The great face-off against Facebook: the world is watching us

Make no mistake, we are in a war between Australian sovereignty and global digital monopoly and the world is watching.

The Morrison government’s “world first” mandatory code to force Google and Facebook to pay for news content has made Australia the initial frontline of this global battle with the two giants following different tactics — Google has negotiated and finalised deals while Facebook has declared a digital war.

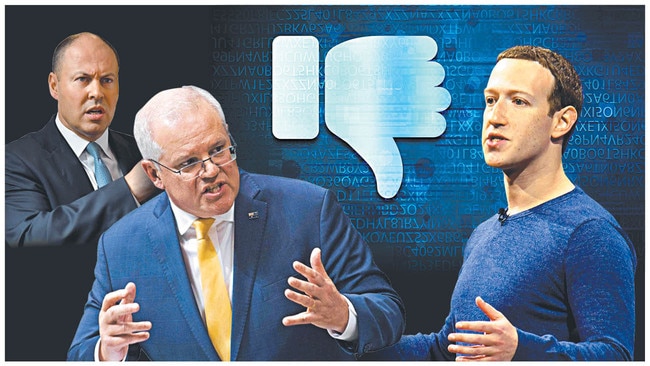

Going to the essence of this struggle, Josh Frydenberg told Inquirer: “It’s hard to think of another economic policy decision where Australia has led the way globally than what we’ve done with digital platforms.” But this week the Treasurer has walked a risky fine line — he has censured Facebook for its retaliation against Australia but tried to persuade its founder and boss Mark Zuckerberg to back off and cut an agreement with our media companies.

After speaking with Zuckerberg last weekend Frydenberg was blindsided on Thursday when Facebook blocked news content and news sites — along with many government, community and safety sites — trying to intimidate the Morrison government into retreating on key aspects of its media bargaining code.

“Deals were relatively close,” the Treasurer said. But Facebook had a different view. Its actions triggered a moment of truth and opened a global spectacle. “Facebook responded to a code designed to curb its market power with an abuse of its market power,” Frydenberg said on Thursday. Its action was brutal yet ironic.

Facebook verified the need for the bargaining code by showing its willingness to sabotage news and public interest content to further its financial interest; it showed by this action it was not just a publisher asserting its rights over content but an irresponsible publisher; it was ready to use the 11 million Australians using Facebook as collateral damage in its intimidation campaign; and it exposed its contempt for the Australian government and, beyond that, for Australian sovereignty.

The message could not be more obvious: big tech is not our friend. It sees our law and democracy as impediments before its own interests. It seeks to publicly break the will of Scott Morrison, Frydenberg, the Australian government and parliament in their quest to better regulate big tech. Indeed, Facebook seems unconcerned about the public backlash it has provoked, apparently convinced about the irresistibility of its model.

But the pivotal lesson from this week is in danger of being lost. It is the test of success — and that test is getting a viable media bargaining code legislated. This is what matters for Australia, for public policy and for journalism. The test is not getting Facebook signed up. If that is the test the government has no bargaining position at all.

With Google doing commercial deals the code already has its launch power even before it becomes law. The real issue has changed. It goes to the question confronting Facebook: will Facebook sign up to Australia’s code or will it stay out? But Facebook cannot make or break the code. The Labor Party in some confused public statements missed the point. Facebook’s menacing actions against Australia reveal the authoritarian strand in big tech. It is proof of the proposition argued by Financial Times journalist Rana Foroohar in her 2019 book Don’t be Evil — that big tech companies “are bifurcating our economy, corrupting our political process and fogging our minds”.

As Australia engages in combating another hi-tech threat, clandestine interference from China, a Leninist state, it faces a different type of interference in the form of brazen intimidation by Facebook. The upshot is that by a mixture of decisions and events, the Morrison government has brought Australia to the epicentre of two global struggles — reining in the American big tech giants and being the spotlight in Beijing’s retaliatory assertion. In both cases Australia has become a test case for global outcomes.

In the Zuckerberg-Frydenberg talks one theme is dominant — the real issue is not Australia as such. It is the precedent-setting nature of Australia’s law. Zuckerberg is not worried about what cash the Australian code might force him to deliver to the media companies but is worried about the financial impact of this precedent going global.

The question, still unanswered after the Frydenberg-Zuckerberg talk Friday morning, is whether Facebook is bargaining to maximise its leverage or is ready to punish Australia permanently by keeping news content off its platform. Their talks will continue over the weekend. But there is one certainty — the Australian backlash is strong and extends to both sides of federal politics.

Three weeks ago Google Australia chief Melanie Silva told a Senate committee the company would deny its search engine to this country if the law was passed. “It’s not a threat,” she said. “It’s a reality.” The Prime Minister and Frydenberg took this threat seriously and prepared a plan B with Microsoft. While Google did a rethink, Facebook has pressed the ultimate button. When it happened on Thursday morning it was a shock but we should not have been surprised — the warning was on the table.

The different tactics of Google and Facebook shaped the week. Frydenberg and Google chief Sundar Pichai formed a basis for understanding.

Last weekend the Treasurer had eight to 10 conversations with Pichai, going back and forth with Morrison and Australian Competition & Consumer Commission chief Rod Sims sorting out technical changes to the code to help Google across the line.

The code has three elements — it is mandatory; it addresses bargaining power imbalances to ensure digital platforms pay for the content they use from news media companies; and it has arbitration as a final step. The government will legislate the code. “We will not be intimidated by this act of bullying,” Morrison said on Thursday. The bill has passed the house and gone to the Senate.

The aim of Frydenberg and Communications Minister Paul Fletcher has been to use the code as a catalyst to drive upfront commercial deals. The agreements Google has cut with Seven West Media, Nine Entertainment and News Corp (publisher of The Australian) vindicated the strategy. “This code has succeeded where others have failed,” Frydenberg declared on Wednesday knowing the big News Corp deal covering its global papers was about to be announced.

Sensing a triumph, Frydenberg said the Australian code was “bringing the parties to the table”. It was “leading the world” and would “sustain public interest journalism in this country for years”. He congratulated the digital giants and news media companies for the “good faith” in which they negotiated — only to be blindsided by Zuckerberg on Thursday morning.

That morning Frydenberg rang the Facebook chief for a 30-minute conversation, making clear his disappointment at Facebook’s shutdown and working through Zuckerberg’s concerns. The Facebook chief was not on top of the code’s provisions. While Frydenberg called their talk “constructive” it seems Zuckerberg had trouble stomaching the arbitral mechanism feeding into the code’s potential as a precedent for other nations. “We are going to work through those issues with Facebook,” Frydenberg said.

He said while Google “was always a bit in front”, Facebook had made “a lot of progress” in talks with media companies. Frydenberg said it was clear from his talks with Pichai and Zuckerberg that “they do want to enter into these commercial arrangements”. The rupture with Facebook had come “at the 11th hour”. The government knew that “many Australians rely on Facebook” and “we would like to see them here in Australia”. But, the Treasurer said, Zuckerberg understood that the government “will legislate this code”.

The issue in its own right is hardly momentous — asking Google and Facebook (worth a combined $2.6 trillion) to share revenue from the use of Australian news content. Such lost revenue would not involve tangible financial damage. But it is the precedent that matters with the US, Britain, the EU and Canada studying the Australian model and this power struggle.

“Google and Facebook and other digital giants are very focused on what it means, as far as a precedent goes, for other countries,” Frydenberg said.

“The Australian government makes laws for Australians. And we want the rules of the digital world to replicate the rules of the physical world.”

Morrison was talking tough on Friday: “I would just say to Facebook: this is Australia. You want to do business here, you work according to our rules.

“We’re happy to listen to them on the technical issues of this, just like we listened to Google and came to a sensible arrangement. But the idea of shutting down the sort of sites they did yesterday as some sort of threat — well, I know how Australians react to that.”

Morrison said he had discussed the issue with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and French President Emmanuel Macron. Many nations were moving to regulate big tech and were assessing how to do it.

The key concession Frydenberg has signalled is that if big tech companies enter commercial deals then he could exempt them from designation under the code since designation is the discretion of the Treasurer. Asked about designation, Frydenberg said: “If commercial deals are in place, then it changes the equation.” In short, cut a commercial deal and avoid arbitration.

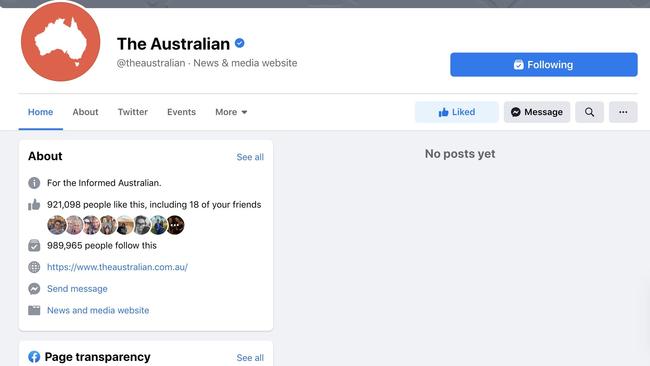

Facebook’s threat must be seen in context. News is still available from multiple sources. Facebook will diminish its own profile by removing news, with Fletcher pointing out this diminishes its brand. With 40 per cent of Australians getting their news from Facebook — just think about it — the shutdown will affect many people. If the shutdown sticks, Facebook “news” will become even more fake and unreliable while people will have an incentive to find alternative news sources.

The statement this week from Facebook Australia’s chief William Easton argued the government’s code was fundamentally unacceptable and drew the distinction between Google and Facebook. Easton said while Google Search was “inextricably linked” with news, publishers willingly posted news on Facebook because “it allows them to sell more subscriptions”.

Easton said: “The value exchange between Facebook and publishers runs in favour of the publishers — which is the reverse of what the legislation would require the arbitrator to assume. Last year Facebook generated approximately 5.1 billion free referrals to Australian publishers worth an estimated $407m.

“For Facebook, the business gain from news is minimal. News makes up less than 4 per cent of the content people see in their News Feed.” Easton said the legislation sought to “punish Facebook for content it didn’t take or ask for”.

Sounds good — but this doesn’t hold water. If Facebook’s argument is correct it has nothing to fear. If it is actually giving more value than receiving then there is no case for the arbitrator to extract cash from Facebook, so nothing to worry about. The real point about news content on Facebook is different — its function is to prolong your time on the platform and prolong your exposure to advertising.

The deeper point is that Facebook is social media. The platform has become the agent of intermediation between the news reader and the news business. Facebook has monetised a role as operating instrument between news consumer and news generator. Zuckerberg must loath the assumptions that underpin the code as it confronts this situation.

Yet Facebook’s retaliation this week also carries a stunning reverse message — you shouldn’t be looking for news on Facebook. The platform is already notorious for its reluctance and inconsistency in meeting its publishing responsibilities: witness live-streaming the Christchurch massacre, tolerating anti-vaccine propaganda and failing to tackle agents of child sexual abuse.

However the real threat from big tech and Facebook runs deeper. As figures from George Soros to Jonathan Haidt have argued, these companies constitute a challenge to human autonomy and social and political life. Haidt has warned about a threat to democracy over the coming generation off the back of social media while Soros has warned about the intersection between authoritarian states and big tech monopolies with their powers of surveillance and state control.

Facebook’s shutdown against Australia this week betrays the absolute contempt of the digital giant for such concerns. It exists as a micro example of what big tech is prepared to do to get its way against a middle-sized democracy. This was an assault on Australia’s civic life. Facebook blocked not just news sites but government, health, pandemic, emergency, community and political pages and information including disability advocacy and suicide prevention. Why did Facebook do this? To intimidate the government in the cause of its financial interests. There was not the slightest pretence of anything else. It used the power because it had the power.

Frydenberg said its action “will damage its reputation here in Australia”. Health Minister Greg Hunt said: “This is an assault on a sovereign nation.” He said the government was “profoundly shocked” that many health sites were blocked during a pandemic. Former ALP leader Bill Shorten told Sky News Facebook had behaved like “thugs and bullies” and warned “the government cannot back down — the rest of the world is watching what we do here.”

This is a power play shootout never seen before. It is a war between Australian sovereignty and global digital monopoly. It pits Australian lawmaking democracy against the big tech “masters of the universe” in the form of Facebook deploying its media power against Australia.