Coronavirus Australia: The five weeks that shook the world

On January 24, a little-known water decontamination company with of contracts in China published a salutary warning about the coronavirus.

On January 24, almost a month before the benchmark S&P/ASX 200 index cruised to its record high, a listed but little-known water decontamination company with a bunch of contracts in China published a salutary warning about the coronavirus.

Phoslock Environmental Technologies, chaired and partly-owned by funds management pioneer Laurence Freedman, reassured investors that there had been no impact on the business from the “current health concerns” in China, and staff had completed the first applications of its CSIRO blue-green-algae-busting technology in Wuhan last September and October.

“None of our staff has been affected and there has been no impact on PET’s business,” Phoslock said, in the first virus-related announcement by an ASX-listed company.

The mere mention of an Australian business connection to Wuhan, which is recognised as ground zero for the global spread of the rebadged COVID-19 virus, might have been expected to attract a glimmer of wider interest.

The silence, however, was deafening.

Freedman is understandably circumspect about the source for his COVID-19 call, which turned out to be remarkably prescient.

“We closed our factory (in central-western China) before most people did,” he tells The Weekend Australian.

“The messages we were getting from local authorities were very alarming, and we felt it was necessary to take all necessary precautions.

“The government locked down the Wuhan area shortly after (on January 23).”

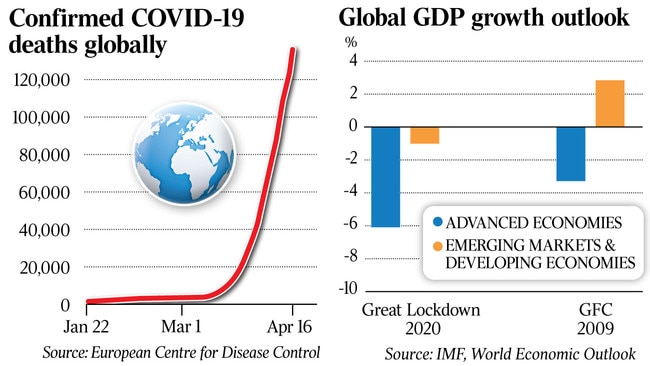

Within a matter of weeks, the rogue virus led to a chaotic run of lockdowns around the world, with income per capita now expected to shrink in more than 170 countries, according to this week’s World Economic Outlook from the International Monetary Fund.

The IMF forecast on Tuesday that $US9 trillion ($14.1 trillion) would be stripped from global GDP over this year and next: more than the combined economies of Germany and Japan.

The forecast 3 per cent contraction in 2020 global GDP — 30 times larger than the 0.1 per cent reduction due to the financial crisis — would be the worst year since the Great Depression, with the Australian economy to shrink by an extraordinary 6.7 per cent this year before staging a recovery in 2021.

As the Russian revolutionary leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin once put it: “There are decades when nothing happens, and there are weeks when decades happen.”

Former Australian Securities Exchange chief executive Elmer Funke Kupper says the collapse in the economy validates the IMF’s comparisons with the Great Depression, but only to a point because the gaping wound is entirely self-inflicted.

It’s a unique situation, he says, and to the extent the crisis is self-made it can also be resolved by “opening the place up”.

“The Great Depression was a decade of misery but this will be nothing like it,” Funke Kupper says.

“Having said that, there are some factors that will make this an uneven recovery.”

As it turned out, COVID-19 claimed no lives at the Phoslock factory in China.

Full production was restored four weeks ago, about two weeks after staff had returned to work.

Freedman says China is back to work “in a very serious manner”, although there were widespread concerns that the virus could produce a second wave.

“But one of the advantages the country has in this kind of environment is that its technology is extremely advanced in facial recognition and keeping tabs on everyone,” he says.

Clearly, liberal democracies would baulk at the scale of China’s intrusions.

On February 1, at the end of the week following Phoslock’s ASX update, Australia reported only a dozen coronavirus cases, all of whom had a Wuhan travel history.

Only one was admitted to intensive care.

While the Department of Health said the exact nature of transmission was “poorly understood”, it seemed there was no cause for immediate alarm.

The ASX 200 closed effortlessly at a record high of 7162.5 points on February 20.

It was the calm before the storm: a once-in-a-lifetime event so vicious and so abrupt that it will fundamentally change how business is conducted for the foreseeable future.

-

Week ending February 29, 2020

COVID-19 cases: 25

ASX 200: 6441.2

Australia awakened to the ruinous financial impact of a global health crisis in the last week of February.

Despite a surge of coronavirus cases in pockets of South Korea, Italy and Iran sparking fears that new fronts were opening up in the battle against the deadly virus, the World Health Organisation declined to label the event a pandemic until March 11. The disease was extended no such courtesy by the equities market, with $210bn, or 10 per cent, stripped from the value of local stocks in five destructive days.

It was the worst week on the ASX since the 2008 financial crisis, and the Australian dollar tumbled to its lowest level in 11 years.

The US, meanwhile, suffered its quickest correction — a market slump of 10 per cent or more — on record, as the Centres for Disease Control spooked investors by warning the country to prepare for a pandemic that could disrupt everyday life.

In an eerie re-run of his fumbling response to the bushfire crisis, Prime Minister Scott Morrison initially failed to grasp the magnitude of what was unfolding before his eyes, insisting that the economic impact of the virus would be greater than the 2008 financial crisis but the underlying economy remained strong.

“There’s a key difference,” he said.

“(The GFC) went to financial stability, financial markets, things of that nature; that’s not what’s at risk here.

“What’s at risk here is the breakdown of supply chains and the flow of people and goods and services because of the health issue.”

Predictably, the market responded by clubbing tourism and travel stocks such as Qantas, Flight Centre and Webjet, which were assessed as the companies most vulnerable to a shutdown of the airline industry and restrictions on people movement.

The market finished the week bloodied and bruised, and the overwhelming assessment was that March would bring no respite.

-

Week ending March 7, 2020

COVID-19 cases: 71

ASX 200: 6216.2

Desperate times call for desperate measures.

So it was on March 3, when the major banks responded to the Prime Minister’s clarion call to pass on the Reserve Bank’s full 25 basis-point cut in the cash rate for the first time in five years.

Westpac led the charge for Team Australia, slashing its variable mortgage rate within a minute of the RBA’s announcement.

The RBA, for its part, became the first central bank apart from the People’s Bank of China to ease monetary policy in response to the coronavirus outbreak, with the benchmark rate cut to a new low of 0.5 per cent.

Governor Philip Lowe said the move was squarely aimed at tackling the economic impact of the coronavirus.

“The coronavirus outbreak overseas is having a significant effect on the Australian economy at present, particularly in the education and travel sectors,” the governor said.

“As a result, GDP growth in the March quarter is likely to be noticeably weaker than earlier expected.”

The hint of a co-ordinated response between the government and the banks to tackle the virus outbreak, and suggestions that the PM might return the favour by ditching his trenchant opposition to a fiscal stimulus package, excited the market.

In a welcome end to a prolonged seven-day rout, the ASX 200 added 0.7 per cent to 6435.7.

The banks were quarantined from the rally as a result of profitability concerns, with lenders unable to lower their rock-bottom deposit rates as an offset to cheaper loans.

As markets basked in a moment of economic sunshine, fears of a deep recession began to escalate.

The PM, who only a week before had effectively ruled out any meaningful debt-funded stimulus program, began a road to Damascus conversion, flagging a “targeted, modest and scalable” package, and then a “targeted, measured and scalable” approach.

The substitution of “measured” for “modest” might have been meaningless in the suburbs, but in Canberra-speak it was momentous.

-

Week ending March 14, 2020

COVID-19 cases: 295

ASX 200: 5539.3

A series of extraordinary events, capped by a record swing in Australian stocks and Morrison’s determination to attend a weekend rugby fixture, punctuated the third week of the crisis.

Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton also confirmed he had the coronavirus, and the federal government delivered on stimulus expectations with a $17bn stimulus package to try to stave off a recession.

The package, which included $6.7bn to boost the cash flow of small and medium-sized businesses so they could pay workers, invest or prepare for the inevitable downturn, came as the market slumped into bear territory after shedding a further 3.6 per cent.

“What the package is all about is keeping Australians in jobs, keeping business in business, and ensuring that the Australian economy and businesses that form that economy bounce back stronger on the other side of this,” the PM said.

On the same day, Reserve Bank governor Guy Debelle confirmed that the controversial central bank measure of quantitative easing, or an unconventional bond-buying stimulus, was under serious consideration.

If Debelle’s commitment was unprecedented, so were the pyrotechnics delivered by the sharemarket on Friday.

After a 9.5 per cent overnight slump in the benchmark S&P 500 index in the US, the ASX 200 sagged more than 8 per cent in sympathy before staging a remarkable rally to close 4.4 per cent higher.

The wild gyrations in all asset classes, including a massive sell-off in bonds, defied the usual pattern.

The arcane rules of asset allocation dictate that bond purchases normally increase when equities go down, leaving the most seasoned investors to wonder if things might be different this time.

As the week closed, Morrison became mired in controversy over his vow to attend a Cronulla Sharks rugby fixture on the weekend, despite health authorities introducing a ban on non-essential mass gatherings from Monday.

The inevitable backflip from the PM’s office came late on Friday.

At Commonwealth Bank, chief executive Matt Comyn made clear his intention not to waste the crisis.

“This is a key moment for the bank and an opportunity to support our nation,” Comyn told staff in an email.

-

Week ending March 21, 2020

COVID-19 cases: 1765

ASX 200: 4816.6

Governments, financial regulators and the banks fired off a battery of bazookas as the nightmare implications of a simultaneous health and economic crisis — with sector closures and social distancing — became apparent.

The crescendo peaked when Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe, who is not known for hyperbole, pledged to do “whatever is necessary” to protect households and businesses from the ravages of the pandemic.

Ten days before, the PM had announced a $17bn stimulus package, equal to about 1 per cent of GDP.

This was now dwarfed by the RBA’s rollout of $105bn of measures, spiced with a further 25 basis-point reduction in the cash rate — the first out-of-cycle rate cut since 1997.

Lowe’s sweeping package featured a $90bn, three-year funding facility at a fixed rate of 0.25 per cent to keep credit flowing to small and medium-sized businesses.

True to its word, the RBA kicked off a program of quantitative easing, or bond-buying, fixing a target rate of 0.25 per cent for three-year Australian government bonds because of their pivotal role in determining many funding rates.

A further $15bn was handed to the Australian Office of Financial Management to invest in wholesale funding markets used by smaller banks and non-bank lenders.

The nation’s banks came to the party, announcing six-month deferrals for interest payable on business and housing loans.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said the $105bn in combined lending measures reflected the government’s determination to do what was required to “support Australian jobs” as the world dealt with the challenges of the coronavirus.

Lowe said Australians were living in “extraordinary and challenging times”, warranting a significant intervention in the financial system.

“To help us get to the other side … we need a bridge,” the governor said.

“Without that bridge, there will be more damage, some of which will be permanent, to the economy and to people’s lives.”

Investors failed to find immediate comfort in the RBA’s landmark package of measures, with heavy selling in bank stocks immediately after the announcement.

The Aussie dollar plunged to its lowest level since 2002.

The markets wanted more, and indeed there was more to come.

-

Week ending March 28, 2020

COVID-19 cases: 4159

ASX 200: 4842.4

The Morrison government was out of the blocks before the week had even begun, demonstrating it now had an accurate measure of the required stimulus and the size of the task before it.

In the second stage of its plan to cushion the impact of the virus, announced on Sunday, the government unveiled a package with $66bn of financial support.

The key feature was a generous JobKeeper wage subsidy program of $1500 a fortnight from March 30, for up to six months.

There was also a loan guarantee scheme for small and medium-sized businesses, featuring a taxpayer guarantee of 50 per cent of new loans issued by eligible lenders up to a total of $20bn.

The value of the government’s entire support package spiked to $189bn, or about 10 per cent of GDP.

While the spike in the deficit will be stupendously large, it was difficult to argue against any of the individual measures.

Former US Federal Reserve boss Ben Bernanke, who oversaw the US response to the 2008 financial crisis, provided some perspective on the scale of the disaster.

“This is a very different animal than the Great Depression,” he said.

“The Great Depression, for one thing, lasted for 12 years, and it came from human problems: monetary and fiscal shocks that hit the system. This has the same feel of panic, some of the feel of volatility.

“It’s really much closer to a snowstorm or natural disaster than it is to a classic 1930s-style depression.”

-

The future

A confounding factor in the Great Lockdown has been the surprise emergence of a technical bull market, hidden inside the COVID-19 economic wreckage.

After a peak-to-trough collapse of 36 per cent, the ASX 200 notched up a 21 per cent gain on Wednesday from its March 23 low.

“The markets don’t know what to do: they go from euphoria to despair on an hourly basis,” respected former fund manager Laurence Freedman says.

Meanwhile, central banks continue to ponder the possibility of additional measures. As ECB President Christine Lagarde put it this week: “Before March, people said to me, ‘The toolbox is empty, you have nothing left, you can’t use the monetary weapon’ - and then we did!”

The reality is that the same lockdown measures that have contained COVID-19 have also opened up a gaping economic hole equivalent to about 20 per cent of GDP.

Further, unlike the 2009 recovery from the financial crisis, there’s nothing to suggest that economic momentum will return in the near future — indeed, quite the opposite.

The implications are deep and wide-ranging.

John Daley, chief executive of the Grattan Institute think tank, says there will be very little passenger traffic between the rest of the world and Australia, apart from countries like China which appear to have eliminated the virus.

Tourism and education accounts for about 4 per cent of the economy, which is large enough to worry about. “We’ll be more keen on Chinese students and correspondingly less keen on students from the US,” Daley says.

“And we’ll have far fewer international tourists but more from China, for the same reason.”

In the same way, less immigration would constrain population growth, making it harder for large corporations to earn a decent return and consigning the housing bubble to a curious historical footnote.

One of Daley’s big concerns is the inevitable spike in unemployment.

“The best case scenario is an orderly, globally synchronised, deep recession, which will take several years to recover from,” he says.

“We know how this story plays out — people spend less and businesses stop investing — and we can use stimulus to reduce the depth and shorten it, but it’s inherently tricky.”

The big idea put forward by Industry Super and IFM Investors chair Greg Combet is a closer partnership between governments and industry funds, which have $700bn in assets under management, to finance the projects that will get Australia working again.

If industry funds were able to generate appropriate risk-adjusted returns, they could partner with debt-burdened governments to deliver sensible infrastructure projects.

“The government procurement processes are time-consuming, so there needs to be a clear set of priorities and the projects have to be investable,” Combet says.

One of the upsides of the crisis is that the banking system has continued to support the real economy, in marked contrast to 2008 when it only made matters worse.

The Financial Stability Board, which advises the G20, has attributed the system’s heightened resilience to the post-financial crisis industry reforms, as it would.

Despite this, former ASX chief Funke Kupper predicts the recovery will be “uneven” for a number of reasons.

For a start, any rush to remove the current restrictions could trigger a second onslaught of the virus, although a rigorous regime of testing and contact tracing could be an appropriate countermeasure.

“If the trade-off is a marginal loss of privacy, I’d pay for it now,” Funke Kupper says.

“Economic activity will also be subdued for some time: people are naturally conservative and will start to save after hoarding products through the crisis.

“Any resumption of normality will require an effective vaccine or treatment.”

The final, significant handbrake would be the accumulation over the last 12 years of an extraordinary $1 trillion in gross federal and state debt, including $500bn in less than 12 months.

“I think our governments have done a terrific job in handling the crisis, but the result is $400bn-$500bn of debt that we can’t afford to have,” Funke Kupper says.

“This can be a catalyst to create a highly competitive economy by embracing reforms that have been gathering dust for far too long — replacing COAG with the national cabinet which has been working so well, reforming an ineffective tax system and creating the right environment for cheap energy.

“Good businesses can also use the crisis to transform the way they operate by digitising processes, changing the way customers interact with the company, and simplifying decision-making processes.

“It’s an enormous opportunity that arrives once in a generation. Let’s not waste it.”

In the shorter term, Funke Kupper is tracking the market’s gyrations, waiting for the buying opportunity that reflects his assessment of the way events are likely to play out.

He expects a deep downturn followed by a muted recovery until the arrival of a vaccine or treatment. “Most bear markets have a temporary recovery but then start to decline again,” he says.

“I still think the markets are too optimistic about how this disease can be managed and how quickly things will recover.

“If there’s a renewed downward shift in the next couple of weeks, it would be a good time to ‘average in’.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout