Edna O’Brien’s legacy is bold stories and beautiful writing

Acclaimed and groundbreaking novelist Edna O’Brien conveyed the Irish experience in prose that was spare, luminous and sexually candid.

As Edna O’Brien said on receiving the American Ireland Fund Literary Award in 2000: “A writer must consider the psyche, the soul, the pulse, the danger, the wounds, the sins, the mirth, the sorrows and everything else of one’s country, and then write it in a language as pure and as deep as the place you are writing about.” Long years as an expatriate living in London did not stop O’Brien, who died in July at the age of 93, from setting novel after novel in the land of her birth. She made Ireland, and in particular County Clare, as vivid a presence to her readers as her human characters.

If there was a fine line between this sense of place and the Celtic kitsch of which some accused her, she was often enough on the right side of that line to justify her reputation as one of the most powerful writers of her generation in the English language. Her fierce, direct prose and her lyricism were recognised by a plethora of literary prizes, among them the Writers’ Guild Award for best fiction (1993), the European Prize for Literature (1995) and a lifetime achievement award from Irish PEN, the society for Irish writers (2001).

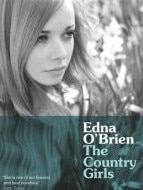

O’Brien’s first novel, The Country Girls – now widely recognised as an Irish classic – outraged public opinion in Ireland when it was published in 1960, given that it dealt with the sexual awakening of two former convent schoolgirls who refused to be bound by conventional morality. When the writer’s mother reported that some of her neighbours had fainted as copies of this book were ceremoniously burnt, O’Brien bravely quipped: “It must have been the smoke.” But she was hurt all the same by the lack of recognition from her family and the wider Irish community for what she had achieved. The book was full of insights, written in a vivid, conversational style, and created characters readers could care about because they were believable human beings: spirited and humorous but flawed, inconsistent and sometimes tragic.

Pronounced “a smear on Irish womanhood” by Ireland’s minister for culture, The Country Girls was nevertheless followed by two more novels about the same girls, Kate and Baba. All three books in succession were placed on the censorship index and banned from sale in Ireland, but the story soon went about that bootleg copies were being avidly read – by torchlight, of course, and under the blankets – in girls’ boarding schools the length and breadth of the country.

To O’Brien’s prudish opponents, the second book of the Country Girls trilogy, The Lonely Girl (1962), made the first seem “a prayer book by comparison” as O’Brien herself acknowledged, but its most powerful scenes are those of social, rather than sexual, intercourse. The most unnerving passage in the book is the beautifully understated, horribly oppressive scene in which Kate’s parish priest tries to talk her out of her relationship, as yet unconsummated, with a divorced man.

In time, O’Brien’s work gained acceptance in Ireland, reaching the top of the bestseller lists, but it was still her Irish critics who were the fiercest. In The Irish Times, Fintan O’Toole castigated her for her “unjustifiable intrusion” upon the private grief caused by a real-life tragedy, which she fictionalised in her novel In the Forest (2002). O’Brien riposted: “Is someone going to say Picasso should not have painted Guernica?”

She was also sometimes lambasted for over-Irishness, and for continuing to write about the Ireland of her youth rather than modern Ireland. She did not live in Ireland full-time after 1959, but returned there regularly, gave a series of public readings there, stayed in the oceanfront house in Donegal designed for her by her son, Sasha Gebler, an architect, never lost her accent and insisted she wanted to be buried there, in her mother’s family grave.

Josephine Edna O’Brien was born on December 15, 1930 into a Roman Catholic family living in Tuamgraney, County Clare. Her father, Michael, a heavy drinker, had inherited a considerable amount of land, but seemingly gave away or squandered much of it – “in archetypal Irish fashion”, according to O’Brien. She grew up in fear of his rages, often retreating to the surrounding fields to daydream and to write stories in which, she later recalled in her memoir, “the words ran away with me”.

Obeying the familiar injunction to writers, “Write what you know”, O’Brien reassembled her father into the tragicomic character of Kate’s father in The Country Girls, a man who, when drunk, would happily swap a 13-acre meadow for “the loveliest greyhound”. In the numerous women she portrayed in her novels as lonely, humiliated and the butt of men, she also provided glimpses of her hardworking, stoical mother, whom she said she “over-loved”.

O’Brien was educated at a public school near her home, and then at the Convent of Mercy, boarding school in neighbouring County Galway. With the help of these two institutions, she said, she was able to add a few fairy stories and tales of heroism to the tally of prayer books, cookery books and bloodstock reports that were all there was to read in her parents’ home, where literature was, at best, viewed with suspicion.

The Bible naturally figured in her upbringing and it is clear her considerable powers of expression must also have grown out of Ireland’s oral tradition – the stories told by, and conversations had with, friends, neighbours and family. As a child she was privy to the world around her, “aware of everyone’s little history, the stuff from which stories and novels are made”.

Although, to her family’s dismay, she had long intended to be a writer, O’Brien pleased her parents when she left school to study pharmacy. It was while working in a chemist’s shop in Dublin that her literary education began in earnest with the purchase of a second-hand copy of TS Eliot’s introduction to the work of James Joyce. She became a Joycean for life, repaying her debt in 1999 by writing a well-received biography of the author of Ulysses, so it was fitting that, in 2006, she should receive the Ulysses Medal from University College Dublin, and that the award ceremony should take place there in a theatre where Joyce himself had attended lectures.

It was also in Dublin that O’Brien met her future husband, Ernest Gebler, an Irish writer of Czech origin whom some years later she metamorphosed into Kate’s sadly incompatible lover, Eugene Gaillard, in The Lonely Girl. Gebler had been married before, was 16 years O’Brien’s senior and a Marxist. Her family thought it a highly unsuitable match, but the couple eloped, married, had two sons, and in 1959 left Ireland for London where, according to O’Brien, she felt for the first time that she could write without being constantly watched and judged.

Her first three novels were written in the space of five years. After The Country Girls and The Lonely Girl came Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964), whose title was doubly ironic because the girls in question were in no way blissful, and 1964 was also the year she and Gebler divorced, at least partly because Gebler seemed to have been unable to reconcile himself to his partner’s instant success at a time when his own writing career was waning. Suggestions made on his behalf that he had actually written her first two books for her were dismissed by O’Brien as “preposterous”. Their sons, Sasha and writer Carlo Gebler, survive her.

Her success was rapid. Within two years of The Lonely Girl appearing in print, she had written the screenplay for a film version, called Girl with Green Eyes, and starring Rita Tushingham as Kate, Lynn Redgrave as Baba and Peter Finch as Gaillard. She also wrote the screenplays for Three Into Two Won’t Go (1969), featuring Rod Steiger and Claire Bloom, and for Zee and Co (1972), with Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Caine. O’Brien, once a country girl herself, was now moving in the circles of the rich and famous.

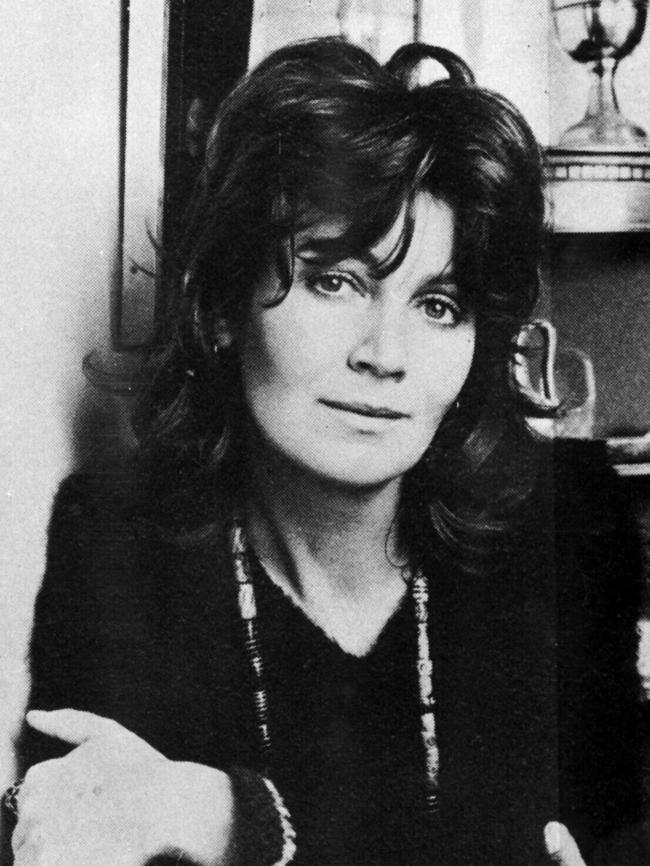

From 1964 she wrote regularly for television, a medium on which, years later, given her striking good looks and original and often controversial views, she was herself to appear to advantage. She appeared on the very first edition of the BBC’s Question Time in 1979, and in the 1980s was seen in the television mini-series of Fay Weldon’s book, The Life and Loves of a She-Devil.

After Girls in their Married Bliss came a flood of novels and short stories, with a book appearing every year or two in the second half of the 1960s and throughout the 1970s. Even in her early to mid-70s, she was writing a novel every four years. At first the recurrent theme was women searching vainly, like Kate and Baba, for fulfilment in their relationships with men. Later, from the 1990s onwards, her women tended to be victims of rather more savage storylines, might even be taken hostage or murdered.

O’Brien stirred up controversy by portraying the human face of terrorism in House of Splendid Isolation (1994), about an elderly woman taken prisoner in her own home by an IRA man on the run. In the same year she offended thousands with a favourable profile of Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams in The New York Times: “Given a different incarnation in a different century,” she wrote, “one could imagine him as one of those monks transcribing the gospels into Gaelic.”

Her increasingly violent storylines reached their apotheosis with In the Forest (2002), a disturbing novel O’Brien described as “hell” to write, based on the real-life crimes of Brendan O’Donnell, who in 1994 abducted and killed a woman and her three-year-old son, and also murdered a priest. O’Brien focused as much on the mental state of the killer, and the abuse and deprivation he had suffered, as on the fate of his female victim. Yet what linked that book and her first was its evidence of her continuing dismay at the parochialism and repressiveness of Irish society. With The Light of Evening (2006), she returned to writing lightly disguised accounts of her family relationships. As she told The New York Times: “An artist keeps going back to very wounded moments.” In this book, a dying woman, reflecting on her unhappy marriage to a hard-drinking horse trainer, is a representation of O’Brien’s mother, while O’Brien herself is the dying woman’s daughter, a writer successful in Britain but considered shocking by her Irish readers.

Red-haired, green-eyed, with finely chiselled features and alabaster skin, O’Brien was considered striking in her youth and still a glamorous figure in her late 70s and 80s, exuding an attention-grabbing mixture of spiritedness, flirtatiousness and bohemian chic. Her regular house parties in Chelsea had drawn the likes of Marlon Brando and Richard Burton. By her own account, her inspiration as a writer often arose from the rush of emotion brought on by a love affair. It seemed she had many beaux, about whom she was mostly highly discreet, but she did let slip to a journalist that she had had “a bit of a romance” with Robert Mitchum, later writing in her 2012 memoir, Country Girl: “We danced all the way up to the bedroom … with all the shyness of besotted strangers in syrupy songs.”

There were also rumours of a longstanding devotion to an unnamed but prominent politician.

O’Brien was beloved of the American literary establishment and won multiple awards including the Los Angeles Times book award in 1990 and the Medal of Honor for Literature of the National Arts Club in New York in 2002. “No one today writes lovelier, more glowing and more mordant English than Edna O’Brien,” said historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. Back in Ireland, in 1999 O’Brien was awarded an honorary doctorate by Queen’s University Belfast, and in 2006 was appointed adjunct professor of English literature at University College Dublin.

Her last novel, Girl (2019), a soul-searing narrative about a Nigerian girl abducted by Boko Haram, stemmed from a newspaper report about a girl found wandering in Sambisa Forest carrying a baby. “It was new territory for me, emotionally, geographically, culturally,” she said, aged 88, after its release. “I had to discard the things that have fortified my writing for 60 years – landscape, lyricism, love … put all those things aside and just dive in as if this was the first book I had ever written.” She made two trips to Nigeria and met several young women who had escaped captivity. “The world is crying out for such stories to be told and I intend to explore them while there is a writing bone left in my body.”

Reflecting on her encroaching mortality, she was sanguine and would think of her “very lovely grave” situated on a holy island on the River Shannon. “It’s my mother’s family grave, but, ironically, she herself is not buried there, because she wanted her grave to be in a village where people passing by would say a prayer for her. Whereas I want the birds … the old monasteries that are ruined, and the lake and just the song of nature.”

Edna O’Brien DBE, novelist, was born on December 15, 1930. She died after a long illness on July 27, 2024, aged 93

The Times