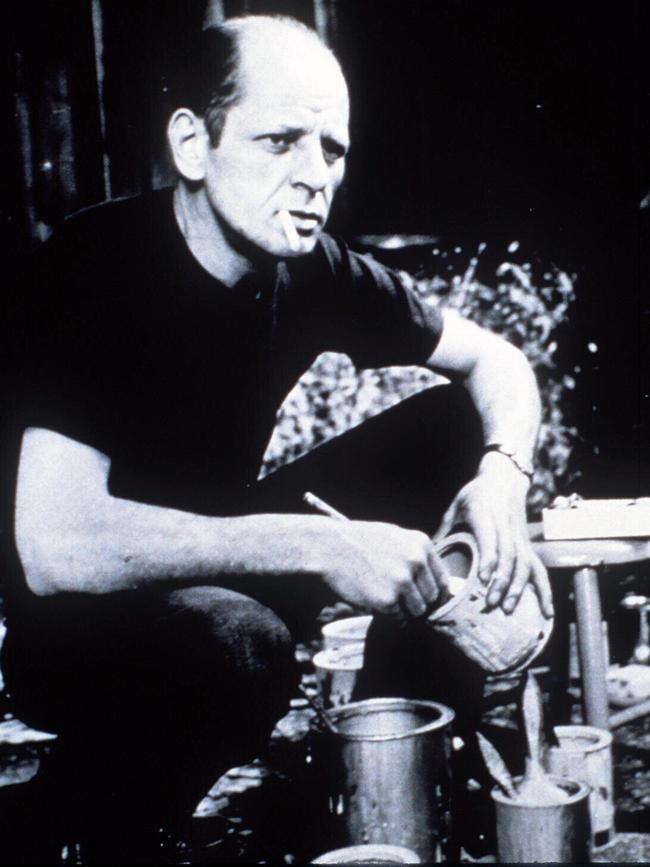

How the CIA weaponised the eccentric art of Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock had no idea that he was part of a CIA drive to burnish the West with soft power – unlike Putin’s overt efforts today to challenge Eurovision.

If you have ever stared in bewilderment at Jackson Pollock’s art, struggling to discern the meaning amid the chaos of his drip paintings, then you’re in good company. According to a new study by a team of psychiatric experts, the artist himself may not have realised what he was painting, having inserted “unconsciously encrypted images”, including a charging soldier, the angel of mercy and “a monkey with goggles and wine”.

To readers sceptical about the merits of abstract expressionism, all this may sound very dubious. But there’s no doubt Pollock’s paintings did carry one hidden meaning – a political significance entirely unknown to the artist himself, courtesy of the Central Intelligence Agency.

In an age when we are increasingly suspicious of anything we come across online, no matter how apparently innocuous, the story of the CIA’s weaponisation of the arts during the Cold War feels oddly prescient.

As historian Frances Stonor Saunders shows in her spirited book, Who Paid the Piper?, the CIA spent millions of dollars in the 1950s and ’60s to promote avant-garde American culture, from abstract expressionism and pop art to jazz and opera.

The aim, as she puts it, was to show the US was a “sophisticated, culturally rich democracy”, in contrast with the drab conformity of the communist bloc. And though artists such as Pollock never knew anything about it, the campaign undoubtedly made a difference.

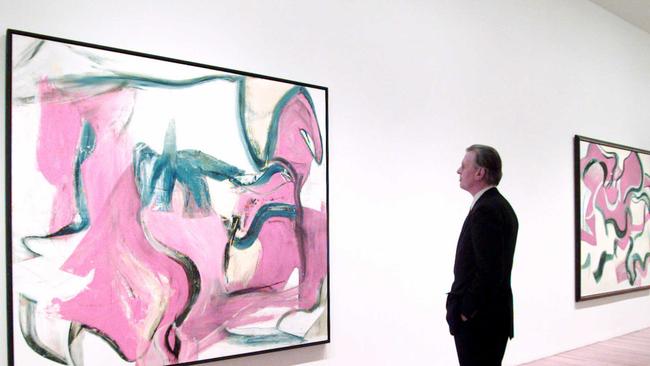

In 1956, London’s Tate galleries welcomed a touring show entitled Modern Art in the United States. The first major exhibition of American art shown in that country, it included works by painters such as Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning.

Many visitors found it utterly bizarre: the Evening Standard’s critic thought it “nightmarish”, while The Scotsman’s reviewer thought Pollock’s The She-Wolf looked like “Clapham Junction after a railway accident”. None of them, however, came away thinking American art was boring, and none doubted the greatest capitalist democracy on Earth was fizzing with energy and imagination.

That was just as the CIA’s spymasters had planned, since exhibitions of this kind were strongly encouraged by their lavishly funded front organisation, the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

It would be silly, of course, to pretend that abstract expressionism was nothing but a front for Cold War anti-communism. Had the Cold War never happened, Pollock would still have painted the same pictures and their impact would surely have been much the same.

Yet much to the subsequent embarrassment of left-leaning artists, there’s no denying the Cold War link. No major museum in the world did more to promote avant-garde art in the post-war decades than New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Its president, Republican politician Nelson Rockefeller, called it “free enterprise art”.

And when, in 1959, the Tate was struggling to find the cash for another touring exhibition, The New American Painting, who should pop up but a kindly American millionaire called Julius Fleischmann, who could think of no better investment than to share the joys of Pollock and de Kooning with the British public.

Yet according to Saunders, the cash didn’t come from Fleischmann’s private account. Instead, it came from a private charity called the Farfield Foundation, which drew its funds from the CIA.

Once again, not all of the exhibition’s visitors liked it. “It is the bottom: we can sink no lower,” declared an extraordinarily pungent review in The Daily Telegraph. “Hitler died too soon.”

But the controversy was part of the point. Free enterprise art was meant to be anarchic, in contrast with the stultifying predictability of socialist realism. And in New York and Europe, unlike Moscow and Leningrad, you were free to hate what you saw, and to say so.

When the first reports of the CIA’s involvement in the cultural Cold War emerged in the 1970s, many arts figures reacted with horror. But they were naive to imagine that art, literature and music can ever float free from the grubby realities of global politics.

Even the Eurovision Song Contest, after all, is political – at least according to Vladimir Putin, who this week signed a decree to set up a Russian alternative celebrating “traditional universal, spiritual and family values”. In this, as in so much else, the Cold War is still with us. Even the name of Putin’s proposed competition, the Intervision Song Contest, is a nod to a festival established in 1965 by Leonid Brezhnev and held in Czechoslovakia and then Poland.

Yet the Russian President should be careful what he wishes for, since musicians and their audiences are not always easy to manage. Even in the 1970s, Soviet acts were jeered by Polish spectators. Indeed, many listeners were much more interested in the Western acts invited to perform during the interval, such as Gloria Gaynor and, bizarrely, Boney M. Would Boney M be welcome to perform at Intervision today? Does a song such as Rasputin really promote traditional Russian family values?

The truth, of course, is that although it’s perfectly natural for politicians, like many kings and emperors before them, to use the arts, culture has a habit of slipping out of control. Even the Cold War campaign to promote modern American art was a much more chaotic, even comical enterprise than the standard accounts of cold-eyed CIA puppetmasters might suggest.

The very first Cold War exhibition, the State Department show Advancing American Art in 1946, was a case in point. Far from applauding their avant-garde compatriots, most conservative politicians were appalled by their experiments in artistic form.

Outspoken Michigan congressman George Dondero, for instance, told colleagues such “art trash” was undoubtedly part of a conspiracy directed from Moscow, which was the exact opposite of the truth.

Even president Harry Truman regarded this advertisement for American freedom with undisguised contempt. “If that is art,” he said, staring at Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s painting, Circus Girl Resting, “then I’m a Hottentot.” Perhaps his spymasters should have saved their money after all.

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout