Fate of Nazi monster Alois Brunner lies in Assad’s ruins

Alois Brunner evaded the Allies in 1945 and was welcomed by Syria but the mystery of how and when he died persists.

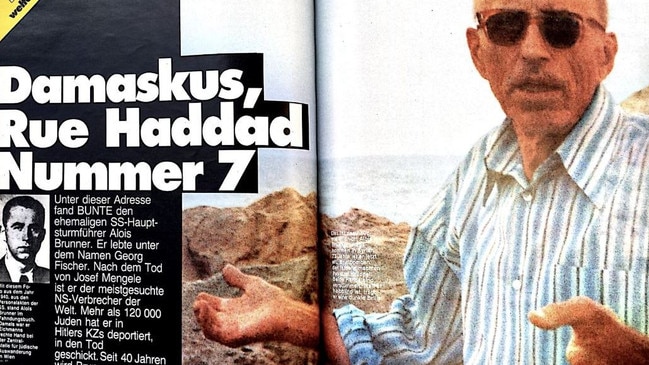

On September 13, 1961, a tall, balding man with “spiteful eyes” (according to a CIA report), collected a large package from a Damascus post office addressed to “Abu Hussein”.

He took the parcel home to his luxury apartment on the Rue Georges Haddad in the diplomatic quarter of the Syrian capital and opened it, whereupon the packet exploded, removing his eye and parts of his arm.

The bomb was a gift from Yitzhak Shamir, later prime minister of Israel but then head of Mifratz, the special operations unit of Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service.

Hussein’s real name was SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Alois Brunner, one of the world’s most wanted Nazis, a mass-murdering monster nicknamed “the bloodhound” who was personally responsible for deporting 128,500 people to death camps.

The bomb did not kill Brunner, who would live on for many more years as a favoured guest of the Assad family and special adviser to the Syrian regime on torture techniques. He was never brought to justice. Then, about 20 years ago, he vanished.

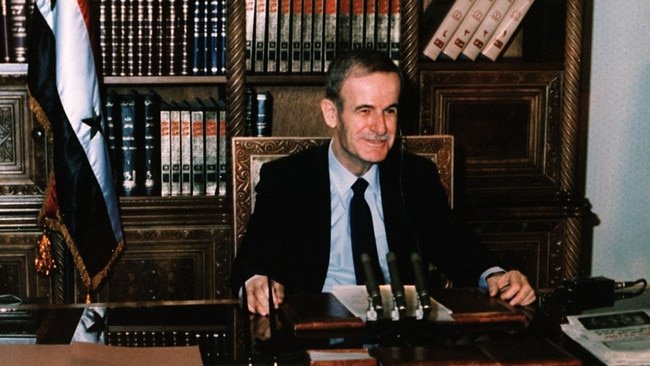

Of the multiple crimes committed by the Assads, one of the more perverse was their protection of Brunner, defying every effort to extradite, try or kill him.

Victorious Islamist rebels in Syria are now combing through the bureaucratic files of the ousted government, vowing to bring the regime’s killers and torturers to justice. In the process they may finally solve one of the great historical mysteries of the 20th century: the fate of Alois Brunner.

Austrian by birth and violently antisemitic by conviction, Brunner was an early member of the Nazi party. By 1938 he was a senior SS officer responsible for “cleansing” Austria of its Jewish population.

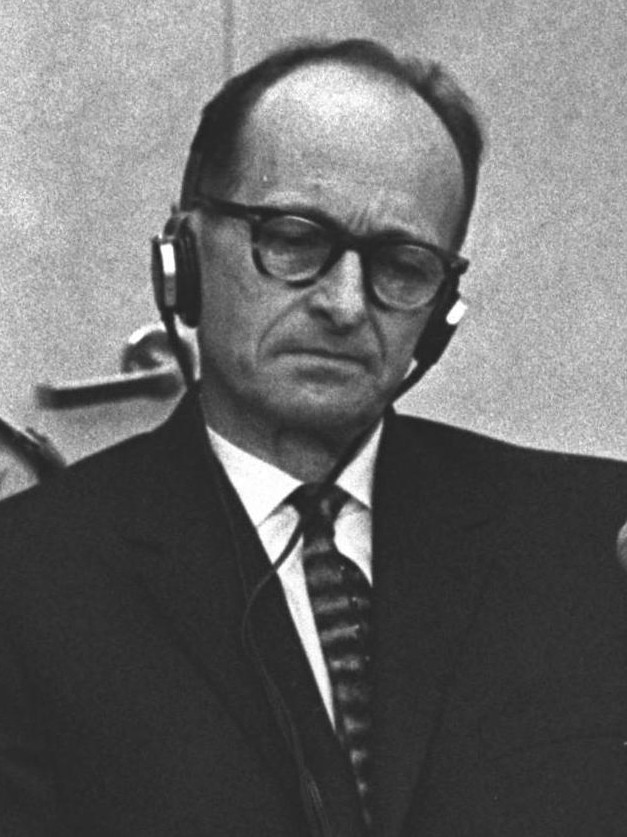

Adolf Eichmann, the logistical organiser of the Holocaust, referred to Brunner as his “right-hand man”. Brunner deported thousands of Jews to death camps from Austria, Greece and Slovakia. He subsequently oversaw accelerated deportations from Paris to Auschwitz. He relished his appalling work.

After the war he escaped capture after being confused with another SS officer, Anton Brunner, who was tried and hanged. The real Brunner worked undetected as a US army driver before moving on to Rome, under the pseudonym Dr Georg Fischer, and then Egypt, where he became an arms dealer supplying weapons to Algerian rebels fighting for independence from France.

By 1954 (the year he was sentenced to death in absentia in France for crimes against humanity) Brunner had settled in Syria, welcomed by President Hafez al-Assad for his brutal expertise. Living in comfort in Damascus on a substantial government salary, he advised the regime on structuring its spy services, instructed Kurdish separatists on staging attacks in Turkey and trained Syrian officers in the grim techniques of interrogation: some of those torture methods were still being used in Syria’s prisons and detention centres when the regime was toppled last week.

After Eichmann was captured by Mossad in 1960, Brunner suggested that the Syrians mount a seaborne commando operation to liberate his former boss from an Israeli prison (Eichmann was hanged in 1962).

The Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal wrote: “Among Third Reich criminals still alive, Alois Brunner is undoubtedly the worst. In my eyes, he was the worst ever. While Adolf Eichmann drew up the general staff plan for the extermination of the Jews, Alois Brunner implemented it.”

The Syrian government flatly ignored repeated extradition requests from France, Czechoslovakia, Austria and Germany. A second Mossad parcel bomb blew off four fingers of his left hand in 1980.

“Brunner is known to be protected in Syria by guards, presumably from the Syrian intelligence services,” William L Eagleton, the US ambassador to Syria, wrote to the American secretary of state George Schultz in 1984. Brunner enjoyed his notoriety, chatting with tourists outside his apartment and giving interviews to the press.

In a 1987 telephone interview with the Chicago Sun-Times he remained vigorously unrepentant for his central role in the Holocaust.

“All of them deserved to die because they were the devil’s agents and human garbage. I have no regrets, and I would do it again.”

According to one member of Assad’s inner circle, Brunner was a “card that the regime kept in its hand”.

In the late 1980s, Syria appeared ready to extradite him to communist East Germany in exchange for a trade deal, a plan scuppered by the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Brunner remained a symbol of Assad’s power: an assertion of Syria’s independence, a repudiation of global norms and values and a deliberate affront to neighbouring Israel. “Damascus has a perverse sense of pride which would prohibit turning the former Nazi over to any western authority, since this would be perceived locally as giving in to Israeli pressures,” the US embassy recorded.

The knowledge that Syria’s security forces had been trained by a Nazi murderer reinforced the regime’s cult of fear. Almost 60,000 people were tortured and killed in Assad’s prisons, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

But when Bashar al-Assad succeeded his father, the new president sought a more reformist image, and the elderly Nazi on Rue Georges Haddad became an embarrassment. From 1989 Brunner lived under virtual house arrest, subsisting on army rations in a windowless basement beneath Syria’s security headquarters.

He was last seen alive in 2001, at the Meridien Hotel in Damascus. According to one report he died in December of that year, at the age of 89, and was secretly buried with Muslim rites in al-Affif cemetery. The Simon Wiesenthal Centre declared he had died in 2010.

The “Brunner Archive” was securely held in the presidential palace. While joyful looters are scooping up mementos of the fallen dictators, others are systematically gathering files for a settling of scores.

Nazi hunters have long since abandoned the search for the fugitive Brunner. But the truth about the Assads and the mass murderer they embraced, employed and sheltered for half a century may soon be found amid the wreckage of the Syrian regime.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout