No ceasefire will let India and Pakistan escape their history

Even if these nuclear nations are stepping back from the brink in Kashmir, the insurgency at the heart of their dispute will take far longer to resolve.

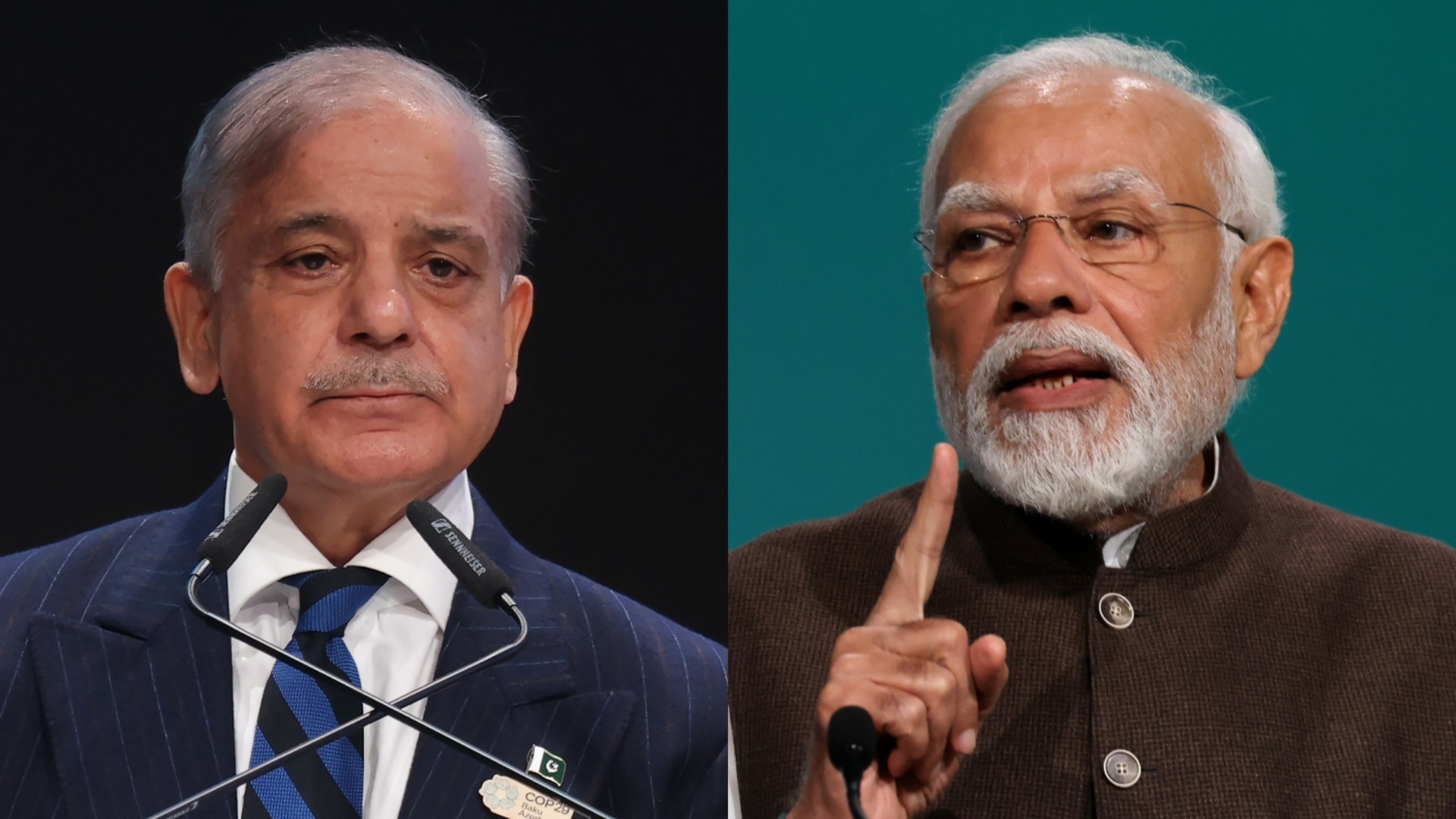

Once again, India and Pakistan have taken each other to the brink of war and – at least for the moment – stepped back.

Explosions and exchanges of fire were reported on Saturday evening across the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir, but the “full and immediate” ceasefire announced by US President Donald Trump earlier in the day appeared to have stopped the escalation of conflict between two nuclear powers.

The success of the American effort to broker a truce probably reflects relief on both sides that someone was offering them a way out, but it is also an indication of the diplomatic clout the United States can still wield when it wants to. By contrast, Russia and China, despite their historic links with India and Pakistan respectively, did little.

The next step will be for the two sides to meet to discuss “a broad set of issues at a neutral site”. This is important. It is vital to get these two neighbours to talk sensibly and productively with each other. As the weaker party, Islamabad has the greater incentive to ease tensions. But abandoning the militants who fight Indian rule in Kashmir would cause divisions at home in Pakistan and it would probably not be believed in India anyway, because the insurgency at the heart of this conflict may continue regardless.

Road to war

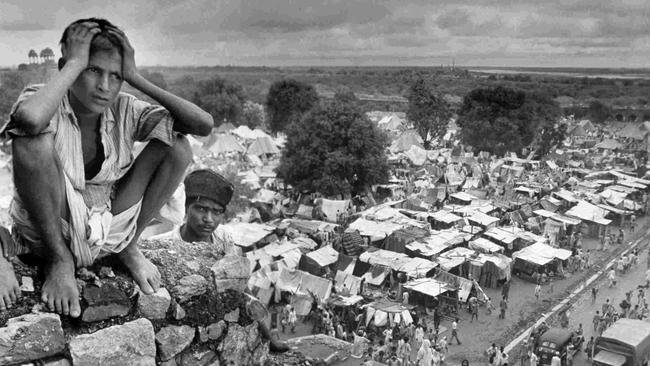

The struggle over Kashmir began as soon as India and Pakistan came into existence with the partition of the old British Raj in 1947. The Hindu Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir decided to join India, despite having a majority Muslim population. This led to a war. When a ceasefire came into force at the start of 1949, India controlled twice as much of this territory as Pakistan. The ceasefire line, known after 1972 as the Line of Control, remains in place.

The original dispute was never resolved and has led to regular military clashes. One in 1965 was substantial, when India accused Pakistan of promoting an insurgency in Kashmir and invaded, leading to a war that involved big tank battles and substantial casualties.

India cemented its position as the stronger of the two powers in December 1971, this time in a war not about Kashmir but over a rebellion in the eastern part of Pakistan against rule from its west. By forcing the Pakistani garrison in the east to surrender, India helped to create the state of Bangladesh. After this came a major effort to build ties.

In the late 1980s relations deteriorated because of unrest inside Kashmir against Indian rule. The developing insurgency was backed by Pakistan. There were regular confrontations with Indian troops plus bombings and abductions.

In early 1999 the conflict moved to a new level when Pakistani soldiers infiltrated Kashmir and seized positions in the Kargil district. It took two months of fighting for most of the infiltrators to be pushed out. Pakistan was put under pressure from the US and others to remove its remaining forces from Indian territory. As they had been struggling in the fighting and had suffered high casualties, the defeated Pakistanis withdrew and the ceasefire was restored.

One reason for the intense international effort to bring the Kargil War to a quick conclusion was that both countries had tested nuclear weapons in the previous year.

From this point on, every clash between the two countries has appeared to carry a risk of escalation to nuclear exchanges. (They now have about 170 warheads each.)

The terror era

International fear of nuclear war has not stopped the violence. In the 21st century it has often involved Islamist terror groups, allegedly backed by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Not all of the attacks have been in Kashmir. Not long after the attacks of 9/11 on the United States by al-Qaeda, which had its own ISI links, there was a terrorist attack on the Legislative Assembly in Kashmir on 1 October, 2001, and then another on the Indian parliament in Delhi on December 13, 2001.

One of the most horrific came in November 2008, when members of the Pakistani-based Islamist group Lashkar-e-Taiba laid siege to Mumbai for 10 days, attacking a range of sites including hotels and a synagogue, resulting in 166 deaths along with nine of the terrorists. In both of these cases a concerted international effort was required to prevent war between the two countries. India alleges that Pakistan is still shielding some of those involved in planning and carrying out the Mumbai attack.

In two crises since – in 2016 and 2019 – a pattern was established. In both cases Jaish-e-Mohammad, another group with alleged ties to ISI, attacked Indian military units inside Kashmir. India responded by attacking Pakistani targets. After a flurry of military activity both sides claimed victory and the situation calmed down.

But the underlying political tension remained.

After the 2019 crisis Narendra Modi’s government took a firmer grip on the Indian-controlled part of Kashmir by imposing direct rule, suppressing the media and making many arrests.

The current crisis began on April 22, when a group formed in response to the crackdown, associated with Lashkar-e-Taiba, attacked tourists visiting Pahalgam in Kashmir, killing 26 and wounding another 10.

This led last Wednesday night to Indian strikes against targets inside Pakistani-controlled Kashmir but also in the Pakistani Punjab.

Pakistan claimed to have shot down five Indian aircraft. Islamabad seemed to have judged this to be a sufficient response, but the conflict failed to wind down. Instead there was deadly cross-border artillery fire, drone strikes, and then reported missile attacks on air bases and troop movements close to the border.

With official information tightly controlled, the two countries have been awash with rumour and counter-rumour. As with the previous bouts, claims are made about the damage done to the enemy, some plausible but many absurd. In the past these exaggerations had the benefit of satisfying domestic audiences that enough has been done, providing cover should either government wish to back down. This may be at work again, enabling both sides to agree to a ceasefire.

This crisis was different

While there are similarities between the past three weeks and previous bouts of fighting, some features were different and made it more dangerous, starting with initial attacks being directed against civilians rather than military personnel and an Indian response that went deep into Pakistan.

Pakistan wanted to show that it could match India blow for blow, but was also aware that in a full-blown war India would have the advantage.

It has the larger military, spending nine times more than Pakistan on its defence, and some 1.5 million personnel in its armed forces, twice as many as Pakistan, with superiority in tanks and artillery. India’s navy is large and Pakistan’s small. India has the numerical advantage in aircraft. Both have some fourth-generation multi-role aircraft.

What will be of concern to India, and western countries looking on, is that India’s French-built Rafales, as well as a couple of Russian-built jets, were shot down by Pakistan’s Chinese-built J-10s using air-to-air missiles. We need to know more, including about Indian tactics, before large conclusions are drawn about this. It is notable, however, that India quickly moved to long-range drones for its later attacks, this time against Lahore and Karachi. Some of these were shot down (as were Pakistani drones by India), but there was also some success on strikes against Pakistan’s air defences.

Because India enjoys conventional superiority, Pakistan has warned in the past that if it was invaded it could resort to nuclear use. It tested short-range ballistic missiles after the terrorist attack in Kashmir and just before the Indian strikes to underline its capabilities. As with previous crises there were concerns that if the fighting became more serious India would be tempted to try to take out Pakistan’s weapons in a pre-emptive strike. The language used by both sides indicated that they wanted to keep the fighting contained.

Nonetheless, when two nuclear powers fight each other it is hard not to be anxious. The intensity of this conflict was far from the nuclear threshold but there is always a risk of miscalculation.

The American factor

Relations between the two countries are at rock bottom. Visa-free travel and bilateral trade are suspended, airspace is closed to each other’s aircraft and diplomatic staffing has fallen from already low levels.

One factor that may have encouraged the decision-makers in Islamabad to accept an early conclusion is that while India is a fast-growing economy, projected to become the fourth largest in the world this year, Pakistan is much weaker. The country is struggling with debt and trying to extend a $US7 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund, which India appears to be trying to block. Early in the crisis, India suspended the Indus Waters Treaty, stirring fear for Pakistan’s irrigation system.

Some Middle Eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia, explored mediation but without success. Having done little beyond express concern and regret in the early days of the crisis, America began to involve itself: Marco Rubio, the secretary of state, urged de-escalation in separate calls to leaders from both countries. JD Vance, the vice president, had recently visited India and also seems to have been involved in the ceasefire discussions.

The US has historically been close to Pakistan because of their co-operation in the Cold War and later in the “war on terror”, even though Washington grew to fear that Pakistan was playing a double game by backing Islamist groups.

Since withdrawing from Afghanistan in 2021 the US has shown less interest and instead sought to improve relations with India. For its part India has long had close relations with Russia and been wary of China. This has become more complicated recently as Moscow has sought to forge a closer partnership with Beijing.

Warfare of the sort that threatened to unfold last week can be difficult to conclude. The challenge for the next stage of negotiations is that senior Pakistani military figures will still be reluctant to hold back militants in Kashmir while the Indian government will continue to demand that Pakistan end support for terrorist groups.

Ceasefire or not, there’s still no obvious resolution to a conflict that has defined Indo-Pakistani relations since 1947.

Sir Lawrence Freedman is emeritus professor of war studies at King’s College London and co-author of the Substack newsletter Comment is Freed.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout