Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian — White House under JFK

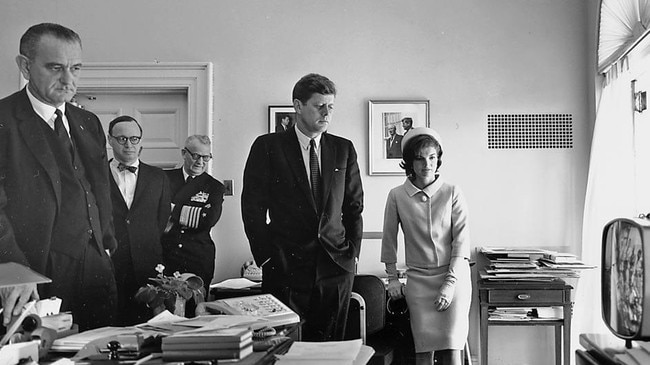

When Arthur Schlesinger began working at the White House there was little doubt why: JFK wanted a historian for Camelot.

When Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr began working at the White House as a roving adviser and speechwriter, there was little doubt what he was really there for. John F. Kennedy wanted a court historian.

In early 1961, Schlesinger wrote a memo for the president noting that a proper history of the Kennedy administration would depend on keeping a thorough record of decisions. He cautioned that any adviser with “a literary glint in his eye” should not consider writing anything without the president’s permission.

Schlesinger told Kennedy he did not see himself working at the White House with a “historical mission”.

He was hoping to return to Harvard and finish his multi-volume The Age of Roosevelt (1957-60), and “unless you wish me to do so” he had no plan to write “The Age of Kennedy”. But, shrewdly, he left the door open. Kennedy set him straight. While the president did not want advisers keeping diaries or notes, Schlesinger was in a different league. “We’d better make sure we have a record over here,” Kennedy told him, “so you go ahead.”

With that instruction, Schlesinger began keeping 8-inch by 4-inch (20cm x 10cm) index cards in his pocket to make notes of important conversations and observations.

In truth, he took a job at the White House because he wanted to witness the exercise of political power. Although he had written masterful books about Franklin Roosevelt and Andrew Jackson, they were not informed by being at the centre of power.

The index cards became the basis of Schlesinger’s magisterial book, A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in The White House, published two years after Kennedy was assassinated. With sparkling prose and penetrating insights, it remains one of the essential books for understanding JFK. It combines firsthand knowledge with scholarship that blends biography, memoir and history.

The book wasa bestseller and earned Schlesinger his second Pulitzer Prize (the first was for the book on Jackson). It was criticised for betraying confidences and cashing in on Kennedy’s memory. It also ignored Kennedy’s infidelity and health problems. But what confounded critics most was the straddling of genres. Was Schlesinger’s credibility as a historian traded for hagiography?

OnDecember 17, 1965, Time put a pastel illustration of Schlesinger on its cover. The headline read: “The Historian as Participant And Vice-Versa”.

The struggle between “the historian” and “the participant” is at the heart of Richard Aldous’s methodically researched and readable biography of the eminent academic, gifted writer, valued counsellor, public intellectual and persistent provocateur. Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian offers an account of his life and a critical examination of his writings.

Aldous makes good use of Schlesinger’s papers, purchased by the New York Public Library after his death in 2007. He also draws on Schlesinger’s letters, diaries and the first volume of his memoir. There are interviews with his two wives and several children.

He was born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger in 1917. His father, Arthur Meier Schlesinger, was a noted historian. The son decided to emulate the father “to escape the misery of his adolescent life”. He changed his name to Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Aldous writes judiciously about Schlesinger’s unhappy schooling, his early academic career and his wartime work in intelligence.

After the war, he returned to Harvard, flush with the success of The Age of Jackson (1945) and The Vital Centre (1949), which argued the virtues of centrist liberal democracy. But he was gravitating towards politics. He worked as a speechwriter on Adlai Stevenson’s ill-fated presidential campaigns in 1952 and 1956. He found Stevenson to be underwhelming: too conservative, often Hamlet-like in his hesitation. While initially sceptical about Kennedy, he joined the winning campaign in 1960.

Aldous shows Schlesinger to be a valued White House adviser and speechwriter with an “easy and informal” relationship with Kennedy. But he was never fully at ease with the Kennedy crowd. He fought a turf war with speechwriter Theodore Sorensen. Kennedy sometimes found him frustrating, for instance, when he complained about the state of the White House tennis court.

In later years, his writings explored multiculturalism, war and the presidency. Schlesinger encouraged Robert Kennedy to run for president in 1968 and was persuaded by his widow, Ethel, to write Robert Kennedy and His Times (1978). He never completed the Roosevelt series, but The Imperial Presidency (1973) was a major work of scholarship when Richard Nixon’s abuses of power were becoming apparent. It is disappointing Aldous covers the last 30 years of Schlesinger’s life in just 25 pages.

Arthur Jr revered Arthur Sr and paid tribute to him by reworking his “cycles of history” theory and relaunching his survey of historians ranking US presidents.

But the son eclipsed the father as “one of the foremost historians of the postwar era”. Few historians attract biographers. But then, few have combined their craft with the study of power, as Schlesinger did.

Troy Bramston is a senior writer on The Australian and is the author of Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader.

Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian

By Richard Aldous

Norton, 486pp, $42.95 (HB)