Coronavirus: I survived 10 days on a ventilator … it was a damned close-run thing

Notes written by nurses helped Roger Boyes to piece together 10 days in ICU as coronavirus ‘moved in for the kill’.

At the fag end of the night shift when backs are bowed with exhaustion, staff nurse Catherine Whitley settled down to write me a letter. “Dear Roger,” she wrote in rounded schoolgirl script, “unfortunately you came to us at handover tonight. You have got a nasty chest infection and you are being supported on one of our ventilators. You are being kept asleep with sedation so your lungs can rest. Apart from keeping you stable and giving you lots of medication I have given you a little wash, cooled you down, brushed your teeth and documented and kept your property safe.”

The nurses at the intensive care unit of St Thomas are encouraged to write entries in a critical care patient diary. When the patient wakes up he or she is left with something that can anchor their memories. If they don’t, well, then they don’t.

At the moment fatality rates for those on ventilators can be 60 per cent. With the help of a dozen professionals huddled around my ICU bed I ended up on the positive side of the ledger but it was a damned close-run thing.

‘I had become the Alien’

Catherine’s entry was for early March. I had been admitted with pneumonia on March 7 and as things got worse — aligned with what would later be an all too common diagnosis of coronavirus — I found myself being transported by stretcher through the underground tunnel system of the hospital. My memory of that moment: a siren blast as we passed by and the faces of unmasked hospital staff jammed against windows staring out at me; I had become the Alien.

Early March in retrospect seems like an extraordinarily complacent time. Children with high fever were being sent blithely home for a stint of self-isolation. We were instructed to sing Happy Birthday twice as we washed our hands. During a strained courtesy visit to the Chinese embassy the staff nervously offered me and a couple of Times colleagues antibacterial hand cream.

‘It began with a cough’

For me it began with a cough in the London Library as I researched a book. Barely enough to disturb the slumber of the members in the leather armchairs of the reading room. There was a gossipy dinner with my thriller-writing mate Adam LeBor in which, he noted, I barely touched my food and he accordingly wiped my plate clean. We wisecracked about Corona novelists. But my breathing was becoming more laboured and my fever was rising.

Being rushed to St Thomas’s was a clarifying moment. For the first time I understood that respiratory disease wasn’t just part of a social parlour game, one that allows men in particular to redistribute their sputum around open plan offices thereby demonstrating their absolute commitment to the workplace. Every year I would get my flu jab, not so much for the public good as to create a holiday bargaining chip, smugly aware that its immunity shield would allow me to skive off for a few days — at about the time that the Cotswolds are at their loveliest — claiming to be under the weather.

Not this time though. The novel coronavirus was real and deadly and it was moving in for the kill. It was still rare, an unwelcome guest from Wuhan, but it meant business.

So my first stroke of luck was a quick diagnosis. St Thomas’s, which had been treating some corona victims since late February, knew what they were looking for and had me down as positive within 24 hours.

‘My lungs collapsed’

But there’s luck and there’s luck. My lungs collapsed. The doctors’ view: it could go either way. I was on a ventilator for ten days. Within hours of being admitted to intensive care my son was being told that everything hinged on my immune system kicking in on time. What was happening was a compression of physical crises, a desperate shuttling between ventilators and the levels of sedation needed to keep the process going, a buying of time while the virus was beaten off. Oxygen tubes were pushed into me, so were the long plastic snakes of feeding tubes. Catheters appeared.

There was a constant monitoring of the other organs: ICU doctors know you have to skate quickly over thin ice. At one point tracheotomy was discussed; for a while I was artificially paralysed. Doctors wondered whether I had also suffered a series of mini-strokes. According to my medical notes I was pumped full of antibiotics and antivirals, including the antimalarial drug remdesivir. My body found itself several times in distress, a critical state that sent it hurtling towards the ICU.

‘You’re merely the battlefield’

You’re rarely a participant in this battle, merely the battlefield. And because of the speed of the enemy advance, civilians get dragged in. On one day my son, Philip, point of contact with the family, was told in the morning that I was stable, then warned that there were limits as to what the doctors could achieve, then told I was in distress, at 2am a missed call from the ward left him frazzled. The next day I was stable again. The medical notes hint at what probably happened — a “respiratory peri-arrest”, a blockage of oxygen to the brain with serious risks of mental impairment. It wasn’t just that the family had to factor in the possibility of a funeral but of me returning as a vegetable.

How the rapidly changing fronts should be communicated has become a source of strain across the system. St Thomas’s has become a magnet for eager young doctors facing what they realise could be the challenge of their generation; they are earning their spurs with back-to-back shifts. The risks they take on willingly because they know they are in the midst of something special and, in their close observation of patients, they are briefly on a par with their elders who have to listen to them.

But what they haven’t been taught is how to deal with the relatives. The result: emotional strain risks burning out an extraordinary talent pool. A model developed by Dr Antonia Field-Smith and Dr Louise Robinson of the palliative care team at West Middlesex hospital guides nurses and junior doctors in how to talk to relatives during the death churn of COVID-19: always share information in small chunks, don’t whitewash the issues, introduce the idea that things might not be going swimmingly. “We hope your dad improves with these treatments but we are worried he may not recover,” again and again you heard these formulas being repeated in St Thomas’s.

The careful choice of words helped the younger staff keep it together but were also a reminder to eavesdroppers like me that we had all become part of an almost unprecedented peacetime turnover of the dead and the dying. Even as a cheerful nursing assistant breezed past the beds singing along to his phone and trilling snippets from Alla Pugacheva’s cheery A Million Roses, there was a sense that we were more than just very sick patients; we had walk-on parts in an end-of-times Fellini movie.

Grief behind a blue curtain

The fans were cranked up to full capacity in the heat of the upper floors of St Tommy’s, all the more so when the man in the neighbouring bed died, his body kept in place to allow the family to grieve behind a blue curtain. An Irish doctor, thoughtfully rather than callously, showed me how to get The Simpsons on the hospital’s TV network when the body was eventually wheeled out. Earphones drowned out the clamour of men talking to the mortuary on radios. This, too, is humane doctoring.

I had never been a patient in a big city hospital before, was unfamiliar with the beeping of machines, the regular policing of blood pressure; the heavy traffic of healing. In the ward after nightfall grown men call out for their mothers.

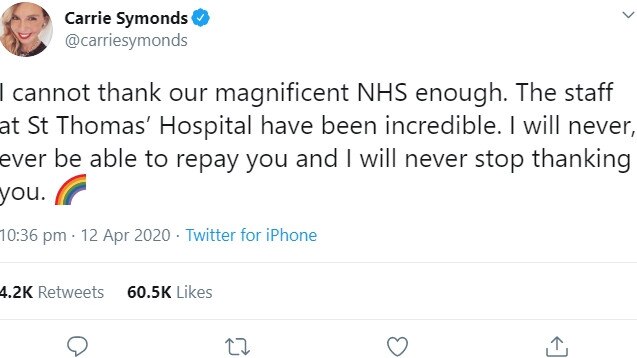

Boris Johnson, on a different floor of the hospital, will have had a gentler experience, which is sad in a way. He was right to thank the nursing staff, of course: they saved his, and my life. But part of the understanding of our modern urban health service is to understand its grittiness, its tensions, its constant improvisations. It is not sleek; it is rugged.

‘Demons of the night’

One patient in the ward seemed to be addicted to a digital game, playing all night, crying with despair when he lost and then voiding his bowels. I say that not to undermine his dignity but to underline: this virus is releasing the demons of the night, exposing not only the misery of disease but also the mental problems of those who ended up there. They too arrived here with little more than a cough.

How does the psyche adjust to a succession of near-death moments? I don’t know yet. A couple of weeks ago I was still under sedation; there’s plenty of work to do. Part of this coronavirus is the presence of delirium. Even my final medical notes released to me this week talk of hallucinations. One shrink says it is down to the brutal shock of the ICU intervention; another blames the sedation; another the side-effects of medication. But whatever the reason, corona comes with a profound disorientation. In the body and brain’s confusion about what is being pumped in, some kind of alternative narrative emerges, perhaps as a safety valve.

Patients have intense dreams as deep as any experience in an opium den. Mine include a conviction that I can recite in great detail. One positions me in a London bakery; another persuaded me that there was a black magic exorcism under way in the hospital. Friends, family and colleagues who talked to me in this period can attest that I was off my head. “You caught the zeitgeist,” says one wry friend, “you are now officially part of the Age of Delirium.”

Hit with the force of a truck

If only it were that simple. What happened was rather more than a parable of our times, an unanchoring from the truth. It’s a disease that does real cognitive damage and leaves survivors like me struggling to explain something that has hit them with the force of a truck. Corona should make us think again about the place of death in life, its random brutalities. At 67, with underlying diabetes and a pretty louche lifestyle, I should have counted on an untidy death. Part of me thought I would end up like my father, pale and silent on the bathroom floor. Instead, some golem jumped on my chest, trying to squeeze the air and life out of me.

I’m still failing cognitive reality tests, simple memory tests that wouldn’t have bothered an infant viewer of Watch With Mother in the 1950s. When a shrink asks me to name months in reverse, my only response is to say: “Why?” This too is coronavirus, part of a mental blockage that endures. The neurologist Oliver Sacks in Awakenings spotted a phenomenon that he called “the stickiness of thought”. As I try to recover my lost weeks I will try to shed this stickiness and work out why I’m still alive.

John Donne talks of a “preternatural birth in returning to life from this sickness”. All of us corona returnees should celebrate our escape, rejoice in the moment — but also think hard about what the hell has just happened to us.

Roger Boyes, The Times’ diplomatic editor, spent several weeks in intensive care at St Thomas’ Hospital in London with COVID-19

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout