Ancient Rome’s lessons for Israel and Russia

In escalating their wars, the two nations face questions about citizenship, duty and sacrifice.

It was the Roman emperor Augustus who turned the army into a serious career choice. A legionary could expect a hefty pension after 25 years of service, while a soldier from the foreign auxiliary legions had the prospect of Roman citizenship dangled in front of him.

From Scotland to the Red Sea the emperor’s legions were everywhere, guarding walls against barbarian incursion, constructing forts, policing captured lands, setting up training programmes, devising new weapons. They set a benchmark for future armies but also, in their casual cruelties, demonstrated how not to occupy foreign lands.

All modern armies have taken something away from the ancient Roman experience but none more so than Russia and Israel, two sophisticated military powers that have been involved in a succession of increasingly complex wars.

The Russians in particular have been fighting an essentially imperialist war against Ukraine and seem to be borrowing, under their own Caesar, Vladimir Putin, the worst of the Roman war-fighting experience. Putin’s cruel war against the Chechens (his first barbarians), the smashing of Grozny (reminiscent of Tacitus: “they make a desert and call it peace"), the land grab inside Georgia, the annexation of two provinces peopled by Russian speakers, the bombing of Syria, the destruction of Aleppo, the control of the country’s airspace: all this has been a prelude to the two wars (actually a single, decade-long war) against Ukraine. Early in the 2022 phase of war the Russians set an example in the form of a demonstrative atrocity in Bucha, tying the hands of victims, shooting them and dumping them on the kerb as if awaiting the rubbish-recycling lorry.

An unmissable new exhibition at the British Museum dedicated to the Roman legions shows that armies are capable of even worse. “Nobody knew how to do crucifixion better than the Roman army,” says the curator, Richard Abdy. “Rome’s ultimate punishment was everything the state could throw at an individual: a death sentence, torture and – akin to the pillory in early modern society – prolonged humiliation, all rolled into one.” Even Roman soldiers found guilty of cowardice could be crucified. So far the Russian military hasn’t plumbed these depths, although the security services, with their poison cupboards and torture techniques, and the camp guard personnel have their methods.

The Romans, of course, exercised their military predominance in different times; the known world was smaller, the range of weaponry was limited. Indeed the whole concept of escalation was thought about in more modest ways, though still recognisable in today’s wars. The Roman edge was dependent on fast-moving manpower, superior firepower, discipline in the ranks, the capacity, we would say nowadays, to shock and awe.

Even in Augustus’s time that could fall apart. In AD9 a rebel Roman-educated equestrian officer named Arminius drew a Roman force into a narrow strip of land hemmed in between dense woods and swampland. The Germanic tribes he led slaughtered 20,000 Roman soldiers. The result was to limit the edge of the Roman Empire to the Rhine. It took five years for bruised Rome to retaliate.

Although modern Israel was effectively ambushed last October by Hamas barbarians, its military reprisal options have been constrained. It wants to re-establish a sense of deterrence and, to do that, it needs to escalate both against Hamas infrastructure and its Iranian patrons. But since Israel publicly denies being a nuclear power, since Iran denies any intention to build a nuclear bomb and since the US doesn’t want to be drawn into a nuclear exchange with Tehran, Israel has to seek a different route.

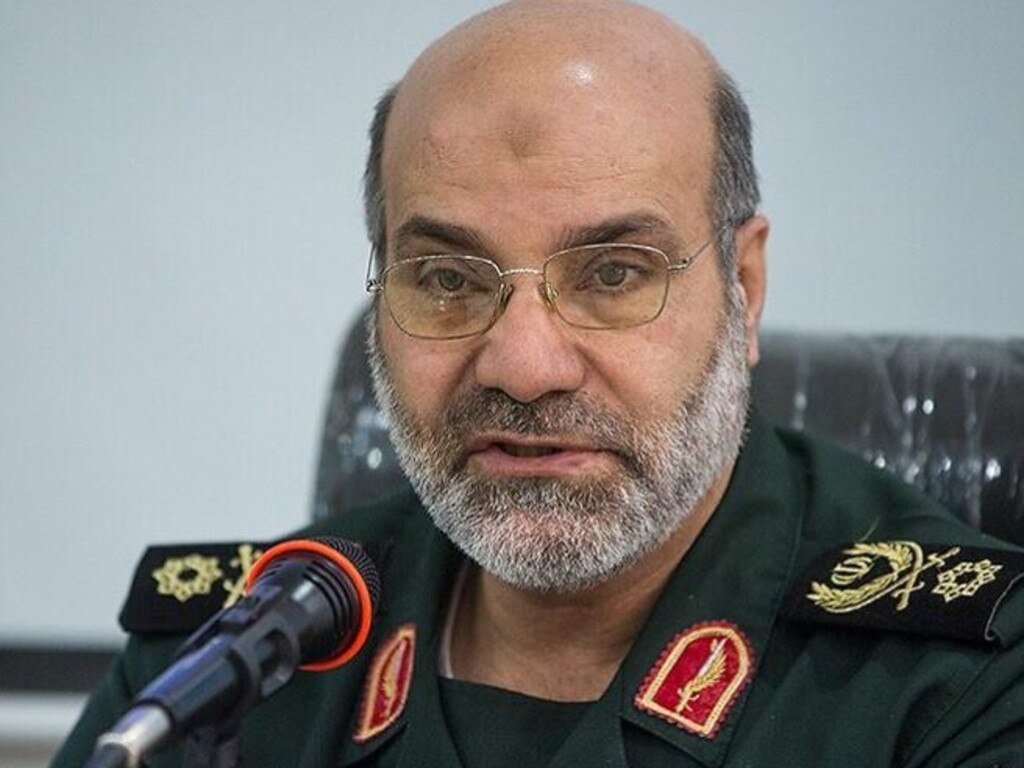

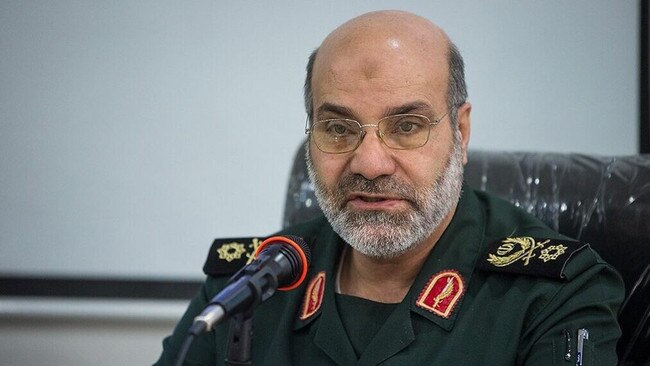

By assassinating this week a top Iranian commander, General Mohammad Reza Zahedi, the Damascus-based liaison between the Revolutionary Guards and Hezbollah, Israel has invited an Iranian counterattack. But the escalation is a calculated one, a ploy to get Iran to drop its mask and demonstrate that Lebanon and Syria are dancing to Tehran’s tune. The point is political: to demonstrate to the US that it is not at war with the Palestinian people but with the Iranian puppet-masters of Hamas.

Non-nuclear escalation depends, much as it did in Roman times, on surges of manpower. Putin has started the ball rolling on a call-up for an additional 150,000 men, in anticipation of a summer offensive. That will be a real test of his support – a better test than the sham election. But it’s the only way left to decisively escalate.

Israel, meanwhile, anticipating a second front opening up to the north of Gaza, needs fresh troops too. An attempt to swell the ranks by calling up previously exempt ultra-orthodox yeshiva students is popular among 18 to 26-year-old non-Haredis who face almost three years’ active service and time in the reserves. It could, however, lead to a walkout from the government of ministers who argue that full-time study of the Torah performs a key service to the nation of Israel.

These are democratic choices unlike those faced by ancient Rome or today’s Putin-land. They demand credible political leadership and an open public discussion within Israel about what, and for whom, Israel is fighting.

The British visitor to the Legion exhibition can count on a useful corrective to his or her classical education. Rome’s armed might was more than Asterix’s slow-witted opponents in Gaul, imperial rule not all bread and circuses. Most of all, though, countries currently at war would find themselves confronted and stimulated by the historical echoes, by questions about citizenship, duty and sacrifice.