The prince, his money manager and the corruption scandal rocking Monaco

Prince Albert safeguarded the family’s fortune and their secrets. Now, it’s all unravelling. Claude Palmero was the financial gatekeeper. The relationship turned sour in 2023.

Tucked one street behind Monte Carlo’s historic harbour, which is famously dotted with champagne bars and anchored by the storied casino that was the backdrop to multiple James Bond films, the Monaco police station may be the most unglamorous building in one of the world’s most glamorous settings.

Gray and boxy, it looks more like student housing on a university campus than a bulwark of security for the global elite who flock here as much for its aura of protective secrecy as its shimmering scenery.

But over two days this February, in the police captain’s office with a window facing up the rocky slope toward the palace, a dapper 68-year-old suspect in a corruption scandal rattled one of Europe’s most storied royal families and shook the foundations of a tiny country built on polished appearances, ironclad confidentiality and tightly choreographed power.

The suspect, Claude Palmero, has salt-and-pepper hair and wears wire-rim glasses. If he looks like an accountant, it’s because he is, and he now finds himself at the centre of the alleged corruption scandal.

For much of his adult life, Palmero was the financial gatekeeper for Prince Albert II, Monaco’s ruler for the past two decades and the son of Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace, the Oscar-winning actress formerly known as Grace Kelly.

A devoted sportsman, environmentalist and philanthropist, 67-year-old Albert has a fortune that has been conservatively estimated at more than €1 billion ($1.75bn), and by all accounts he historically paid little attention to how it was managed. Instead, he entrusted it to Palmero as his administrateur des biens.

That role, which Palmero inherited from his father, empowered him to manage Albert’s private fortune, including by orchestrating quiet cash transfers when requested by the prince or others in the royal family.

Palmero oversaw not only Prince Albert’s private fortune but also assets held by the Crown, from prime real estate to a vast array of collections – including cars, stamps, coins and artworks, as well as financial holdings.

But the relationship turned sour in 2023, after a leak of hacked documents implicated Palmero in a number of alleged corruption and influence-peddling schemes.

In a casual text message that belied the chaos that was to come, Albert in May of 2023 wrote to his longtime money manager: “I am now more or less obliged to speak out … to ‘blow the whistle’ a little bit to signal the end of recess and try to reassure many people here at home.” He fired Palmero weeks later.

Albert also initiated a broader shake-up at the top of the principality. Dozens of insiders left their posts, including some of Monaco’s most influential powerbrokers.

The move kicked off a wave of recriminations and more damaging leaks, including from notebooks Palmero meticulously kept about the prince’s private activities.

French newspapers ran some contents of the notebooks, highlighting Albert’s financial support for his children born out of wedlock and their mothers, as well as the spending of his wife – Princess Charlene, a former Olympic swimmer – and other members of the royal family.

(Monaco is a principality, not a kingdom, though the public widely refers to its ruling dynasty as a royal family.)

In September 2023, Albert ratcheted up the feud further by filing a lawsuit – along with his sisters – against Palmero, accusing him of breach of trust and theft. The charges were later expanded to include forgery, use of forged documents and money laundering. According to people close to the prince, it was the first time in over 700 years of the Grimaldi dynasty that a ruler filed a criminal complaint against a Monaco resident.

The February interrogations at the police station, spanning two full days, were part of the continuing investigation that is discreetly winding its way through Monaco’s courts.

Palmero has been questioned about Panamanian holding companies, Swiss bank accounts and secret payments made to keep the prince’s private life exactly that – private. During questioning, he was not even allowed to use the bathroom without a guard escort.

Palmero has denied the allegations. Prosecutors have interviewed him on multiple occasions but have not brought any charges. Palmero’s defence can be boiled down to this: All of his activity was designed with the best interests of the prince in mind, including cleaning up the messes made by Albert and other members of the royal family, who paid little attention to their finances and spending.

In February, for example, Palmero was asked about a roughly $US15.9m ($24.6m) transfer he made to a company called Étoile de Mer.

Palmero referred the officer to a letter addressed to the prince’s legal team, explaining that the funds had ultimately ended up with a company used to cover expenses tied to Nicole Coste, the former Air France flight attendant and one-time lover of Prince Albert, as well as their son, Alexandre.

The prince “wished for the utmost confidentiality so that this situation would not become known to his wife’’, the letter read, according to documents viewed by WSJ. Magazine.

Police investigators also questioned Palmero about a $US795,000 transfer flagged by auditors as “suspect’’. He described it as reimbursement for years of unlogged spending on behalf of the prince himself, kept private “for reasons of confidentiality” and his own sense of duty and discretion.

Among the outlays Palmero claimed to have quietly absorbed: rent for the prince’s Monaco bachelor pad, the salaries and housing arrangements for Coste’s staff and assorted costs tied to Princess Charlene’s private Monaco apartment, which he said were deliberately kept off the books to avoid leaving evidence that she sometimes stayed outside the palace.

The commingling of funds was further complicated by Palmero’s practice of investing alongside the royal family, which he said he could do because he has a personal fortune of more than $US113.5m, much of which came from an inheritance.

In one instance, police pressed Palmero on why some $US185m – mostly in private-equity funds – was held in a company called Janus, which was owned by Palmero.

“Janus is a two-headed god,” Palmero told police, implying that this was no coincidence. “There were two people involved.”

At times, Palmero got exasperated by the questioning, saying of his former boss: “He now pretends that for 22 years he knew nothing about the state or management conditions of his own assets? He is the sovereign of a state! So either he is lying to serve his own interests, or he should step down – because someone like that should not be allowed to manage anything! It’s utterly ridiculous!”

Some of the prince’s allies agree with at least part of that assessment, suggesting the prince placed too much trust in familiar faces. Surrounded by old friends and advisers who echoed each other’s views, he saw little cause for doubt. The scandal, they say, jolted him into seeing things differently.

Prince Albert took the throne 20 years ago this July, promising to usher in a new era in which Monaco would stand for something more than immense wealth for its own sake. But the scandal is merely reinforcing to many outsiders the famous Monaco descriptor from Somerset Maugham: “A sunny place for shady people’’.

In a statement to WSJ. Magazine, Jean-Michel Darrois, Prince Albert’s lawyer, said the prince would not comment on the specifics of the scandal and the dispute with Palmero.

“Of course, this episode has been difficult,” Darrois said. “He has taken all necessary decisions and measures to address the issues, strengthen governance and ensure full transparency. The matter is now in the hands of the judiciary, in which he has complete confidence. His focus is now fully on Monaco’s future.”

Palmero’s lawyers dismissed the allegations, saying that his management of the family’s assets had only ever been profitable. “The false indignation of the princely family – especially Prince Albert’s – inventing that their estate administrator of 22 years might have tried to appropriate their assets, is utterly staggering,” they said. The lawyers described the barrage of lawsuits as a “palace vendetta” aimed at silencing Palmero’s fight against corruption.

With no income tax for individuals and an obsession with privacy, Monaco is a magnet for billionaires, celebrities and high-net-worth expats looking to shelter fortunes in plain sight. Property prices regularly hit over $US110,000 per square metre, making it some of the most expensive real estate on earth. The harbour in the sun-dappled Mediterranean hosts a parade of superyachts – floating mansions stacked with helipads and champagne decks, all moored just steps from the palace.

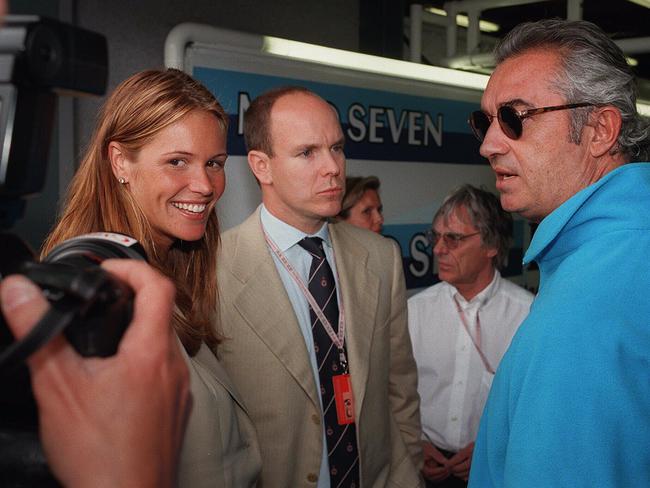

And once a year, the entire city transforms into a high-octane playground for the Monaco Grand Prix, when Formula 1 cars scream through the narrow streets, watched from private terraces and luxury suites perched above the track.

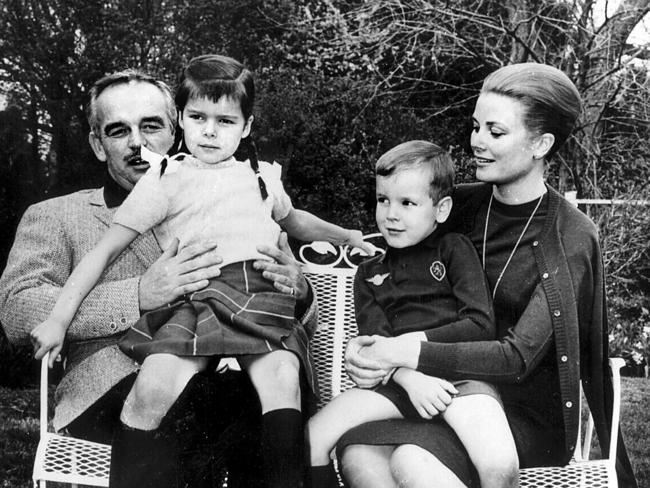

The principality’s global status is largely the creation of Albert’s father, Prince Rainier III, who ruled for over 50 years. In 1956, he married Grace Kelly, the Hollywood starlet whose image helped cement Monaco’s mystique on the world stage until her death in a car accident in 1982.

As their only son, Albert grew up under intense public scrutiny, groomed for leadership – but made to wait.

Despite years of speculation, Rainier held on to power far longer than expected. Insiders were convinced he’d step down in 1997 as part of the 700th anniversary of the Grimaldi dynasty. Then again in 1998, when he turned 75. Some were certain he’d pass the baton on the 50th anniversary of his reign in 1999. Each time, it didn’t happen.

Albert finally ascended the throne in 2005, at age 47, only after Rainier’s death.

Albert himself has always cut a different figure from the classic monarch. He’s a committed sportsman – an avid tennis player and a black belt in judo. He has competed in five Winter Olympics as part of Monaco’s bobsled team. He’s also known for a colourful personal life, marked by a long history of romantic entanglements.

A graduate of Amherst College in Massachusetts, he was asked in 2021 by the student newspaper to name his favourite course. “Wow, maybe human sexuality? No, no, no, [laughs] I don’t know,” he said. He went on to say political science and the arts were subjects that captured his interest.

In the same interview, he noted that he held a job at Amherst, working briefly as an art library attendant. “It was great to know what it feels like to earn a pay cheque,” he said. “Not that I don’t get paid in Monaco, but I don’t really see my pay cheque.”

That casual attitude toward money in many ways paved the way to today’s scandal.

In 2023, on another visit back to campus, Albert decided that he wanted to donate millions to fund a new residential building at Amherst – maybe name it after himself or Monaco. Palmero informed him that his investments weren’t liquid enough to allow him to make the donation immediately, as the prince wanted, and that it would take weeks to assemble that much cash.

Palmero said some in the prince’s inner circle used the episode to try to convince him that his money manager was stealing from him.

“Either he believed that or he pretended to believe it,” Palmero told WSJ. Magazine.

Fuelling Albert’s suspicions was the lingering fallout from the Dossiers du Rocher leak two years earlier. Hackers had breached the inbox of Thierry Lacoste – one of Albert’s lawyers and an old family friend – unearthing documents that were later presented as evidence of alleged corruption inside the palace and implicating top advisers, including Palmero.

The prince had initially brushed it off, backing his inner circle. But when the French investigative program Complément d’Enquête aired a damning exposé about the leak, his patience snapped.

Shortly after, the prince confronted his longtime moneyman and asked him to step aside. Palmero refused, and Albert then terminated him. Palmero, for his part, dismissed the corruption allegations as a calculated smear campaign tied to rivalries in Monaco’s high-stakes real estate sector.

Palmero was given one hour to vacate the office he had occupied for 22 years. On that day in 2023, he left the office with eight boxes and bags full of documents, according to police testimony from Salim Zeghdar, Palmero’s successor. Afterward, the Carabinieri sealed the office.

The prince and his associates scrambled to piece together his fortune. The day after Palmero’s departure, they brought in specialists to break into Palmero’s safe, hoping to find key documents outlining his financial affairs. But the safe contained only a handful of old documents dating back to the 1980s – nothing of substance, and certainly nothing that could help reconstitute the sprawling fortune of the Crown, according to people close to the prince.

That discovery sparked panic inside the palace walls: how would they claw back the fortune and bring it under the Crown’s name? And what if Palmero were to suddenly die? With so many critical documents seemingly still in his possession, the prince feared that massive pieces of the royal treasure could disappear forever – or end up trapped in legal limbo.

“Basically, I had no idea what assets I was supposed to manage,” Zeghdar told police. “Above all, I couldn’t understand the relationships between the companies – at first glance, it looked like a multilayered structure designed to create total opacity.”

Palmero, for his part, denies all this. He claims the safe was opened illegally, behind his back, and says the official inventory is fiction. As for why he didn’t assist in the transition, he says he had been placed on medical leave for depression, brought on by the pressure and what he describes as a campaign against him.

Prince Albert ordered an internal investigation into where and how his assets had been invested — and brought in corporate auditors from Alvarez & Marsal to tear through the books.

What they uncovered, according to people close to the prince, was downright alarming.

In several cases, Palmero appeared to have set up co-investment arrangements where he quietly took a stake alongside the prince and his family. According to people familiar with the internal investigation, Palmero would put in an amount of money, wait to see how the investment performed – and if it paid off, increase his stake a year later. If it didn’t? He’d reduce or drop it altogether.

Palmero denied changing the stakes after the fact and described the overall setup as a classic case of “alignment of interests” – a financial principle where the manager invests his own money alongside the client’s.

“It’s a necessity,” he said. “The manager and the principal win and lose at the same time.”

Yet Zeghdar later told police that neither the agency – nor the prince himself – had any idea this was how things were being run.

Even more startling, according to members of the prince’s own inner circle, was the auditors’ finding that Palmero had allegedly used palace funds to buy items far outside his mandate – including surveillance gear. Among the purchases: a secure server worth over $US260,000 and three military-grade Black Hornet drones totalling $US127,943.

In his police testimony, Zeghdar said the drones “must have been used to spy on people connected to the Dossiers du Rocher,” referring to the hack of Thierry Lacoste’s inbox – an allegation Palmero denied in his own interview with police. Palmero and a security consultant he worked closely with each told police that the prince was aware of all their activities.

As investigators kept turning up what they saw as shady payments and financial loose ends, Prince Albert began weighing a dramatic step: filing criminal charges.

His lawyers and PR team huddled over the pros and cons. This wasn’t just a legal battle – launching a complaint against Palmero could blow the lid off some of the palace’s most closely guarded secrets.

Palmero knew a lot, including how much Albert had quietly paid to support children from past affairs and details of the hush-hush apartment he kept in Monaco.

His communications adviser walked the prince through the worst-case scenario – tabloid frenzy and damage to his reputation.

Still, Albert pressed ahead. On September 18, 2023, the prince and his sisters filed a complaint against Palmero that put the number of companies owned by members of the princely family in which Palmero held shares – directly or indirectly – at 47.

Several months later, the warnings that the palace dirt could be leaked were realised.

After Palmero’s dismissal from the palace, police had searched his residences and seized the notebooks, which contained detailed accounts of the royal household’s financial inner workings. They were returned to him in August, when Palmero picked them up in person from the station, and in January of 2024 Le Monde published a series of stories about their contents.

At the centre of some of the most eye-popping disclosures is Prince Albert’s wife, Princess Charlene. Palmero’s records describe unchecked spending, under-the-table staffing and what Palmero called a complete lack of oversight. Her office was redecorated at a cost of $US1.1m. Over eight years, Palmero wrote that she spent $US17m – despite receiving just $US8.5m in official allowances.

“I have no control over the princess’s expenses,” Palmero wrote in December 2018.

She also employed off-the-books staff, including Filipino workers, one of whom had overstayed a tourist visa by five years. He noted in 2021 that Charlene had 8.5 personal staff – more than any other royal. Her brother, Sean Wittstock, received just over $US1m in payments toward a house, despite having no official role in the palace.

Albert’s private affairs were also quietly – but carefully – financed, according to the contents of the notebooks reviewed by WSJ. Magazine. His daughter Jazmin Grace Grimaldi was given an apartment in New York and received a quarterly allowance of $US88,600. His son Alexandre, born to the former flight attendant Nicole Coste, received support through a shell company structure designed to keep the arrangement discreet.

At one point, an alarmed Palmero warned the prince that his spending on Coste’s fashion venture was “trending towards [$US1.1] million a year”, according to the notebooks.

The revelations were embarrassing and invasive, but little by little, the prince began piecing his fortune back together – including the fact that much of it was held at Reyl bank in Geneva.

On June 28, 2023, Prince Albert and a team of advisers and lawyers travelled to the bank’s offices. In the early afternoon, a lawyer representing Palmero handed over the keys to the safe at the bank.

What they found proved crucial for Prince Albert’s team: The papers helped identify a number of Panamanian holding companies, dating back to the 1980s, that belonged to the prince and his two sisters.

It would take months, according to people close to the palace, to work out what all the companies owned. Still, after the visit to Switzerland, a large part of the royal family’s fortune was now accounted for – and confirmed to be in Albert’s hands.

After numerous terse exchanges between lawyers on both sides, the palace was in control of nearly all of its wealth. It also agreed to transfer to Palmero a portion of the investment vehicle shares to which he said he was entitled – amounting to $US3.2m – and he also received a settlement related to the personal expenses he said he covered on behalf of the prince.

But the financial disentanglement is not complete. Negotiations between the two sides are continuing.

Even as Prince Albert has worked to reassert control over his financial affairs at home, he has carried on with the quiet choreography of state.

Earlier in the spring, Prince Albert toured France to spotlight the Grimaldi family’s historic ties to various northern regions.

Albert and Princess Charlene also joined mourners at the Vatican for Pope Francis’s funeral in St. Peter’s Square.

On July 19, all Monegasque citizens are invited to join Prince Albert and Princess Charlene for a cocktail party on the palace square to mark his 20 years on the throne.

For his part, Palmero insists he will fight for as long as it takes to restore his honour, and has now taken his case to the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that he is a victim and cannot receive a fair trial in Monaco. He points out that Prince Albert is also officially the head of the judiciary.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout