Adolf Eichmann biography reveals another Nazi piece of work

A NEW biography of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi responsible for the mass murder of Jews, snuffs out any possibility of innocence or denial.

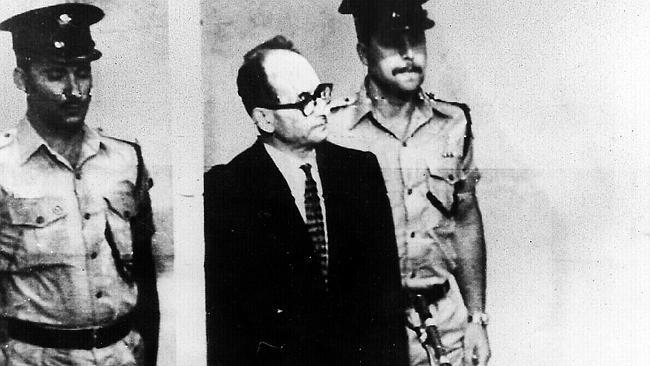

ADOLF Eichmann, SS Obersturmbannfuhrer, was one of the Nazis primarily responsible for the mass deportation and murder of European Jews between 1939 and 1945.

After the Allied victory he went into hiding, first in Austria, where he farmed eggs, and later in Argentina, where he lived with his wife and children as part of Juan Peron’s community of Nazi sympathisers.

Eichmann was absent from the Nuremberg war crimes trials and came to be known as ‘‘the Nuremberg ghost’’. In 1960, he was kidnapped by a Mossad team and taken to Israel, where he was put on trial in 1961. Most observers of the trial noted that he showed no remorse and that he spoke willingly about himself. He was hanged in 1962. Today, Eichmann’s trial is considered a cathartic moment in the establishment of an Israeli identity.

His case is famous, in part, because of Hannah Arendt, who reported on the trial for The New Yorker, and in whose subsequent book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, a collection of reportage, the idea of ‘‘the banality of evil’’ originated. Arendt argued that Eichmann was neither maniacal nor particularly anti-Semitic, that he was ‘‘not a monster’’. Rather he was normal to the point of being mundane, a view supported by Eichmann’s presentation of himself at the trial.

Now German academic Bettina Stangneth has written Eichmann Before Jerusalem, which details his life before the trial — and aims to achieve what Claude Lanzmann achieved in the context of Nazi crimes in his film Shoah: snuff out any possibility of innocence or denial.

Working in and around Arendt, Stangneth presents Eichmann as a deeply ideological, fanatical careerist who saw himself as important and creative.

Her image of Eichmann is of much more than a mere functionary, and far from that of a normal man. In dialogue with Arendt, Strangneth creates a psychological portrait of Eichmann as deliberate, calculating and intelligent. He was proud of his ‘‘innovations’’ and thought a lot about his life’s work. The ways in which he spoke about himself while in power are at odds with how he spoke about himself at his trial.

Stangneth argues that the faceless functionary identity we associate with Eichmann is due to his wily ability to manipulate and deceive his listeners. She never goes as far as to suggest that Arendt, along with the rest of the world, was taken in by Eichmann — that remains unsaid, but open to interpretation. Stangneth carefully avoids mentioning Arendt’s name too often and when she does it’s with reverence. She makes use of a lot of evidence that was unavailable to Arendt.

This book is diligently researched and deals with the minutiae of Eichmann’s career and life in hiding. Stangneth presents sources that have never been examined before and, for the first time, closely analyses Eichmann’s own writing (much of which was about himself).

Crucial in her evidence is a series of interviews conducted by Dutch Nazi journalist Willem Sassen. Contrary to the autobiography he wrote in prison in Jerusalem, Eichmann not only did not deny that the murder of the Jews had happened, he asserted his active responsibility. Stangneth, who is clearly interested in power and in the psychological bullying of the Jewish community by the Third Reich in the lead-up to the Final Solution, convincingly showcases Eichmann’s subtle hypocrisies.

In doing so, she depicts the hand-over-the-heart ceremoniousness with which the Nazis viewed their work, perhaps best expressed by Heinrich Himmler (to whom Eichmann reported), in 1943: ‘‘Most of you know what it means to see 100 corpses lying side by side, or 500, or even 1000 lying there. To have persevered, disregarding exceptional cases of human weakness, to have remained decent: this has made us hard. This is a never-to-be-written page of glory in our history.’’

The ways in which Stangneth’s research is expressed sometimes lets down the quality of her work. Unlike most professional historians (she is a philosopher by training), she doesn’t shy away from emotion. In a chapter called The Devil Himself, Eichmann is referred to as ‘‘Satan in human form’’. She makes pronouncements that seem unsophisticated or even glib, such as: ‘‘Taking a good look in the mirror clearly didn’t cause him the same level of concern’’, and ‘‘those men around Himmler had a slightly idiosyncratic idea of honour’’.

Lies told at Nuremberg are described as ‘‘brazen’’, a cliche that makes the deception seem cheeky rather than immoral. ‘‘Anyone comparing himself to the King of the Jews has some real issues to work through,’’ Stangneth asserts. That Eichmann ‘‘had some real issues to work through’’ is something that may be taken for granted by today’s readers. Some of this language could, of course, be part of the translation from the German by Ruth Martin.

This book is a valuable resource, one that belongs in the canon. It’s an excellent complement to Arendt’s work, which has hitherto been the default book on Eichmann. The question that all readers of Holocaust literature ask themselves many times — how it could have happened, and how so many co-operated for so long — is appreciated.

Such things don’t ‘‘just happen’’, they are strenuously propelled by people. Stangneth does not refute Arendt, but the image she constructs leaves very little room for banality, and none for denial. For those mystified by Arendt’s assertion that ‘‘he never realised what he was doing’’, Stangneth has some explanations.

Anna Heyward is a New York-based Australian journalist.

Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer

By Bettina Stangneth

Translated by Ruth Martin

Scribe, 608pp, $45