Anita Pallenberg and Mick Jagger – at last her children tell the truth

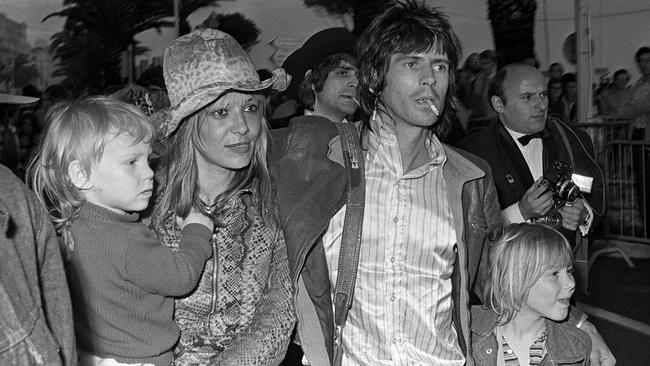

The wife of two of the Rolling Stones – Brian Jones and then Keith Richards – personified 1960s excess. Now her children want to correct the record.

Narrated by Scarlett Johansson, Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg begins with a declaration: “I’ve been called a witch, a slut, a murderer.” The documentary, a project initiated by Pallenberg’s children, is an attempt to change the story. And telling it in her words also finally clarifies the true nature of the relationship between Pallenberg and Mick Jagger.

Pallenberg, who was married to Brian Jones for two years, then to Keith Richards for 13, made the Rolling Stones, Britain’s premier bad boys, seem like a bunch of preening youths by comparison.

Richards says of his former partner, also the mother of his two eldest children, Marlon and Angela: “She scared the pants off me.”

Alexis Bloom and Svetlana Zill’s engrossing documentary uses hitherto unseen footage of Pallenberg and Richards cavorting around the world that Marlon discovered after her death in 2017 and draws on her unpublished memoir.

“Highly intelligent, spoke four or five languages, but had a lack of self-worth that came about from being attractive and belittled constantly for it,” Marlon, 54, says on being asked to describe his mother. “When she was 14 the philosophy teacher at her nunnery in Rome fell madly in love with her, so the nuns kicked her out. She was sent to a boarding school in Bavaria and nobody told her why. From there her options were: model, actor, wife, prostitute. She would have been happier being an archaeologist.”

Marlon is a loquacious, energetic figure, pacing from window to table and back with a cigarette, when we meet at his daughter Ella’s flat in Kensington, west London, to talk about how the film came about.

“In 2012 my father was in town, doing some gig at the O2,” he says. “Anita turned up with a shopping bag with all the Super-8 footage – and my father walked out with it. Typical of him: he thinks everything is his. Anita was, like, ‘That belongs to me and Marlon.’ ”

In 2019, two years after her death, the family was clearing Pallenberg’s cluttered flat on Chelsea Embankment when Ella, a model, came across a manuscript.

“Then my son found a shoebox filled with taped interviews, and it turned out that when we lived in New York in the ’90s, and Anita was babysitting my children, she was going off to do interviews with the writers Lenny Kaye and Victor Bockris. I went through them and they were full of heartbreak and regret, which she never voiced when she was alive.”

Marlon contacted Bloom, who produced Bright Lights: Starring Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds, and Zill, who has worked on documentaries with Alex Gibney, Errol Morris and Morgan Spurlock. “Anita’s children never wanted a hagiography,” Zill says. “Marlon was clear: he wanted all sides of her.”

“I wasn’t a Stones fan, hadn’t read Keith’s book (Life), didn’t know much about Anita, to be honest,” Bloom adds. “But after meeting Marlon I realised: Anita is the really interesting person in the story.” All agree that the tale revolves around a woman who, born in 1942 and being German and Italian, faced a complicated legacy from World War II. She had to be tough and forward-looking to be accepted.

“My grandfather on my mother’s side was a diplomat for the Reich, involved in the Hitler-Mussolini pact,” Marlon says. “There was a similarity between Anita and Yoko Ono, not just for their otherness but because, for the English, they were the enemy.” “She was physically intimidating: devastatingly beautiful and like a tornado,” Bloom says. “Marianne Faithfull said Anita had a carnivorous smile, like you might be her snack.”

Angela Richards says of her mother: “If she liked you, you were her friend. If she didn’t, she would make it quite clear.”

By the time Marlon was born in 1969, his parents were not just world famous but notorious, with Pallenberg being viewed, not least by Keith’s mother, Doris, as a dangerous, exotic influence.

Marlon’s earliest years were spent at Villa Nellcote, a mansion of notorious decadence in the south of France where the Stones recorded much of their louche 1972 masterpiece Exile on Main St. After that, Pallenberg and Keith, facing drugs charges, moved a lot. As a child, Marlon learnt it was his job to clear away the paraphernalia whenever the police turned up.

“For a while we lived in Blakes hotel (in Kensington) because they thought our house in Cheyne Walk (in nearby Chelsea) was bugged,” says Marlon, who has three children with his wife, Lucie de la Falaise, a former model and Yves Saint Laurent muse. “We had houses all over the place, but we never stayed in them: constantly moving, never more than three months in one place.

“The impact is that I never wanted their lifestyle, particularly not for my children. I wanted a normal family, a place in the country.”

He achieved his goal: Marlon and Lucie live in a farmhouse in Kent. Staying for the most part out of the limelight, he works as a graphic designer, photographer and, now, film producer. By the end of the 1960s, after scene-stealing roles in Roger Vadim’s sci-fi fantasy Barbarella and Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell’s cult crime drama Performance, Pallenberg’s profile was as high as Keith’s. Performance involved explicit love scenes between her and Jagger. It has long been suspected that the two also were having an affair at the time – which inspired Richards to write the Stones’ masterpiece Gimme Shelter. Catching Fire at last confirms this. “The funny thing is I never fancied Mick at all,” Pallenberg says in her memoir, as spoken by Johansson’s narrator. “But spend eight hours in a bed together and what do you expect?”

In the Villa Nellcote days Pallenberg was the reigning queen, not least because she was the only person who spoke several languages and could get things done, deciding who got to enter the gilded world of the Stones. But as the band transformed into a stadium-filling, Lear jet-hopping, sponsorship-embracing rock corporation she was increasingly sidelined, not least because Keith disapproved of his wife’s career and wanted her to be a stay-at-home mum.

“You can’t take Dartford out of the boy, can you?” his son says. “He didn’t even want her to do Barbarella. Keith is very traditional in lots of ways and that’s what sent her off the deep end: being stuck at home.” Keith does contribute to the documentary, talking fondly, and with sadness, about Pallenberg. “He is an emotional man, very sensitive, and he agreed to talk about her with no holds barred.”

Were other Stones approached? “I wouldn’t dare. A couple of years ago my daughter had a party and Mick was there – hello, lots of young blonde totty, here comes Mick – and he was supportive of the idea, which was enough. I didn’t need him in it.”

The film takes a tragic turn after it reaches the point when Pallenberg was marginalised by the Stones. In 1976, while she and Keith were living in Geneva, their son Tara died in his cot at 10 weeks old. Marlon was on tour with Keith at the time and Doris stepped in to take custody of their four-year-old daughter, Angela.

“By then she was at a very low ebb,” Marlon says. “The Stones no longer wanted powerful women like Anita giving them shit on the road, so they kept it simple with groupies. I was six and went on tour with Keith, during which I remember being very concerned with his mortality, having seen enough ODs of people who were either shuffled out of the door or, if they did survive, pumped with coffee and cocaine. I would sleep next to Keith and have my hand on his pulse. We were in Paris when Anita turned up after my brother died and I was outside the hotel room with the nanny, listening to this extreme screaming. Then Keith went on stage – that night. It was the ‘show must go on’ attitude of his generation, but my mother was left with no support.”

Then, on July 20, 1979, a 17-year-old boy called Scott Cantrell shot himself in the head while in bed with Pallenberg at her house in Salem, upstate New York. Marlon heard the gun go off. He was nine.

“The boy was working on the grounds and she took him as a lover, to a degree,” he remembers. “I didn’t like him much at all. I came back from school one day, made myself a salami sandwich, sat watching the 10th anniversary of the moon landings on TV and heard a pop from upstairs. Anita came down, covered in blood. Keith by this point was very paranoid so there were guns lying around and this boy found one of them; they were watching The Deer Hunter so I guess he tried to emulate the Russian roulette scene.

“Everyone blamed Anita and that’s when she got the ‘murderess’, ‘witch’ label, but she didn’t kill him and it destroyed her. It was awful, actually.”

After that nadir, Pallenberg began to clean up. She went to live in New York, hung out in the downtown punk scene and spent time with Andy Warhol. She went through detox in 1982, and on returning to London in the 1990s she studied fashion.

What Catching Fire really captures is someone who didn’t seem to care about wealth, fame or beauty despite – or perhaps because of – having all three.

“Her disregard for money, even possessions, was remarkable,” Marlon says. “When I was 13 she burnt all the fur coats Keith gave her, about a million quid’s worth. I was, like, ‘We could sell it!’ She replied, ‘Too many bad memories.’ She always moved forward.

“She said of the Stones, ‘How can they still play Jumpin’ Jack Flash after 40 years?’ ”

Perhaps the best description of Pallenberg comes from the woman herself. “Keith’s a decent guy,” she said. “He’s no angel. But then, neither am I.”

The Times

Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg is released on May 17.