Facebook’s nuclear option marks a shift in Silicon Valley fight with media

In the decade-long fight between Silicon Valley and the media, last week will go down as a turning point.

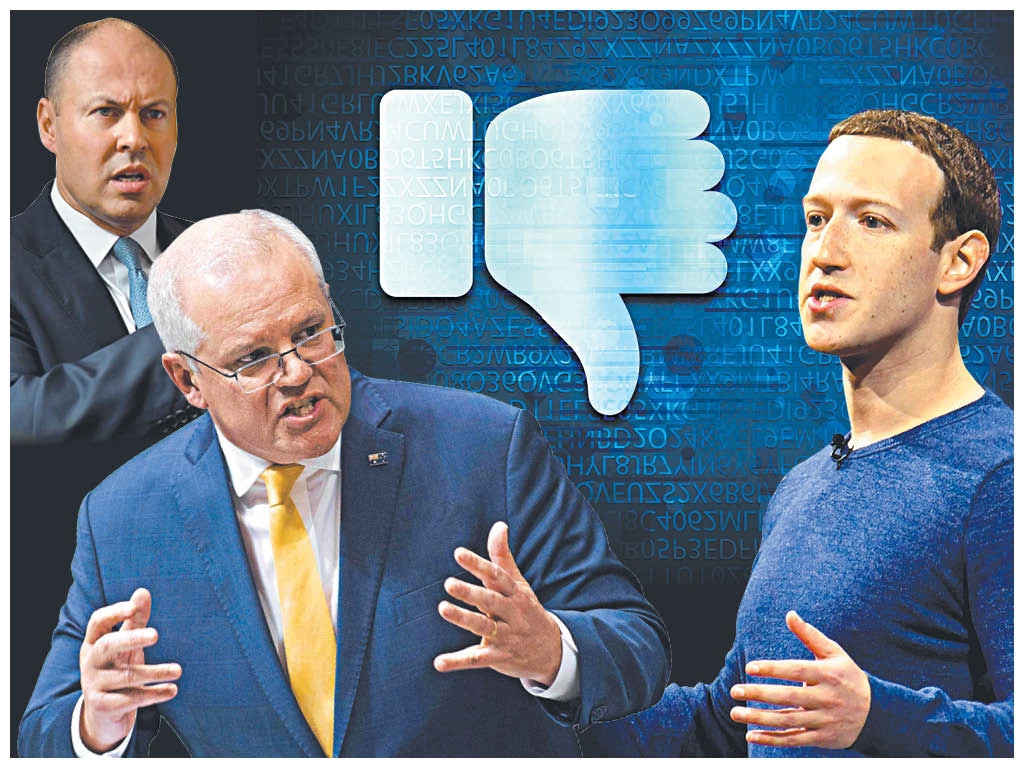

In the decade-long fight between Silicon Valley and the media, last week will go down as a turning point. Facebook hit the nuclear button in Australia and banned its 17 million users there from reading and sharing news on the platform, in anticipation of a law that will require social media giants to pay publishers for such content. Google took a different route — agreeing, finally, to share some of its revenue.

The search engine, which had threatened to shut down in Australia rather than comply with the “unworkable” law, struck a three-year agreement with News Corp, parent company of The Times and The Sunday Times and one of the country’s most powerful media organisations. The deal includes “significant” payments from Google, collaboration on a subscription platform, and development of audio journalism and video content for YouTube, part of the Google family.

Regulators in Britain, the EU, America and elsewhere watched the drama unfold. Most of the vitriol was, predictably, directed at Facebook. David Cicilline, the US congressman who led last year’s Big Tech inquiry, said: “Facebook is not compatible with democracy. Threatening to bring an entire country to its knees to agree to Facebook’s terms is the ultimate admission of monopoly power.”

Julian Knight, chairman of the Commons digital, culture, media and sport select committee, said the company’s “bully-boy tactics” would backfire on it.

The outcry comes amid a concerted, global effort to redress an imbalance that has seen the trillion-dollar tech platforms grab advertising revenue that once flowed to newspapers, resulting in mass lay-offs, closures and the rise of misinformation. Newsroom staff halved in America between 2008 and 2019 — and that was before the pandemic pushed more publications over the edge. Many of the survivors are dependent on the platforms to drive traffic to their websites.

The question is what happens now that Australia’s attempt to strong-arm Silicon Valley into paying for content has, at least partially, worked? (Google also inked a deal last week with media companies Seven West and Nine, and is in ongoing discussions with the ABC.)

Ken Doctor, an analyst and founder of Lookout Local, a media start-up in California, reckons this is the beginning of a new era for the industry. For an idea of how it may play out, look to television, he said.

There used to be just a few TV channels, and their airtime was largely filled with local programming. The rise of cable and satellite services changed that. As they rolled out “bundles” for customers, with dozens and, later, hundreds of channels, they included the local stations but they did not pay them. The thought of doing so was a non-starter. Cable tycoon John Malone said in 1993 that it would lead to “a blood-let on both sides”. It was not until the mid-2000s that the companies, under immense regulatory pressure, started paying “re-transmission fees” to local broadcasters.

At first, the fees were small — little more than gestures. Today, they are vital income. EW Scripps, which has 60 stations across America, last year brought in $US382m ($485m) of re-transmission fees from giants such as Comcast and AT&T. That equates to nearly 40 per cent of sales for its core local media business. In 2010, the fees accounted for a single-digit share of revenue. Scripps is not unique. Re-transmission fees across the industry totalled just $US28m in 2005. Last year they were set to top $US12bn, according to S&P Global.

Doctor expects Google, and possibly Facebook, to follow a similar path with the news industry. “This platform money is a new form of re-transmission fees for the publishing companies,” he said. “The question is: how much of this platform money will go out, and who gets it?”

Australia’s experience is instructive. The proposed law — the news media bargaining code — will require tech platforms to pay publishers whose articles appear on their pages. If they can’t agree on a sum, a third-party arbitrator will decide.

Google found the law so onerous that it threatened to shut down its search function altogether. Facebook, in explaining why it banned news links, said that it provided 5.1 billion “free referrals” to Australian publishers last year, worth more than $400m. News from media companies, it added, accounted for only 4 per cent of content in its News Feed. The message: the news business needs Facebook, not vice-versa.

Which is why the two companies reacted differently.

News is a core part of Google’s product. Organic search results shorn of news articles would plainly be less relevant, so it swallowed its objections and started making deals. For Facebook, journalism is, it argued, incidental to its core social network and the new law is simply intolerable, as it would in effect require Facebook to pay newspapers for the links they post to their own stories.

Even Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the web, sided with Mark Zuckerberg. In a submission to the Australian Senate last month, he wrote: “The ability to link freely — meaning without limitations (on) the content of the linked site and without monetary fees — is fundamental to how the web operates. If this precedent were followed elsewhere, it could make the web unworkable around the world.”

When asked after the News Corp deal whether Google would be subject to the rules once the law passes, the answer from Australia’s Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was telling: “If commercial deals are in place, it changes the equation.” The law, then, appears to be less about creating an industry framework and more about forcing Big Tech and media companies to sit down and make deals. Having agreed to pay one of media’s big guns, Google may now get a pass on complying with the rules for the small publishers that desperately need the cash.

Which goes back to Doctor’s question: who gets the money? Google struck a deal with French publishers last month to pay for some content. Facebook has handed $US100m to 50 local newspapers in America to help them through the pandemic.

Silicon Valley is opening its wallet; platform money may become a vital income stream that props up the media industry. But, like the cable companies in the 2000s, Big Tech will have to be dragged, kicking and screaming. Doctor said: “They will accede as much as they have to, giving as little as they can to as few as possible.”

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout