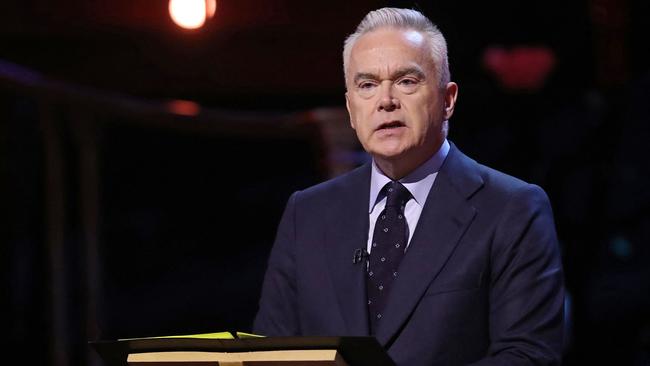

BBC journalists’ fury at handling of Huw Edwards scandal

One of the UK’s top news anchors was allowed to leave the BBC on his own terms despite the charges against him.

The party to toast the retirement of the BBC’s acting chairwoman Dame Elan Closs Stephens was a relaxed affair. It was late January and the corporation’s bosses were gathered in the wood-panelled council chamber of Broadcasting House, central London, for canapes and drinks. There was a funny video about Closs Stephens, and Tim Davie, the director-general, gave a speech.

But four people in the room – Davie, Closs Stephens, Deborah Turness, the chief executive of BBC News, and the senior independent director, Sir Nicholas Serota – were harbouring a dark secret from their colleagues. They knew that Huw Edwards, once the corporation’s most trusted news anchor, had been arrested 11 weeks earlier on suspicion of viewing images of child sexual abuse.

The rest of the country would only discover this last Monday – as did other BBC board members, who were blindsided when they saw it on the news – two days before Edwards, 62, appeared at Westminster Magistrates’ Court.

The man who told the nation of the death of Queen Elizabeth less than two years earlier, pleaded guilty to three charges of making indecent images of children.

Outside court, the former lead presenter of News at Ten had looked defiant in his sunglasses; in court, standing behind a glass screen, he avoided making eye contact with reporters.

It is hard to imagine a bigger fall from grace. His coverage of the Queen’s death, which one former colleague said had made him “unsackable”, is unlikely to be broadcast again and he is being expunged from parts of the BBC archive. Shock among his former colleagues turned into fury at the BBC’s handling of the crisis, especially that Edwards, whose annual salary was more than £475,000 ($934,000), was paid £200,000 ($393,000) in the five months after the police told the corporation of his arrest, and that he was allowed to leave on his own terms in April, when the BBC statement cited medical advice.

One journalist in Broadcasting House said it would be “impossible to overstate the rage” among her colleagues.

“It’s always the same few men being protected, but if an ordinary member of staff ran into half the trouble Huw did, they’d be toast,” a BBC presenter said.

“They create these egotistical presenters who think they will never come a cropper … and flaccid BBC management, yet again, aren’t on the front foot. They are paid huge sums of money yet never do the difficult thing, ending up in yet another crisis. They say they can’t be held responsible for someone else’s actions, but the reason they are paid so much public money is to maintain the trust and transparency that they expect from us as staff.”

A former BBC correspondent compared Edwards to a deposed king: “If BBC News was its own country, Huw’s face would be on its stamps”.

“It talks to the toxic relationship between the so-called talent and the senior managers who let him go with a dignity he didn’t deserve … what you always find with these scandals is that there were red flags that were ignored or summarily investigated and then dropped,” they said.

Those red flags will now be scrutinised. The Sunday Times reported that the BBC was paying for therapy for a woman who made two complaints about Edwards to the corporation, in May 2021, and again in January 2022. Both times, the woman – a member of the public called Rachel, then in her forties – retracted her complaints, but the BBC nevertheless warned Edwards about his online conduct and told him to cease contact, which he did not.

The first time she contacted the BBC, Edwards’ manager told him within hours that a complaint had been made and while Edwards was not told who had reported him, the corporation later acknowledged that Rachel “would have been identifiable” to him.

Rachel alleges that Edwards then called her to pressurise her into retracting the complaint, with emails between the pair showing Edwards appearing to dictate her responses to the BBC. This pattern was repeated with her second complaint seven months later, when she also told the BBC that Edwards pressured her into retracting the first complaint.

A BBC manager met Edwards on February 23, 2022, and warned him to stop contact, but the correspondence continued until Edwards was taken off the air last year. The BBC investigated its handling of Rachel’s complaint, and in a summary of its findings, admitted it “could have” warned Edwards “more formally”.

Rachel and Edwards, who have never met, struck up a friendship after she messaged him on Instagram in 2018. Rachel initially said she feared she was being “catfished” by someone posing as the newsreader, as it “could not possibly be the great Huw Edwards”, so she asked him to wear a pink tie one night to read the news. He later messaged her saying that “the tie was for you”.

Rachel first contacted the BBC three years ago to halt the relationship as she alleges it was becoming “toxic”, as he refused to meet her and would become angry. She says she was struggling mentally and was not strong enough to end the relationship herself. She twice asked him to cease contact, including by blocking her, but he declined and they continued messaging.

Before she retracted her first complaint, Rachel handed the BBC a tranche of messages between the pair which included explicit images she had voluntarily sent Edwards. She felt he encouraged these by taking screenshots, reacting with gratitude and giving her the sexually suggestive nickname “KitKat”.

Before she learnt of his arrest, Rachel messaged Edwards and was warned to cease contact by his lawyers. His lawyers previously said Edwards was unable to comment on these “unsubstantiated” allegations.

The BBC agreed this year to pay for Rachel to receive therapy and last week indicated it would fund 12 further sessions.

In July 2023, reporting on Edwards’ behaviour led to him being suspended. The Sun initially reported that an unnamed BBC personality had been accused of paying a young person who had a drug addiction, and receiving explicit photos from them; their worried parents had contacted the newspaper. A social media witch-hunt ensued and other BBC presenters were falsely accused.

Edwards’ wife, TV producer Vicky Flind, revealed that he was the presenter in question, and said he had been admitted to hospital over mental health concerns.

On Saturday, the young man at the centre of The Sun’s story, who was a teenager when they and Edwards first had contact, told the Mirror that they felt Edwards had “groomed” them. They had initially defended the newsreader.

The Sun’s story meant BBC journalists had to report on one of their most famous colleagues. Sources in the newsroom at the time said some staff, including Newsnight lead presenter Victoria Derbyshire, had done some cursory digging on Edwards before the story broke, amid rumours of his workplace impropriety.

Among the allegations the BBC later reported was the claim that Edwards had messaged three young employees in a way that made them uncomfortable.

Much support was then on Edwards’ side, as many felt that he merely had a messy private life. Edwards is understood to have spoken to some of the BBC’s rivals in the hope that he could rebuild his career elsewhere.

On Friday, the BBC revealed that when Edwards resigned in April he was subject to a “confidential disciplinary process”. Some of those who spoke to the internal investigation had since expressed their upset that the findings were never made public.

“It’s ridiculous that it remains shrouded in mystery,” said a BBC journalist. “We thought that report would never see the light of day. Now it should be a much bigger inquiry. He mentored young journalists and did the BBC’s School Report [a scheme to encourage children to consider a career in TV], so the BBC was giving him access to young people. They should have given him an ultimatum in November: resign or be fired.”

A source said they felt Edwards’s lawyers were slowing down the fact-finding process, making it more difficult for the BBC. The corporation said: “We fully appreciate the complexities and confidentiality of this work can be frustrating for those who have come forward”.

Last week, Davie defended not sacking Edwards in November. “The police came to us and gave us information that they had arrested Mr Edwards, but they wanted to be assured of total confidence,” he said. “We considered it extremely carefully. When someone is arrested, there’s no charges. Also, [there] were very significant duty of care considerations. It was right for us to say, ‘Look, we’ll let the police do their business and when charges happen we will act’.”

Former colleagues of Edwards said he had been long spiralling out of control. “People felt he was taking risks and that he was becoming a megalomaniac and there were rumblings … about him sending messages to young staff,” said one.

In recent years he was known to be unhappy at the BBC and complained when he was overlooked for jobs including leading the 2017 general election coverage, and chairing Question Time.

Much of the anger within the BBC stems from the degree to which management defended him. Before his arrest, the then culture secretary, Lucy Frazer, called in Davie and Closs Stephens. A source said the latter “was very sensitive to Huw’s mental condition”.

Closs Stephens said: “I was informed of Huw Edwards’s arrest in my role as acting chair. I wasn’t aware of the terrible details that have come to light this week”.

Senior BBC insiders have predicted that “Teflon Tim” will survive, emphasising there was no “smoking gun” suggesting that Davie was aware of allegations of Edwards’s improper behaviour to colleagues, let alone of anything criminal. Many, though, are engaging in soul-searching. One journalist who had been friendly with Edwards said: “When that Sun story broke, we all knew it was him. What does that tell you?”

The Sunday Times