A year is not a long time in politics. American history is full of examples of presidential fortunes that seemed doomed after a turbulent year, only to reverse course and produce triumph the next. The first 12 months of a presidency can prove especially volatile — and ultimately meaningless. Novelty wears off; excitement fades. And yet a year or two later, new opportunities arise. Popular memories are much shorter than an electoral cycle.

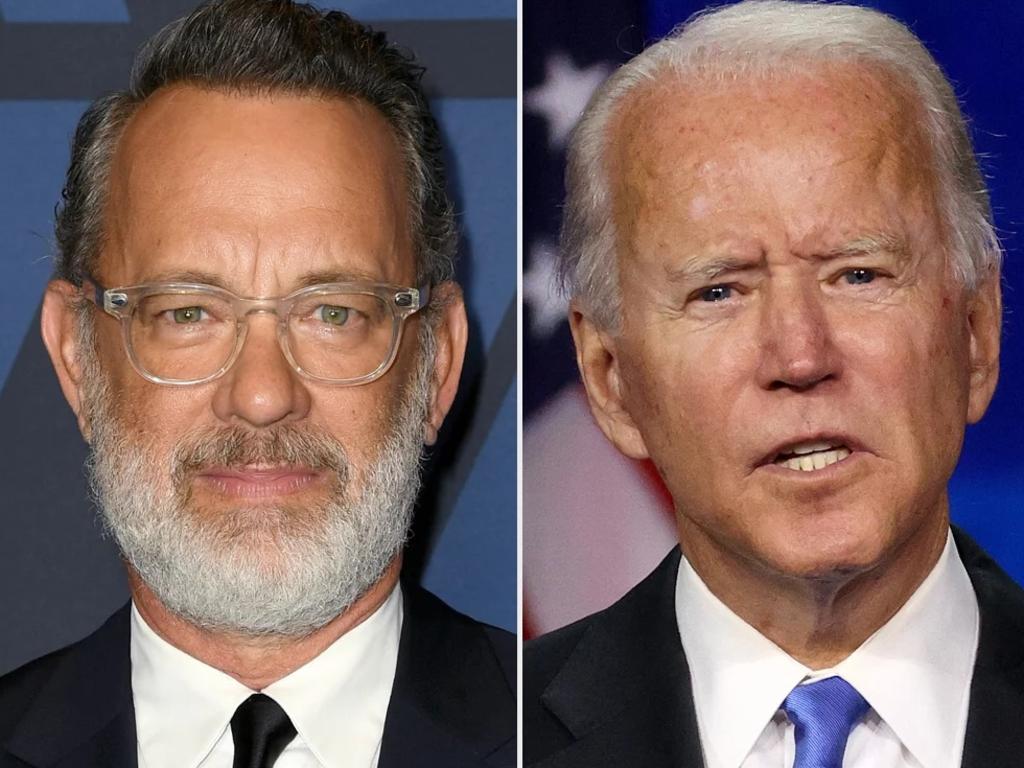

Still, there are bad years, there are very bad years and then there is Joe Biden’s inaugural year as president.

For his first anniversary in the White House this week, Biden is the most unpopular president at this stage of his term since polling began, with the single exception of his predecessor. But Biden’s predicament is more parlous than that of Donald Trump’s, who, throughout a wild four years of turmoil and an almost endless media barrage of loathing, never enjoyed an approval rating above 50 per cent.

Approval rating plummets

Biden, by contrast, stood at 56 per cent when he took office, a respectable number in a divided nation. According to the latest poll from Gallup, which has been collecting the data for almost a century, his approval rating stands at 40 per cent. Other pollsters have the number even lower: one put him at 33 per cent.

Presidents have clawed their way back from similar depths. Time, we have noted, is on their side. To understand whether Biden is Jimmy Carter or Bill Clinton, it’s necessary to answer two questions: what went wrong and how does he propose to fix it? Getting the first right is an essential precondition of producing the correct response to the second. Unfortunately for the dwindling band of Biden fans, the signs are not encouraging on either front.

Inconsistent policy, finger-wagging authoritarian

Everyone is allowed to indulge a little in self-denial. The fault is indeed almost always in ourselves and not our stars. Biden certainly seems to have convinced himself that events beyond his control have delivered him to his predicament. At a long press conference to mark his first anniversary this week, he explained what had gone wrong. “I have probably overperformed what anybody thought would happen,” he said, without irony, but he insisted he had been the victim of events.

The Covid crisis had persisted in severity and reach longer than he’d expected. Supply-chain disruptions caused by the pandemic had resulted in surging inflation. And above all, malevolent Republicans in Congress had prevented him from getting crucial legislation passed.

None of these excuses bears much scrutiny. Yes, Covid hovers still like a dark cloud, but Biden’s policies have contributed to the popular unease by being both weirdly inconsistent and finger-waggingly authoritarian. Inflation is a global problem — yet the first thing he did on taking office was to throw trillions of dollars at an economy already generating inflationary pressures.

And it’s not Republicans who have blocked his legislative program. It’s his own party. Just this week, his latest signature initiative — to pass a law that would take control over elections away from the states and place it in the hands of the federal government — failed because two Democratic senators declined to vote for the procedural rule changes that would allow it to pass.

Blaming Republicans, tilting at windmills

Blaming cruel fate and crueller Republicans in any case misses the larger reason for the president’s lowly standing. Biden and his Democratic colleagues have spent the last year tilting at the windmills that occupy such a large space in the modern progressive mind that they have taken their eyes off the daily obligations of governing a fragile and fractured nation.

His ideologically zealous allies seized on the pandemic from day one not as a crisis to be remedied with pragmatism and prudence but as an opportunity to build a new American social compact.

They came up with multi-trillion dollar spending plans to transform the economy; directed the nation towards redressing its historical sins through re-education in schools and workplaces; and insisted they were in an existential struggle to save democracy from armies of white supremacists and disgruntled Trumpists. Meanwhile, Americans just wanted someone focused on returning their disrupted lives to normal, stopping their shopping bill from rising every week and trying to heal — as Biden had promised — the nation’s wounds.

It’s this misalignment between the ideological aspirations of the people in power and the quotidian concerns of the governed that most explains Biden’s calamitous fall in esteem.

No sign of lessons learnt

But there’s no sign that the lesson has been learnt. Though he acknowledged the need for a fresh start this week, the president’s proposed new course of action was revealing: he’s going to spend more time listening to “experts and historians” to get a sense of what the country needs. Heaven save us from presidential historians.

More revealing was the indication he gave of his real strategy for seizing back the initiative. He doubled down on his accusation that efforts in a number of Republican-controlled states to tighten electoral laws, after the emergency provisions allowed for the pandemic election of 2020, represented a gross suppression of voting rights.

Asked whether that meant he thought the results of the midterm elections this year would be illegitimate, he said it would depend on whether the Democratic voting bills succeeded: “I’m not saying it’s going to be legit. The increase in the prospect of being illegitimate is in direct proportion to us not being able to get these reforms passed.”

Those efforts went down to defeat this week. So now the president’s primary message for this year is to pre-emptively reject the results of elections that go against him.

Where have we heard this before? That’s right, the Biden Democrats are readying themselves to echo Trump’s denunciation of a “stolen election”. It’s one way to deal with your unpopularity. But it doesn’t do much for the democracy you pledged to defend.

The Times