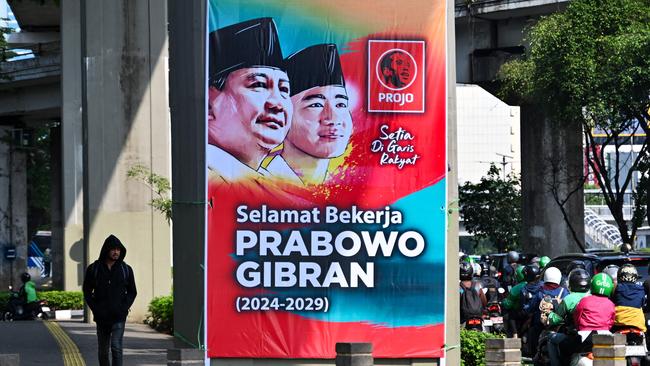

Indonesia’s Prabowo signals ‘realist’ foreign policy ahead of swearing-in

The retreat include the founder of the world’s biggest hedge fund and US foreign policy academic Jonathon Mearsheimer.

For a peek into Indonesia’s foreign policy direction under incoming president Prabowo Subianto, one could do worse than scan the list of international speakers who featured at a retreat this week for dozens of new cabinet ministers at his sprawling ranch outside Jakarta.

Just days ahead of Prabowo’s Sunday swearing-in ceremony, the former special forces commander flew in his favourite political scientist Jonathon Mearsheimer, a US academic whose “offensive realism” theory argues the anarchic nature of the international system promotes the sort of aggressive state behaviour now seen in the escalating US-China rivalry, to give a lecture on geopolitics.

Mearsheimer opposes Israel’s war in Gaza as a strategic blunder, blames NATO’s expansion for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and is the author of numerous books, including Why Leaders Lie in which he advises leaders to “lie selectively, lie intelligently”.

Also headlining the two-day talkfest was Ray Dalio, a prominent US investor and co-founder of the world’s largest hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, whose book Why Nations Succeed or Fail outlines how weak institutions, rampant corruption and lack of public participation can all undermine a nation state.

Prabowo’s new cabinet ministers – which include figures from across Indonesia’s political spectrum including the outgoing administration of Joko Widodo – were given tips on how to deal with media by a Romanian former journalist turned public relations flack Ana Moraru, and an anti-corruption lecture by an Iran-born Ernst and Young corruption and global crime investigator, Maryam Hussain. Also on the speakers’ roster was Korean-American futurist Hunter Lee Soik, dispensing tips on how to double GDP in a decade.

Prabowo spokesman Dahnil Anzar Simanjuntak told Kompas television on Thursday that the incoming Indonesian president wanted his ministers to have a broader, more international perspective on governance.

“If we want to be a great nation, as Mr Prabowo is advocating, we need strong connectivity with the entire world, and international perspectives help guide our local and domestic steps – think internationally, act locally,” he said.

“That’s why one of the choices Prabowo requested is Ray Dalio (whose) insights are essential for providing an early warning system for successful nations. The principle is that no nation can be great or economically successful if its institutions are weak … characterised by rampant corruption.”

Corruption levels in Indonesia have spiked under the 10-year administration of outgoing president Joko Widodo, whose administration is also accused of weakening democratic institutions. A new poll released this week by Indonesian survey house Saiful Mujani found the quality of Indonesian democracy had declined so markedly under Jokowi that the country was now “experiencing autocratisation”.

“Over 10 years of Jokowi’s government, the level of fear of political speech increased from 22 per cent to 51 per cent, fear of law enforcement’s arbitrary actions rose from 32 per cent to 51 per cent, fear of joining organisations increased from 14 per cent to 28 per cent ... and the perception of constitutional and legal violations by the government jumped from 40 per cent to 52 per cent,” the survey concluded.

Critics of Prabowo have long feared he would take advantage of the conditions he inherited to further undermine Indonesia’s democracy, notwithstanding his appeals to uphold good governance and fight corruption.

Natalie Sambhi, an Indonesia security analyst and executive director of Verve Research, said while Prabowo’s choice of speakers would have provided a “nice pep talk” to his incoming administration, the biggest takeaway from the retreat was that he intended Indonesia to play a greater international role under his presidency.

“Put it this way: getting someone like Mearsheimer in probably signals more that Prabowo is pulling in big names and that Indonesia deserves respect,” Dr Sambhi told The Australian.

“It is more reputational signalling than an indication of foreign policy direction. At the moment, a lot of Indonesia’s problems are domestic and you can’t go solving the world’s problems unless your people are fed at home.”

Additional reporting: Dian Septiari

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout