Diversity, equity and inclusion is out but won’t die quickly in the arts

Universities and cultural establishments are where woke ideology is most deeply entrenched and will be hardest to shift.

To some overexcited observers it is a liberation comparable with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The arcane heraldry of the Progress Pride Flag will be torn from the walls of HR departments, pronouns excised from email signatures and diversity training days summarily cancelled.

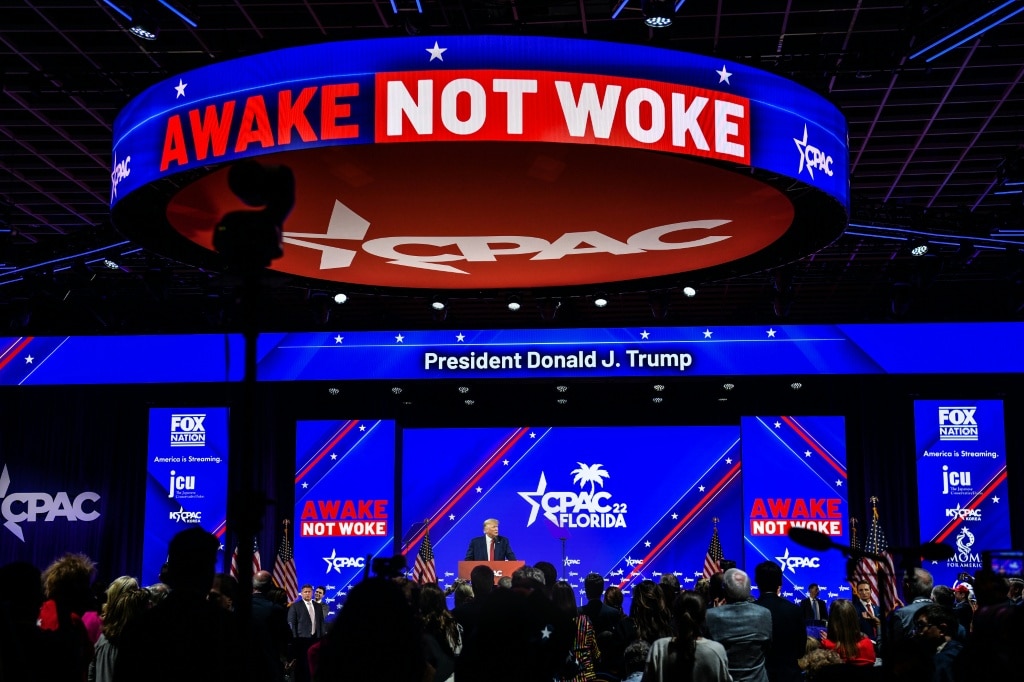

The much-heralded “rollback” of corporate diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in the aftermath of the inauguration of Donald Trump marks, we are told, the “dawn of the anti-woke era” or even the downfall of “the tyranny of woke censorship”.

I agree that an important, broadly welcome and surprisingly rapid social shift is under way. But I am not convinced that the triumph of this counter-reformation is as total as some of its more hopeful enthusiasts imagine. Many adherents of political correctness are as committed as ever. The consequences will be worth watching.

International capitalism’s flirtation with the politics of the student union was always an unlikely one. The affair – passionate, confused, rather mad – had more of the air of an imprudent fling than of a serious commitment.

Clumsy gestures at radical chic by Amazon, General Motors and McDonald’s – who could have predicted a ruthlessly profit-seeking fast food enterprise would end up fostering “healing spaces for black individuals”? – would have delighted and astounded even the term’s cynical inventor, Tom Wolfe. He also would not have been surprised to learn they now are backing away from those ideas.

With hindsight, the phenomenon of “woke capitalism” is becoming more explicable. Anybody who has worked for a large company knows that strange notions and ill-conceived “initiatives” blow through such institutions like rotten autumn leaves through a ruined cottage. Sheer novelty is often a recommendation in itself.

Though many executives were doubtless sincere, I suspect that for some of those now eschewing DEI the term didn’t represent much more than another buzzword in a corporate culture addicted to buzzwords. The upside to not really caring about ideas is that it is relatively easy to slough off the bad ones when you have tired of them.

Nobody at McDonald’s (with the possible exception of a penurious burger-flipping PhD student somewhere) is a committed scholar of American philosopher Judith Butler. But in some sectors, most notably academia and the arts, these ideas are entrenched and sincerely held.

Newly announced reforms to university funding mean institutions failing to promote diversity may face cuts. And the culture of political correctness long precedes the weird fevers of the early 2020s. As long ago as 1992 a hero of mine, art critic Robert Hughes, delivered a lecture warning of a culture of “victimhood” and the “fashion for judging art in political terms”.

There’s a plausible argument that the episode we think of as “the culture war” was only the wider flaring-up of a fire that has been smouldering away in humanities departments for three decades or more.

Friends working in universities report an atmosphere in which it is forever the summer of 2021 – an eerily preserved Miss Havisham’s house of mouldering ideologies and stale doctrine.

Many mediocrities have built careers on simplistic political interpretations of art and lack the talent to think any other way. They shore up their own positions by hiring like-minded people. Meanwhile, many of the “grown-ups” who protected the art galleries and the English departments in their care are drifting off into retirement.

In many places the revolution has been institutionalised. Curriculums have been reformed. Books have been reprinted without their offensive passages. A few years ago, Tate Britain rehung its permanent collection to reflect fashionable sensitivities. Disapproving reminders that the subjects of paintings by George Romney and Thomas Gainsborough “participated in the trade of enslaved people” or “amassed (wealth) through Atlantic trade and plantations” are now part of the permanent story this country tells about its artistic heritage.

In the National Portrait Gallery (also rehung at the height of the woke moment), Samuel Pepys stands condemned to posterity as a sex abuser by the label fixed next to his picture. I sometimes wonder if I will live to see the curator intelligent enough to replace it with one explaining that his diary is one of the all-time wonders of human introspection and that Pepys’s extramarital excursions are not even the 100th most interesting thing in it.

One strand of opinion holds that these organisations have the power to stamp their values on society permanently. But it is worth countenancing another future, in which those institutions still clinging to the fashionable ideas of the 2020s exile themselves from the mainstream and doom themselves to irrelevance as the rest of society simply moves on.

Perhaps they will one day seem like those nearly extinct dissenting churches founded out of doctrinal disputes in the 17th century. At the very least, I think museums and universities will find that rather than leading the way to what briefly seemed as if it might be the mandatory progressive future for all citizens, they have simply picked a side in a society that is growing increasingly polarised.

The corporate retreat from political correctness shows not that it is extinct but that it is no longer the consensus position. A choice, not a default.

Ironically for organisations obsessed with “outreach”, museums and universities may find they are doomed to speak only to a small (probably urban and educated) portion of society.

The precipitate decline in public trust in academia in the US gives a hint of the looming dangers of that path. McDonald’s doesn’t offer many lessons to the arts and education sector but the value of apolitical pragmatism may be one.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout