Earlier this week, Shell PLC apologised to the world for a transaction it made that broke no laws, violated no sanctions and didn’t even represent any new environmental hazard.

The company’s offence was to have purchased last week a few hundred thousand barrels of Russian oil on the open market at a sharp discount. With much of the civilised world, as we must surely call it once again, shunning output from Vladimir Putin’s murderous regime, oil traders were offering deals to anyone who would buy, and Shell’s eagle-eyed team spotted a bargain.

The backlash was fierce. Led by Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba and picked up on social media, a chorus of condemnation shamed the oil major and by Tuesday Ben van Beurden, its chief executive, felt it necessary to issue an abject apology.

Shell’s shaming was a powerful example of a phenomenon that is rapidly reordering the global strategies of big companies in the West. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has accelerated a trend that had begun in the last few years, in which corporations find themselves under increasing pressure to align their business objectives with the prevailing political orthodoxies - and now the geopolitical aims - of the countries where they are headquartered.

As the world evolves once again into two ideological camps, trade (and investment) will again “follow the flag”, to reprise the term that characterised global capitalism in the colonial era, and again during the Cold War, with far-reaching implications not just for national and international economics and politics but for the cultural and social relations between nations.

Shell’s mea culpa was especially noteworthy because it was not driven by official mandate. Even as the company was grovelling to its social media tormentors, the US, the EU and the UK were still permitting the purchase of hundreds of millions of dollars every week of Russian oil and gas on the open market. (The US and Britain announced their bans on Russian oil later that day.)

It was instead an example of “self-sanctioning”, where chief executives have to respond quickly or get ahead of public opinion before opprobrium swamps them. It isn’t too cynical to suggest that companies are not doing this primarily out of an abundance of idealism. As happened with the Black Lives Matter and MeToo campaigns, the need to show you’re on the “virtuous” side of a sudden surge in political sentiment is forcing companies to act to protect their reputations and ultimately their revenues.

“It’s a wake-up call. The risk calculus is now more realistic. They’re not doing this out of patriotism but out of self-interest,” says Peter Navarro, an economist who served in the Trump administration, and who has long been critical of multinational corporations for putting profits ahead of principles.

US companies have been falling over themselves in the last week to publicly abandon Russia. Apple and Starbucks announced the closure of operations there; Netflix, Coca-Cola, Pepsi and others all said Russians will henceforth be deprived of their products. There was no more symbolic image of the new freeze in East-West commercial relations than the spectacle of Muscovites queueing for their last taste of a Big Mac before McDonald’s shuttered its 800 Russian restaurants, an odd bookend to the pictures of lines that formed when it first opened in Moscow at the end of the Cold War.

The sudden isolation of Russia is significant but the really big change is emerging more steadily in China. The Chinese market is exponentially more important for western companies. Twenty per cent (more than dollars 4 billion) of Starbucks’s global sales are in China. In Russia, the coffee shop chain has 130 shops. In China it has more than 5,000.

Should Beijing decide, as many expect it will, to follow Russia’s example and retake Taiwan by force, the bifurcation of the world economy will accelerate dramatically. But even if it doesn’t directly emulate Moscow’s brutality, the process is already well under way. Beijing’s alignment with Russia, made much more problematic for the West by its support for its ally over Ukraine, will increase the already intense pressure on US companies to decouple their global business from China.

Beyond the geopolitics and international economics, the wider human implications of this reversion by companies to Cold War-era trading patterns will be significant. Some critics have railed at the homogenisation of the global human experience represented by the ubiquity of western fast-food, entertainment and luxury goods. But others saw in the commercial colonisation of the world an opportunity to establish deeper cultural ties that might foster mutual understanding and even a more peaceful planet.

For a while after the Cold War, heady optimists touted the “Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention”, as the New York Times columnist Tom Friedman called it. He argued that no two countries that had a McDonald’s had ever gone to war, proof that global integration produced such shared economic interest and human commonalities among populations that they would not let their armies fight each other.

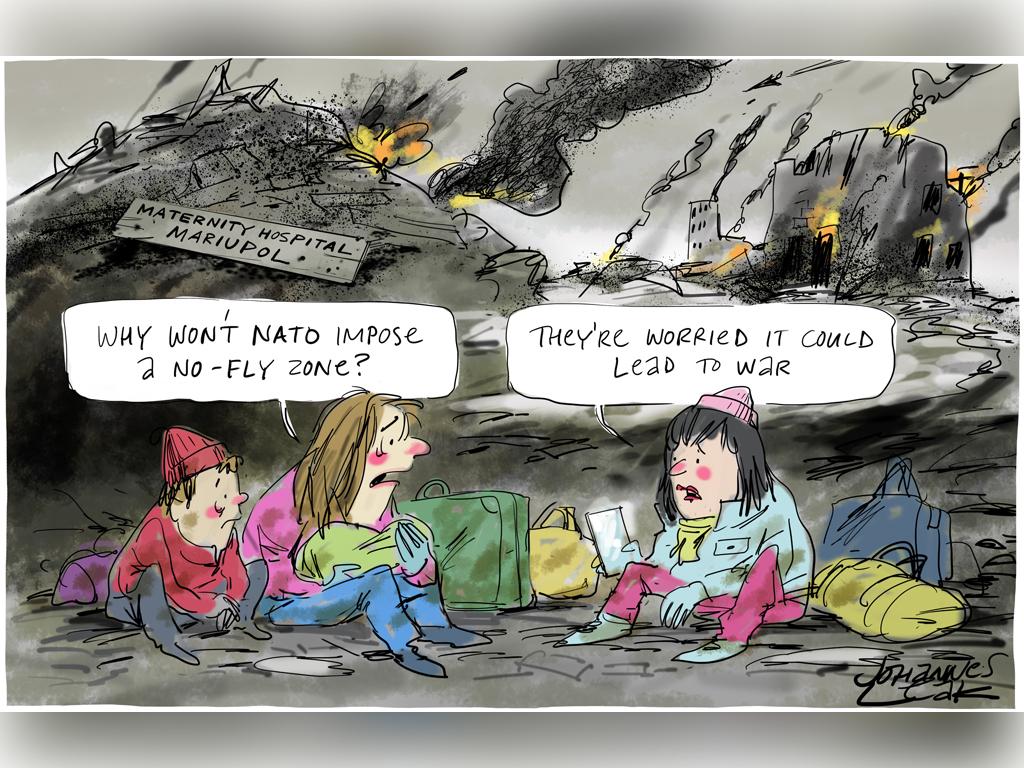

The idea died almost instantly when US jets bombed Belgrade during the Kosovo War in 1999, symbolically smashing the windows of one of the Serbian capital’s McDonald’s. Now that Russian bombs are falling on Ukrainians for whom the Golden Arches have become a familiar feature of the urban landscape, any lasting illusions of a world united by a specious economic assimilation lie completely shattered.

It was a comforting thought for a while that the universal appeal of western capitalism would soften the edges of assertive nationalism. But it turns out that even though Russians like and may well miss their Big Macs and their grande vanilla lattes, the harder realities of national politics and culture will always prevail.

THE TIMES