Jackson Pollock’s $430m masterpiece Blue Poles’ royal conservation treatment

Once pilloried as massive con, Australia’s most divisive — and expensive — painting has gone under the microscope.

His brow creased with pain, Nick Mitzevich limps towards the painting that once generated global headlines, split the nation and provoked a verbal brawl in federal parliament. The National Gallery of Australia director is recovering from surgery on a torn knee ligament but, despite his physical discomfort, a knowing grin plays about his lips.

“This is Australia’s most talked about work of art,” he says, settling gingerly on to a bench in front of the abstract, wall-sized painting. “Regardless of whether they have visited it or not, everyone seems to have an opinion of Blue Poles.” Mitzevich is speaking, of course, about Jackson Pollock’s last monumental “drip” painting, which the Whitlam government bought in 1973 for $1.3m — then a record price for an American painting.

The purchase was freighted with controversy and drama; not only was the work abstract but its creator, Pollock, was the heavy-drinking, prototypical “action painter” who courted notoriety by pouring, throwing or squirting paint on to his large-scale canvases as he danced around them.

Mitzevich recalls that when he was appointed NGA director, “before I arrived in Canberra, people would say to me, ‘Oh, you’re gonna be looking after Blue Poles’ … It was amusing for me that even before I arrived two years ago, people were referring to the picture more [than his prestigious new job].”

On the day we meet, the nation’s flagship gallery is closed because of the coronavirus pandemic, and banks of high-powered lights and a 2m high microscope are trained on Pollock’s hotly debated work. Up close, and with the gallery emptied of visitors, it seems simultaneously a study in control and chaos, with its melancholy blue poles overlaid on vibrant tributaries of orange, yellow, silver and white. It’s dense in texture, operatic in scale and — even though it is 68 years old — electric with energy. It is also, says Mitzevich, “by far” the most commercially valuable painting in the NGA collection, and Review has been granted exclusive access to the crack gallery team that is at work on it. This curatorial and conservation team is conducting the most ambitious study and clean of Pollock’s painting since the gallery was opened by the Queen in 1982.

Because of its popularity and notoriety, Blue Poles is always on public display. But with the gallery recently closed for nine weeks by the pandemic, the NGA’s experts realised they could finally kickstart the project they had long wanted to carry out: to discover more about the fiendishly complex, multi-layered web of paint, staples and glass fragments that comprise the painting’s surface, and about how Pollock, who died in 1956, executed the work.

“It really is detective work,” says curator Lucina Ward, “and the aim is to ensure it looks as good for future generations as it does now … We have always been intrigued by the structure of Blue Poles because it’s got this notorious history, some of which was false.”

In 1973, as the economy barrelled towards recession, the Whitlam government raised eyebrows around the world when it bought Blue Poles for $1.3m — then the equivalent of $US2m, the highest price paid to that date for an American painting. Pollock, an abstract expressionist who battled serious depression and alcoholism for most of his life, had been regarded as a cowboy by some and a visionary by others. New York’s Museum of Modern Art had described Blue Poles as “the most important postwar American painting still in private hands”, while Time magazine had nicknamed Pollock “Jack the dripper”.

Armed with one of the biggest acquisition budgets of his era, the NGA’s founding director, James Mollison, was the prime mover behind the Blue Poles purchase. As he put together a collection for the yet-to-be built national gallery on the banks of Lake Burley Griffin, he famously declared: “We are only interested in acquiring masterpieces.” Underlining the boldness — or extravagance — of the deal, Blue Poles held the record as the most expensive work by a US painter for a decade.

In a candid gallery documentary, former NGA curator Christine Dixon says the $1.3m price tag “created so much controversy because Australian taxpayers thought it was a waste of money’’. In 1973, the Metropolitan Museum of Art had bought a Rembrandt for the same sum. At the time, says Dixon, many Australians saw abstract painting as “a sort of con. They thought we were being taken for a ride by these slick New York art dealers.”

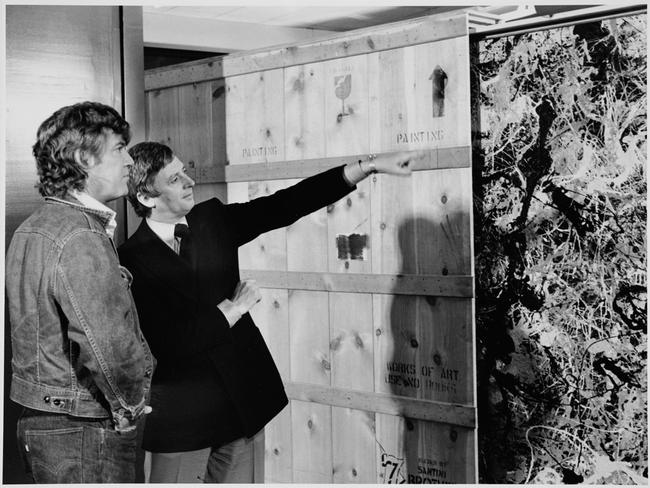

Even before the painting could be shipped to Australia — it was craned out of the previous owner’s Manhattan apartment window — the controversy deepened. In 1973, New York magazine published claims the work was the product of a drunken collaboration between a suicidal Pollock and his artist buddies Tony Smith and Barnett Newman. Although the claims were debunked, they were widely recycled. In Sydney, The Daily Mirror’s poster declared: “$1mill. Aust. Masterpiece. Drunks did it”. Questions were asked in the Senate about whether the federal government had squandered taxpayers’ money on the results of a drinking binge.

New York-based Australian art critic Robert Hughes was among those who recommended Australia buy the painting, arguing that it was “a feat of lyric invention” and “certainly the most important American picture, perhaps in all time”.

Mitzevich says Blue Poles is now regarded as “one of the most important paintings of the 20th century”. He reveals its insurance value has grown to more than $US300m ($437m). While a work’s insurance value can differ from its market price, Mitzevich speculates that the painting would “far exceed” that sum [$US300m] on the open market. “Since we bought the work, Jackson Pollock has been defined as one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century, and most art scholars believe this to be one of his most significant and resolved works,” he says. (Pollock’s painting Number 17A sold to a hedge fund manager for $US200m in 2015, and another work, Number 5, 1948, fetched $US140m in 2006, according to the World Economic Forum website.)

As the gallery boss speaks, most of the exhibition spaces in the shuttered brutalist building are deserted and silent, but for the echoing of staff members’ footsteps. When Review visits, Ward and conservator David Wise are five weeks into the conservation project, and they have already made important discoveries about Blue Poles, aided by their high-powered microscope, infra-red and ultraviolet digital photography and historical photographs. They say their research is reinforcing the view that, far from being the product of a paint-flinging frenzy, it is one of Pollock’s most “considered” paintings.

However, the man who was described as the “shock trooper of modern painting” did not make life easy for conservators. He believed his abstract works captured “the inner world” of the subconscious, and he spurned the conventional tools, methods and materials of his craft as he poured, flicked and squirted paint on to his canvases. He liked to use stick-like, dried-up brushes or syringes and, by accident or design, pieces of glass, metal staples and a thumb print have ended up on Blue Poles’s surface.

In a further challenge for conservators, Pollock used 1950s commercial paint — or house paint — to execute the work, a material not as well understood as traditional artists’ oil paints. Explains Ward: “It’s kind of extraordinary to think about that — Pollock is, very crudely speaking, using in effect, commercial paints, house paints.”

She glances at the monumental canvas before her: “If your house looked this good, and this gorgeously bright, after 70 years you’d be pretty happy, wouldn’t you? We’re dealing with an area that’s not much studied because oil paints and binders have existed since the 1400s and 1500s. We’ve got a long history of those to study. We don’t have a long history of aluminium and synthetic polymer paints.” (Pollock also used oil paint in the work. Blue Poles’s official gallery label lists its components as oil, enamel, aluminium paint and glass.)

Ward says the pigments used in traditional artists’ paints and house paints “can be the same, but the binders can be different”. Moreover, to facilitate his “large gestures”, Pollock made his paints “more liquid” and used dried-up brushes. “They’re better described as sticks,” says the curator. “He’s using syringes, too, to kind of flick the paint, and we just don’t have a history of painters doing those things to deal with.”

According to Wise, tinned commercial paints “age differently to artists’ paints (because) they’re made of different materials. It’s an area of real interest to modern conservation because all the paintings that were made of these are getting old and beginning to change. He was at the forefront of that movement … of using non-traditional paints.” (Other celebrated 20th-century painters, including Willem de Kooning and Sidney Nolan, also experimented with commercially produced paints.)

The conservator has obtained “an extraordinary amount of surface detail” about Blue Poles from the microscope, which is hooked up to a computer screen, allowing him to home in on areas as small as 1sq cm. Crucially, Wise has found no evidence of fading. He says the pigments in the house paint “are quite stable. When we look at early images of Blue Poles, we can see that … there has been no change in intensity of colour.” He has detected “a slight darkening perhaps overall” in the work’s colour tones that is “potentially to do with the ageing of the resin binder the paints are made of”.

Despite the controversy about Blue Poles’s genesis, the NGA team believes Pollock may have worked on the painting for six to eight months. (The artist’s wife, Lee Krasner, said Pollock was often frustrated by it, lamenting that “this won’t come through”.)

Wise points to a section of the Belgian linen canvas where yellow paint flows through orange to give a marbling effect. This means these colours were applied at roughly the same time, mingling before they dried. But in other areas of the canvas, orange paint sits on black or silver paint discretely, indicating the orange went on after the other colours dried. “That’s evidence of time; a gap of activity. It’s kind of a myth about abstract expressionism that it’s done in this frenzy of activity, in reality it’s not like that. It’s actually a considered process,” he says.

What would Blue Poles look like without its enigmatic poles, which have been interpreted as Native American totems, ancient stick figures or the masts of storm-tossed ships? To investigate what lies beneath, the conservation team use infra-red technology, which renders the poles invisible. Suddenly I am looking at the work without its defining feature — and surprisingly, a pole-less Blue Poles looks more organised and schematic than the completed work. “It looks a lot more like Pollock’s other late works,” says Ward. (Yet some critics have argued it is the poles that impose a “rhythmical” order on the painting.)

In 1998, Blue Poles was spruced up before it was sent to New York for a Pollock retrospective at MoMA. The current investigation is laying the groundwork for a clean that will go further than previous treatments. Wise is looking at whether “other things have been added to the surface — varnishes and such — which we may be able to address. That’s where this project is different from previous projects. It’s a bit more of a dramatic intervention.”

He believes a coating has been applied to some areas of the painting but is unsure what it is. He is still examining whether it’s a foreign material added to the canvas after it was completed or a case of elements in that 1950s house paint separating. I ask whether it’s intimidating to be working on a painting worth hundreds of millions of dollars. “No,” he replies emphatically, pointing out that his job is about protecting the work, so he doesn’t take any unnecessary risks.

The conservation project is steering clear of the controversy about the painting’s origins because the gallery believes the claims Blue Poles was created by Pollock and two “loaded” artist mates were refuted long ago. Before the painting arrived in Australia, it was inspected at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. According to the NGA website, “The examination revealed that any marks made on the canvas by Smith or Newman played no part in the painting that became Pollock’s Blue Poles.”

Ward concurs that “while the origins of the canvas … had something to do with the visit by Smith and Newman to Pollock’s studio … Neither of them accepted their involvement in the work of art that was Blue Poles. They accepted that they marked the canvas. That’s the level of their involvement.”

She says Smith and Newman were attempting to coax Pollock out of a depressive “low” and back into working with colour. “Pollock drank a lot,” she says. “He drank often out of frustration. He drank when he wasn’t working. He sought treatment for alcoholism and depression from the late 1930s. In the run-up to this work of art … basically he was in a low.” Smith told New York magazine Pollock was suicidal and holding a large carving knife when he visited him in 1952.

Born in 1912 to farmers of modest means, Pollock continued to be plagued by depression and alcoholism, even after his artistic reputation solidified. In 1949, American art critic Clement Greenberg described him as America’s greatest painter, and Life magazine responded in a half-jeering way: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Despite the sceptical tone, Life’s coverage of Pollock helped turned him into a bona fide art star: the epitome of denim-sporting, boundary-bending, bourbon-swilling cool.

Pollock certainly lived on the edge and in 1956, aged 44, he crashed a car while drunk, killing himself and a female passenger. (Pollock’s mistress survived the accident.) Biographer Deborah Solomon said that when he died, Pollock’s public image was of a “paint-flinging cowboy who came out of nowhere to shock the civilised world with the rawness of his vision”.

In subsequent decades, this view changed dramatically and the value of his paintings soared. The catalogue to MoMA’s 1998 retrospective stated: “Jackson Pollock is widely considered the most challenging and influential American artist of the 20th century.” Yet during his lifetime he never sold a painting for more than $US10,000.

Back in Canberra, the NGA has reopened and the Blue Poles conservation work is continuing in situ, in the exhibition room that has long been home to the painting initially known as much for its sale price as for its aesthetic qualities. “We thought the audience would find it fascinating to witness and be a part of the work as it’s investigated and cleaned,” Mitzevich says.

The NGA boss says that these days, many of the gallery’s one million or so annual visitors look at the work “not with scepticism but with awe. Pollock did what extraordinary innovators do — they change our understanding of things. He charts new territory and asks us to look differently on the world. There’s a general acceptance that this is one of the most treasured cultural items we have in this country, and it’s also verified by the art market.”

Despite the controversies that attended its acquisition, he says owning Blue Poles “defines the gallery as an important cultural player” and a leading collecting institution: “The fact that we own Blue Poles means that galleries around the world have a greater confidence in us and means we can secure loans … It does bring lots of benefits to Australia.”

Once the conservation project is finished, the gallery is planning more Blue Poles events in 2022 to mark the work’s 70th birthday and the gallery’s 40th anniversary. This month, the NGA has launched a new microsite, titled Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles: Action/Reaction that includes footage of the conservation project, archival footage and historical photographs that tell the story of this once-polarising painting. Previously derided as an overpriced collection of “dribs and drabs”, Pollock’s painting is now an emblem of Australia’s modernity and internationalism. “You can’t escape this work,” says Mitzevich. “This work is part of who we are.”

Watch a video of Blue Poles at the NGA’s microsite: www.nga.gov.au/bluepoles

READ MORE: No audience? No worries. Tattooed human artwork walks out of Mona | Coronavirus: Silver lining in National Gallery of Australia’s lockdown blues

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout