Will Russia use nuclear weapons? Vladimir Putin’s options explained

As Moscow threatens to respond to Ukraine’s use of long-range missiles, experts warn Vladimir Putin’s state of mind is the danger that could lead him to going for the nuclear option.

Russia’s nuclear doctrine is the set of rules that Moscow imposes on itself for the use of nuclear weapons.

It states that the Kremlin can use its vast nuclear arsenal in response to any aggression that poses “a critical threat” to Russia’s sovereignty or territorial integrity. This open-ended criterion was introduced on November 19 in an update signed off by President Putin two days after the US announced that it would relax restrictions on Ukraine’s use of its long-range weaponry.

The previous version of the doctrine placed the bar for nuclear retaliation far higher, allowing it only if the existence of the Russian state was under threat.

With clear reference to Ukraine and its western allies, the revision also stated that an attack with conventional missiles, drones or other aircraft by a non-nuclear state that is supported by a nuclear-armed one could meet the criteria for a nuclear response.

Belarus is also brought under Russia’s nuclear umbrella by the update.

Hardliners in Moscow had long urged Putin to lower Russia’s threshold for the use of nuclear missiles in response to the west’s military and financial support for Kyiv — Ukrainians have used British and French-supplied Storm Shadow missiles to strike the headquarters of Russia’s Black Sea fleet in occupied Crimea.

The tipping point, however, appears to have been President Biden’s decision — after many months of vacillation — to grant Ukrainians the use of American ATACMS missiles to strike deep into Russian territory. Putin has said that such a move would mean NATO was “at war” with Russia.

After many months of unfulfilled warnings the updated doctrine runs the risk of being seen by western leaders as another hollow threat. Gradually, the West has probed at Putin’s red lines and found them traversable.

The Russian dictator warned on the first day of the war that any attempts to interfere would result in consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history”. Since then, the West has provided more than $100 billion in aid to Ukraine, as well as deepening military assistance.

Nevertheless, the move represents a significant shift in Russia’s nuclear policy and creates far greater room for interpretation in deciding what constitutes an attack on the nation’s “sovereignty or territorial integrity”. Putin did not consider the Ukrainian invasion of the Kursk region, for example, to be an existential threat to Russia or his regime and yet apparently believes that ATACMS strikes on Russian territory could be.

Has the Russian threat to use nuclear weapons grown?

Russia has said it has moved some of its nuclear missiles to Belarus and has increased an already sizeable military presence in its Baltic exclave, Kaliningrad. That provoked neighbouring Poland to announce it is willing to host NATO nuclear weapons. Putin said Russia’s updated nuclear doctrine would extend the Kremlin’s nuclear umbrella to Belarus, its biggest ally.

Putin has boasted that Russia’s nuclear capabilities are more advanced than America’s and that “weapons exist in order to use them”. He has also warned that the presence of NATO troops in Ukraine could trigger a nuclear war. No NATO member state has so far deployed forces to Ukraine.

There was a setback for Russia’s nuclear forces in September when an intercontinental ballistic missile that Putin once called unstoppable blew up in its silo during a test launch. The RS-28 Sarmat, known in the West as Satan II, was one of several “superweapons” unveiled by Putin in 2018. Satellite images showed a crater about 60m wide at the launch silo at the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northern Russia.

Although President Biden has previously said that Russia’s nuclear threats are credible, Putin’s constant sabre-rattling without action has blunted the effect of his rhetoric. NATO has repeatedly said there are no signs that Russia is preparing to unleash its nuclear arsenal.

Warnings by officials in Moscow of nuclear war, particularly by Dmitry Medvedev, the former prime minister and president who is now deputy head of Russia’s national security council, are generally viewed in the West as aimed at discouraging NATO’s support for Ukraine rather than as serious threats.

Yet Washington remains wary of escalation. “We’re always going to be concerned about the potential for the aggression in Ukraine to lead to escalation on the European continent,” John Kirby, the White House national security adviser, said in August.

In November it was reported that former British prime minister Liz Truss was so concerned in October 2022 that Putin would launch a nuclear strike that officials, in the dying days of her premiership, were examining weather maps and preparing for UK radiation cases.

Perhaps the most difficult question for western governments is trying to guess — or second-guess — what is in Putin’s mind. Rhetoric around nuclear weapons has become so routine in Russia in recent years that it could potentially lower the psychological threshold for their use. There are also concerns over Putin’s state of mind. Gleb Pavlovsky, a Kremlin adviser until 2011, who died last year, told The Sunday Times after the start of the war in Ukraine that the Russian leader’s mental state had deteriorated over his years in power and he was now “reacting to the pictures in his own head”.

Why would Putin ever consider resorting to nuclear weapons?

With the prospect of a never-ending conflict, Putin, who has sole command of Russia’s giant stockpile of tactical nuclear bombs and missiles, could come to the conclusion that only a mighty blow, using the deadliest weapon at his disposal, would save his nation from humiliation and ignominy.

In Putin’s mind, a serious threat to his regime, rather than to Russia itself, may be enough to trigger the use of nuclear weapons against Ukraine or the West.

Putin will mark 25 years in power on New Year’s Eve and his allies have portrayed him as the living embodiment of Russia. “If there is Putin, there is Russia. If there is no Putin, there is no Russia,” Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of parliament, has said.

From a western standpoint, the use of nuclear weapons by Russia would make little sense. Tactical nuclear weapons, with their more limited range and potency, would be devastating but would not guarantee an end to the war or an instant victory for Putin. The use of strategic nuclear weapons, which can level entire cities, would almost certainly provoke a massive response from the West, if not a Third World War. Putin may be unconcerned about destroying the lives of Ukrainian civilians, but would he really be ready to condemn his young children, whose existence was revealed this month, to spending decades in a nuclear shelter in the depths of Siberia?

For Putin, however, using nuclear weapons could be his way of throwing down the gauntlet to the West, his message being: “With you continuing to arm Kyiv with increasingly advanced weaponry to hurt Russian forces, I had no other choice.”

Leaked military files obtained by the Financial Times in February revealed that Russia has drawn up plans for the use of tactical nuclear weapons during the early stages of a conflict with a major power as part of a strategy of “fear inducement”.

The documents outlined hypothetical scenarios in which Russia would respond with nuclear strikes in the event of an invasion, as well as potential conditions to achieve a number of more offensive goals such as “containing states from using aggression … or escalating military conflicts”, “stopping aggression”, and making Russia’s navy “more effective”.

The cache of 29 secret files, drawn up between 2008 and 2014, a time when Putin served as either Russian president or prime minister, are still said to be relevant to Moscow’s current military doctrine and outline a threshold for the use of tactical nuclear weapons far lower than officials have ever publicly admitted.

The low threshold conforms with a doctrine described by Moscow as “fear inducement”, by which it would seek to end a conflict swiftly by shocking the enemy in negotiation with the early use of a small nuclear weapon.

What is stopping Putin from using tactical nuclear weapons?

There are two principal reasons: the first is China. President Xi has publicly stated and, no doubt privately warned Putin in person, that nuclear weapons should never be used.

China is Russia’s strategic partner. The alliance between the two nations has grown exponentially since the war in Ukraine began. The Chinese leader has never condemned his Russian friend for invading Ukraine but, so far, he has not offered military help. Furthermore, he is trying to position himself as a peacemaker, attempting to forge a settlement that would bring a diplomatic end to the war and boost his own reputation and power on the global stage.

Putin will know that if he orders a nuclear strike, however limited, his partnership with China would be put at grave risk, if not destroyed.

Intriguingly, the secret documents referred to above reveal Moscow’s deep-seated suspicion of China and describe hypothetical scenarios in which Russia would respond with nuclear strikes in the event of an invasion by Beijing. Though the two nations have become close allies in the years since the plans were written, with Chinese financial support helping Moscow to weather the storm of western sanctions precipitated by the war in Ukraine, Russia has continued to build up its eastern defences.

One exercise outlining a hypothetical attack by China notes that Russia, referred to as the “Northern Federation” for the purpose of the war game, could respond with a tactical nuclear strike in order to stop “the South” from advancing with a second wave of invading forces.

“The order has been given by the commander-in-chief … to use nuclear weapons … in the event the enemy deploys second-echelon units and the South threatens to attack further in the direction of the main strike,” the document said.

The second reason is the likely response from the United States and NATO. Putin may argue the case in his mind that the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine would not lead to a nuclear or conventional counterstroke by the West because Kyiv is not yet a member of the western alliance and is therefore not covered by Article 5 of the organisation’s founding treaty. This guarantees that an attack on an individual member of the alliance is equivalent to an attack on NATO as a whole.

However, the US has made it clear that the use of nuclear weapons by Putin in Ukraine would have “catastrophic consequences” for Russia. What these consequences would be have not been spelt out. But could it lead to a direct confrontation between NATO and Russia? Putin has to take this possible scenario into account before gambling on his nuclear options.

Has anything changed?

The relaxation of restrictions on the use of ATACMS is just the latest in a long sequence of growing military assistance from the West. The scale and quality of the weaponry provided by the US-led coalition of 50 countries has dramatically increased Ukraine’s firepower. American F-16 fighter jets have already taken to the skies, while Kyiv has used powerful American missiles against Putin’s forces, including against Russian troops massed in border regions.

However, the election of Donald Trump in the US may well have brought about an end to the seemingly infinite stream of arms provision. The president-elect has said he will end the war within a day of entering the White House, with some suggesting that he may force Zelensky to the negotiating table by threatening to cut off all US aid.

Trump has frequently attacked NATO, saying that he would be prepared to let Russia do “whatever the hell they want” to member states that do not meet spending commitments.

Last year, as if in preparation for a possible nuclear attack, Putin sent the first batch of tactical systems to Belarus, his friendly neighbour. It was the first time Moscow had deployed nuclear missiles outside Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Will Russia put nuclear weapons in space?

As focus perhaps shifts away from the immediate threat of a battlefield nuclear detonation, there are growing concerns that Putin may be already considering putting a nuclear device into earth’s orbit.

Putin has a deep interest in super weapons, demonstrated by his public enthusiasm for hypersonic missiles as well as nuclear-armed cruise missiles and torpedoes with allegedly unlimited range.

Placing nuclear devices into orbit, potentially targeting America’s satellite systems, would be the latest example of Russia’s growing aggressive capabilities and would transform space into a new battlefield domain.

It would force the US to develop and deploy new space-based countermeasures, adding another dangerous ingredient to the big-power arms race.

Russia, China, North Korea and Iran are all investing heavily in space-related capabilities, especially anti-satellite weapons, posing a grave threat to America’s global satellite communications network upon which all branches of the US military depend for navigation, precision strikes and command and control.

Launching nuclear weapons into orbit would be a gross violation of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, signed by Russia. Among other agreed principles, the treaty bans the placing of nuclear weapons “or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies or stationing them in outer space”.

What are Russia’s current nuclear capabilities?

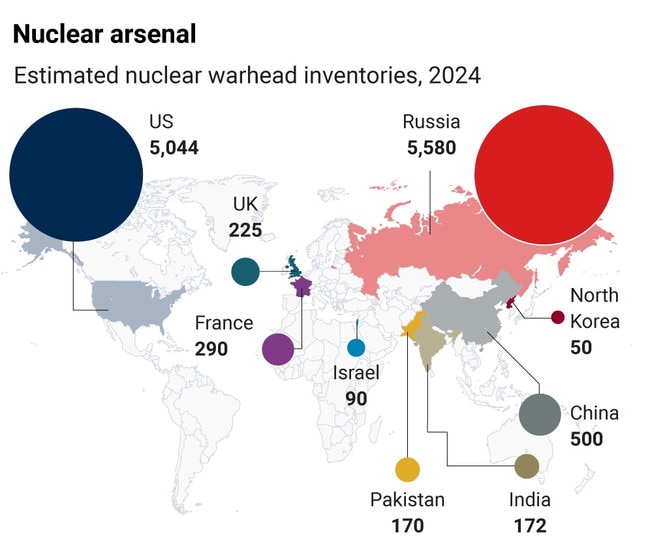

Russia’s nuclear capability is still formidable, despite being signatories to various arms control treaties since the end of the Cold War. Moscow has the world’s biggest nuclear arsenal with 5,580 nuclear warheads, according to the Federation of American Scientists.

Some are so-called tactical nuclear weapons, for use on the battlefield, while others are designed to destroy entire cities.

Putin said in 2023 that Russia would abandon its last remaining nuclear arms control treaty with the US, the New Start treaty, which limited the number and deployment of long-range nuclear missiles, warheads and launch platforms by both sides.

It was the last remaining arms control agreement between Moscow and Washington after President Trump pulled out of a treaty over intermediate range weapons, citing Russian violations. Putin’s suspension of Russia’s participation does not rule out its return to the agreement, which expires in 2026. However, the Kremlin has said there can be no talks on a new nuclear deal while NATO is supplying weapons to Ukraine.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout