September 11: We waited for the injured, but they never arrived

Of all the loud and brutal things that happened in front of me on 9/11, a few words are among the ones I hear the clearest 20 years later.

Of all the loud and brutal things that happened in front of me that day, a few words are among the ones I hear the clearest 20 years later.

“You’re all in the red zone,” the man in charge said, waving his hand at us with a sense of urgency driven by what we expected next.

Red. That’s where people will be dying. I’m not sure I can do that. I’m better suited to the green zone, I thought.

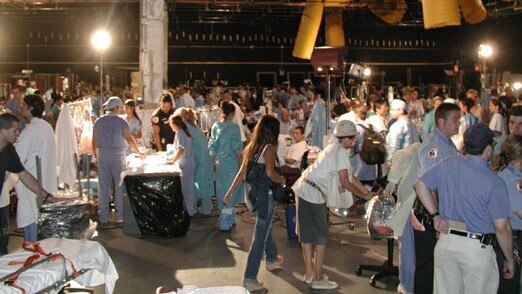

The enormous indoor space was divided into four colours: green for the walking wounded, yellow for seriously injured, red for the critically injured and black for the bodies.

But red it was. I walked towards the trestle table, one of hundreds being set up as Chelsea Piers, on New York City’s Hudson River, transformed into an emergency field hospital. Five hundred injured were on their way, we were told.

At 8.46am, on September 11, 2001, American Airlines FL11 hit the north tower of the World Trade Centre, knocking the world off its axis. A murderous era of international terrorism was born in an instant, bringing attacks to cities across the globe, including in Australia.

Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq started at that moment. In time, entire Middle Eastern nations would be engulfed in revolution. Almost 3000 people died on 9/11. Tens of thousands more would die in the conflicts that followed.

That day changed the way we travelled. It changed the way we lived at home. But for all of September 11’s epic global significance, it was also a particularly intimate event. People remember where they were when they heard the news.

On Monday morning, Melbourne radio station 3AW’s Ross and Russel asked listeners to share their 9/11 stories. The switchboard crackled as people recalled watching the planes hit the towers and fall on TV. One man recalled how he pulled his car over, ran to the car in front, banged on the roof, and said you have to listen to this.

Another remembered racing in to wake his wife, before the couple sat up in bed watching real reality TV. A man talked about how his daughter’s birthday falls on September 11, and he’s lived with the happy and sad of that day ever since.

That Tuesday night, across Australia, people got out of bed or didn’t go to bed.

On the eve of Saturday’s 20th anniversary, the emotion was evident in every call. Everyone, it seems, has their September 11. Each of them as emotional as the next.

Listening to Ross and Russel last Monday, my mind turned back: Our September 11 started in 6G, 228 West 71st, on the Upper West Side. Kim Wilson and I were married the previous November and flew to New York, arriving in the midst of a belting snowstorm on January 2.

We checked in to the DoubleTree Hotel on Times Square and, like pretty much every other journo couple in New York, went to Langan’s Irish pub for a beer.

Over the coming months we learned to live with the snow and the stinging wind racing down those grand skyscraper lined wind tunnels. We were in New York City. Life was freezing but it was so amazing.

By May, the weather finally turned the corner and Central Park blossomed into a green and warm wonderland. Picnics, jogging around the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir, hot August nights with a Thermos full of margarita and a roast chook sitting in the Sheep’s Meadow was life. Regular nights out down the funkier end of town around SoHo were great, but the Upper West Side was our hood in the summer of 2001.

September 11 changed that. The city was traumatised. Everywhere, photos of missing loved ones were stuck up by desperate relatives. Like many others, we developed an emergency plan in the event of another attack. We filled backpacks with cash, food and water and nominated a location to meet if something happened and we couldn’t speak. Fighter planes circled overhead.

That morning was amazing in New York. It was warm. The sky was blue. It was a bloody great day to be in this great city.

As my wife left our apartment, CNN started showing footage of smoke billowing from the north tower. Must be one of those tourism charter flights, I said. Seems like a lot of smoke, though.

“You’re going to have a busy day,” Kim said, shutting the door, and heading to the subway to her Chelsea office.

Then the second plane went in. That was no charter flight.

The yellow cab speeds alongside the Hudson. When it reaches the point where the island doglegs, the towers come into view; two giant smoke stacks. I looked at the driver, “F--k”.

We hit traffic and the cab ride was over. I started walking. I reached West Broadway, turned south, crossing Lispenard, Walker, White, Franklin and Leonard streets. I’m on the mobile dictating copy back to the Herald Sun newsroom. For the final part of the cab ride, I had lost sight of the towers. But on West Broadway, the view south opened up. There was only one tower now.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve written and thought about September 11, in particular the view I saw at that moment. The day never grows less violent. The tragedy of Afghanistan in recent weeks, coinciding with the 9/11 anniversary, has reinforced the waste of human life that Tuesday so long ago.

I’ve retraced my steps down West Broadway in 2009, 2016 and 2019. I’m not sure why I keep doing that. A new tower might have risen, but my view hasn’t changed. I think it’s an attempt to touch the past. Maybe to confirm in my mind that I didn’t watch it on TV, and that I was standing five blocks from the north tower when it fell.

In 2016, while walking through the 9/11 memorial, I was stunned to see the Herald Sun’s front page – headlined America Attacked – carrying the bylines of me and my mate Michael Beach. There it was. Proof my mind wasn’t playing tricks. Still, in 2019, I trod the same steps down West Broadway just to make sure.

Even now, as a father of three a lifetime away in Victoria, my breathing gets shallow and my pulse quickens writing about the intersection of West Broadway and Chambers Street. As I looked up 110 storeys, chunks of the north tower were breaking off. There was so much smoke pouring skyward. About 15 storeys down, flames were glowing.

At ground level, fire engine and police sirens screamed, people ran every which way, others were glued to the road looking at the horror show. Some were hysterical. Noise was coming from everywhere.

Warren St was the next street I was walking to. Then Murray, Park, Barclay and Vesey streets stood between me and the tower.

As I reached the middle of the intersection of West Broadway and Chambers St, the top 15 or so floors dislocated and just for a second seemed to shudder. Then it collapsed on itself. I’ve rewatched this moment on YouTube to work out how long I was standing there watching. It takes about 10 seconds to fall. Count to 10, that’s a long time. It was like a growl coming up from underneath, yet it was falling from above.

As I was standing and watching, the fallen tower turned into an ash cloud that barrelled towards me. I tried to outrun it. Tried to hide under a car, before abandoning that idea. I was consumed. The brilliant blue sky turned grey, then brown, then black. It was choking. My eyes stung in their contact lenses. There was a taste of scorched metal and the smell of burned plastic.

I bang on the door of a Greek restaurant. A woman inside fumbles with the deadlock, then gives up. I’m having trouble breathing. I am trapped outside. She signals to a side door. I crawl towards it. At the side door, the woman again cannot unlock the door. I kick the glass door. The glass shatters but does not break. “Open the f---ing door.”

A man appears beside the woman with fresh instructions – go back to the original door. I crawl back. He opens it and I fall inside. Being engulfed in smoke seemed to last forever. It was probably no more than 20 seconds.

Stepping outside, the streets were a dusty moonscape and office documents – I picked them up and saw they were legal and accounting papers – rained.

Cars a few blocks on have burst into flames.

Minutes earlier, Kim had arrived at her office at 23rd and 9th Ave in Chelsea.

“When I got into the small elevator to go to the 7th floor a couple of people followed me in. One of them was talking to another saying two planes had gone into the World Trade Centre. I thought to myself, ‘Bloody Americans, they always exaggerate everything’,” she recalled.

As the towers came down, Kim was standing on the roof of her 12-storey office; “We could see the smoking towers off in the distance, as mid-town was slightly elevated above downtown.

“It only felt like a few minutes before we saw a huge plume of smoke rise and then what seemed to be only a single tower standing. Surely not. I rubbed my eyes, thinking they must be gritty and clouded by dust and smoke. But what my eyes were telling me was fact, the first tower had collapsed.

“I felt the air rapidly leave my lungs. The shock of it literally took my breath away. We continued to watch, not seriously contemplating that we would see the second tower crumble before our eyes. But it did.

“Everyone in the office decided to head home. A handful of us were headed uptown, the others downtown. We hugged and started walking. There were literally thousands of people walking, bewildered and overwhelmed up the centre of one of the major arterials of Manhattan. Colleagues peeled off as we made our way home until it was just me walking among thousands of strangers. We felt strangely connected. There was more eye contact and gentle smiles than I’d seen in my entire time in New York.

“I poked my head into a bar with the TV on to get an update. Fighter jets were buzzing overhead and I was scared. News was emerging of plane crashes in Washington and Pennsylvania.”

Back at what would soon be known as Ground Zero, an emergency medical station set up on the street was treating a few lightly injured. A doctor called for volunteers to man a bigger pop-up hospital. I jumped in his car. But instead of heading south, it headed north to Chelsea Piers.

Waiting at my assigned red zone table is a doctor from Ohio, in New York for a conference. Surgical gowns, bandages and instruments are being distributed.

I’ve written about what the doctor told me a few times and I still find the conversation confronting: get prepared for plenty of “combat-style” injuries and “blunt trauma”.

“Do you know how to fit a drip?” “No.”

What do you know about medicine?” “Nothing”.

“Do not touch a patient unless I say so.” “OK.”

“This is important. Your face will give away a patient’s condition to them. Whatever you see, no matter how bad a patient is, it’s important when you look them in the eye your face doesn’t give this away.” “OK.”

“I’ve worked for more than a decade as a surgeon, but I’ve never done combat surgery, and this is what I reckon it’ll be like. I just don’t know whether we have the stuff we need to do much, but we’ll have to make do. We’re gonna get lots of blunt trauma.”

Ambulances drop some lightly injured firefighters off, but in the red zone there is nothing to do but wait. We waited for hours. The expected arrival of hundreds of injured never happened. By 7pm, there was nothing. They’re all dead.

I walked out of Chelsea Piers. Bought a six pack of Miller from a cantina and headed uptown through a deserted Manhattan to my office at 1211 Ave of the Americas. Drinking my beer, I passed no one. I stood in Times Square, under the neon, and thought, what happens next?

Life is what happens. Twenty years on, we have proof.

September 11, a day defined by hate, focused our minds on what was important, and that was love and life. Much earlier than we had planned, we started our family.

Harry was born in New York on November 29, 2002. A living, joyous and growing reminder of this remarkable city and hope.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout