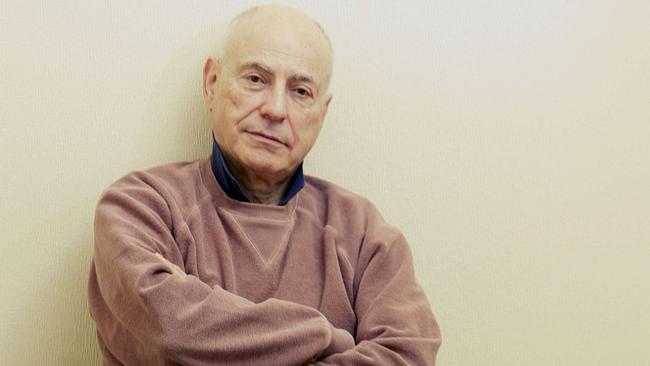

Alan Arkin was master of oddballs and the everyman

Alan Arkin was a prolific actor acclaimed for his portrayal of Yossarian in Catch-22 and the foul-mouthed grandfather in Little Miss Sunshine.

Alan Arkin did not mind that he built a career playing a series of eccentric, manic and curmudgeonly film characters including, famously, Yossarian, the airman who tries to become certified as insane in Catch-22 (1970).

With typical dry wit he liked to claim it was the drug-snorting, sex-mad, foul-mouthed grandpa Edwin Hoover in Little Miss Sunshine (2006) with whom he had most in common – and it was this indie hit that finally won him an Oscar at the age of 72.

The events surrounding the Oscar ceremony seemed almost like an extension of the drama of the film, in which three generations of a dysfunctional family set off on a road trip to a beauty pageant.

First Arkin told the press he hoped his 10-year-old co-star Abigail Breslin would lose because she had enough attention already. “What, next year she is going to get the Nobel prize?” he said, telling journalists he was not joking. Then, when Arkin won the best supporting actor award, Eddie Murphy, who had been the favourite to clinch it, walked out mid-show, ensuring plenty of coverage the next morning.

Arkin was an extremely funny performer who produced a gallery of frustrated and excitable characters, but there was more to both the actor and the man.

He had garnered a couple of Oscar nominations in the 1960s, as the befuddled Soviet submarine commander stranded in Nantucket in Norman Jewison’s Cold War comedy The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming, and for a poignant performance as the deaf and silent newcomer who befriends his landlady’s awkward teenage daughter in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1968), based on the novel by Carson McCullers.

The New York Times described his performance in the latter as “extraordinary, deep and sound. Walking, with his hat jammed flat on his head, among the obese, the mad, the infirm, characters with one leg, broken hip, scarred mouth, failing life, he somehow manages to convey every dimension of his character, especially intelligence.”

He would earn yet another Academy Award nomination (for best supporting actor) for his punchy, profane turn in Ben Affleck’s Argo (2012), in which he played Lester Siegel, the Hollywood veteran recruited to produce a fictional sci-fi film to provide cover for the rescue of American hostages in Iran.

An introspective man, Arkin was somewhat obsessive about life’s great themes of success and failure, and for him acting was a form of therapy for that obsession.

Mike Nichols, who booked him to play Yossarian when he adapted Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 into a film, once rated him the best actor in America and remarked on his ability to “become any person he’s observed, and to make it both real and a comment on the person at the same time”.

Arkin also wrote several children’s books, was a noted photographer, and sang and played guitar with the Tarriers, a folk group who had a top 10 hit on both sides of the Atlantic in the mid-1950s with their version of The Banana Boat Song.

He was born in Brooklyn, New York, into a Jewish family with roots in central and eastern Europe. He grew up in a creative, liberal environment; his mother, Beatrice (nee Wortis), was a schoolteacher; his father, David, was a painter and writer; his uncle was a composer; and Woody Guthrie and Paul Robeson were regular visitors. His father frequently took him to the cinema and from an early age Arkin decided he wanted to be an actor.

“I had the opposite of a stage mother, she wanted me to be an accountant,” he later would reflect. “But she’d sit outside my acting workshops, where I learnt to make faces.”

The family moved to Los Angeles when he was 11. His father worked as a teacher and had hoped to get employment as a set designer but was blacklisted in the McCarthy witch-hunts.

Arkin studied acting at Los Angeles City College and was awarded a scholarship to Bennington College in Vermont but dropped out to play with the Tarriers. After leaving the group, he joined the famous Second City improvisational comedy troupe in Chicago. “I was with Second City for two years but it felt like 30,” he reflected in 2007. “It was incredibly dense and compacted, like a whole lifetime of study. Improvisation is very much a part of my work.” (When he published his memoir in 2011, he gave it the title An Improvised Life.)

He made his Broadway debut in a Second City revue in 1961 and won a Tony award for his performance in the comedy Enter Laughing (1963-64).

Though he had appeared with the Tarriers in Calypso Heat Wave in 1957, it was several years later that Arkin made his auspicious debut as a film actor in The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming; he spent three months studying the Russian language in preparation for the role and duly proved his talent for accents.

In 1966 he directed the little-known Dustin Hoffman as a Cockney nightwatchman in an off-Broadway production of the comedy Eh? It was at Arkin’s invitation that Nichols came to see the play, a visit that would result in Hoffman being cast in his breakthrough role in The Graduate.

On the big screen in the late 1960s, Arkin played a psychotic villain menacing Audrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark, and succeeded Peter Sellers in the third of the Pink Panther films, Inspector Clouseau, but it was not a great success and Sellers subsequently returned to the role.

The 1970s provided some of Arkin’s best and most memorable roles, including the lecherous restaurateur in Last of the Red Hot Lovers (1972); a San Francisco cop causing havoc in Freebie and the Bean (1974); and Sigmund Freud to Nicol Williamson’s Sherlock Holmes and Robert Duvall’s Watson in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976).

Occasionally he also directed films. After a couple of shorts he moved on to features with the satirical Little Murders in 1971. Written by cartoonist Jules Feiffer, the black comedy was set against a backdrop of mounting urban violence and despair. Elliott Gould played a photographer so disillusioned with life that he begins to specialise in pictures of excrement and finds himself subject to new levels of acclaim. The film ends with Gould joining in the mayhem by shooting passers-by.

It made little impression at the time but benefited from critical reappraisal and featured in the 2006 Edinburgh Film Festival’s retrospective of neglected 1970s classics. It owed more to Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel and European nihilism than to Hollywood traditions and it perhaps underlined how little Arkin seemed to care about Hollywood.

His film career dipped in the 1980s but he bounced back in 1992 as one of the desperate real-estate salesmen, alongside Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon and Ed Harris, in David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross, nicknamed “Death of a F..king Salesman” by the actors on account of the swearing.

Through the 1990s he remained in demand for character roles, appearing in Edward Scissorhands, Grosse Pointe Blank, Gattaca and Jakob the Liar, although he distanced himself physically from the film industry, making his home in New Mexico. He amusingly told Time magazine the state had a type of fried doughnut you could not buy anywhere else and many people moved there for them.

More recently he starred in two seasons of the Netflix comedy series The Kominsky Method as the agent to Michael Douglas’s acting coach, which led to Emmy and Golden Globe nominations.

He was married three times, the first to Jeremy Yaffe, with whom he had two sons, Adam and Matthew. His second wife was actor Barbara Dana, with whom he had another son, Anthony. His third wife, Suzanne Newlander, a psychotherapist whom he married in 1996, survives him together with his three sons, all of whom followed their father into acting.

When Adam Arkin was interviewed by Variety about the course of his career, the influence of his father on him was clear: “I often joke about the fact that when other kids were being taken to baseball games and sporting events and fishing trips, my father was taking me to see silent Russian films.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout