Can Prabowo Subianto deliver Golden Indonesia?

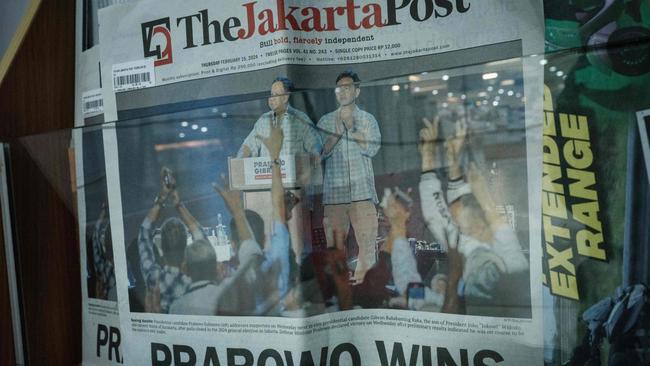

The presumptive new president says he’ll honour Jokowi’s vision – but some fear further erosion of Indonesian freedoms.

It took Indonesia’s presumptive new president Prabowo Subianto a full 10 minutes to thank all who contributed to his storming election victory on Wednesday night, and none received louder, more rapturous applause than former wife Titiek Suharto, daughter of the country’s longtime former autocrat.

Such is the nostalgia for the Suharto era that a deep-fake image of the long-dead strongman – who oversaw the murder of at least 500,000 suspected Indonesian communists – endorsing his former son-in-law was seen as good campaign strategy.

Yet when Indonesians voted in record numbers this week to elect Prabowo as its eighth president it was not to install another strongman in the presidential palace 26 years after turfing out the last. Rather, it was in pursuit of an ambitious economic target that outgoing President Joko Widodo likes to call Golden Indonesia.

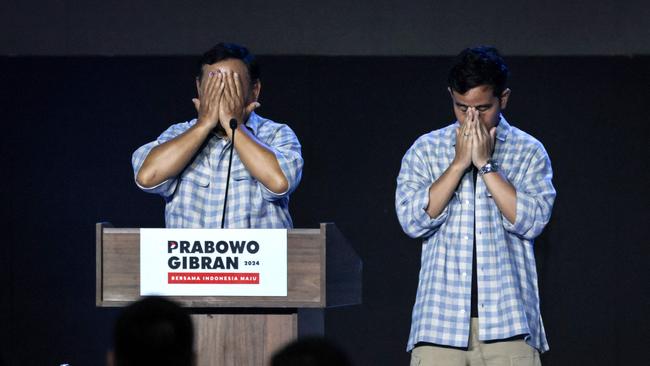

Jokowi’s son Gibran – the country’s 36-year-old presumptive vice-president elect – referred to it at the victory celebration when he credited millions of Indonesians under the age of 40 for Team Prabowo’s unexpectedly high vote haul.

“We did not expect our vote count to be so high but I am sure it is thanks to the young people who want to be part of the journey to a Golden Indonesia,” said Gibran, a man for whom laws were changed so he could run for office.

The country’s reliable election quick counts estimate Prabowo, 72, captured at least 58 per cent of the eligible 204.5 million votes in Wednesday’s polls – the world’s single biggest one-day election exercise – though official General Election Commission results are not due until next month. He will not take office until October.

In reality, Team Prabowo owes its stomping win overwhelmingly to the hugely popular Jokowi, who gave his eldest son his own tacit imprimatur and – critics claim – the resources of the state to help his Defence Minister secure the presidency. The quid pro quo is that Prabowo honour Jokowi’s grand vision for Indonesia to achieve high income status by 2045 and continue the policies that have steered Southeast Asia’s biggest economy out of the pandemic-induced downturn.

Jokowi’s Golden Indonesia is one in which poverty has been eradicated, infant mortality rates slashed, most people can read, unemployment is below 4 per cent and per capita income exceeds $US30,000. It is a huge task, notwithstanding recent efforts to build Indonesia’s industrial capacity through raw commodity export bans that have already drawn billions of dollars of foreign investment into downstream processing, and all but killed Australia’s own nickel industry.

Indonesia has only just regained its higher middle income status after the Covid pandemic knocked millions of people temporarily back into poverty. It averages a respectable 5 per cent annual economic growth but needs to lift that to 7 per cent for a consecutive 15 years to have any hope of reaching its targets.

“Everyone in the Indonesian elite is fixated on this 2045 target of being the eighth richest country in the world,” Bower Group Asia managing director Douglas Ramage says.

“Whether or not they’re doing enough to get there, I know of no one in any Indonesian camp who thinks they should turn away from crucial sources of foreign capital.”

Prabowo knows as well as anyone that such lofty economic ambitions cannot be achieved without providing the stable, predictable environment foreign investors crave. His stratospherically wealthy brother Hashim Djojohadikusumo assured a US-Indonesia business forum last month a Prabowo presidency would continue to encourage downstream processing of its raw commodities to achieve a “new industrialisation of Indonesia’s economy”.

“We also aim to maintain stability which will be fertile ground for foreign and domestic investment,” he said.

Indonesia’s business environment could not be more different to the pre-Jokowi era when foreign investment was something governments turned on and off as needed, set ownership limits and quarantined sections of the economy from foreign ownership, says Ramage, who vice-chairs the American Chamber of Commerce in Indonesia.

“Indonesia today feels and looks more like an India, Brazil or Mexico,” he tells Inquirer. “For the first time the international business community did not let the election impact their decisions because the assumption was whoever won would continue the kind of openness to foreign direct investment we have seen under Jokowi.

“Business had no preference for any candidate but a strong expectation of continuity.”

It also has factored in that “the president-elect has a different personality” to his predecessor, he adds tactfully.

“Prabowo will be his own president. This will not be a Jokowi third term. But no one is arguing against foreign investment.”

Mature democracy?

At a polling station in one of Jakarta’s wealthiest suburbs this week, several educated young voters told Inquirer they had no qualms about a Prabowo presidency, despite longstanding allegations that as a Suharto-era Special Forces commander his unit committed human rights abuses in East Timor, incited deadly riots against Chinese Indonesians, and kidnapped and tortured democracy activists.

“One strongman is not enough to overturn our democracy which is, at this point, already mature enough. There are checks and balances to ensure that what happened here 30, 40 years ago does not happen again,” 24-year-old real estate businessman Aga said.

“I’ve got faith in the strength of Indonesian democracy. People are looking for continuity of the progress that’s already been made. For us it’s quite a simple answer. The Jokowi decade has been good for a lot of Indonesians and there is only one person who’s really capable of continuing that progress.”

Many younger Indonesians express a confidence in the strength of their democracy less readily found in those who lived through the repression and violence of the Suharto decades, or who exalted in early reformasi era achievements only to despair at the recent weakening of democratic institutions under the Jokowi administration.

“In 1998, we didn’t have any freedoms at all,” Harkristuti Harkrisnowo, a University of Indonesia law professor, told Bloomberg this week. “And then we built it up for 20 years. I am worried that we will see a setback in democratic issues with Prabowo as president.”

Prabowo’s fealty to so-called Jokowinomics – which includes a heavy emphasis on infrastructure and push to make Indonesia a global electric vehicle manufacturing hub – is what attracted many young Indonesians for whom better-quality education, jobs, housing and health are more important than any transgressions in the distant past.

At Prabowo’s victory celebration on Wednesday night, supporter Rahmadi Suyuti told Inquirer he voted for Jokowi in 2019 (one of two presidential elections Prabowo lost to Jokowi) but this time backed Prabowo because of his promise to continue his former rival’s economic project.

“Mr Jokowi has many plans but didn’t have enough time to make it all happen – like the fast train from Jakarta to Surabaya and the new capital city (in Kalimantan),” he said. “These are things Prabowo will sustain. I believe 100 per cent he will follow Jokowi’s policies.”

Not everyone is so certain. How long the Prabowo-Jokowi pact endures is already the subject of intense speculation given Prabowo’s unexpectedly large victory.

“The question will be how much Prabowo views that as a personal mandate and how much he sees it as a debt he owes to Jokowi, how long that feeling lasts and how it manifests in doling out posts and strategic positions,” Australian National University politics professor Edward Aspinall says.

Prabowo has promised to assemble a government “consisting of the best sons and daughters of Indonesia”. He is expected to retain Jokowi’s China-friendly stance, particularly on investment and trade, but he will likely be impatient to step out of Jokowi’s shadow.

Like his predecessor, he is aiming for a “big tent” coalition to ease his policies through parliament, though that looks unlikely to include its largest party – the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle – which backed Jokowi’s presidency but on Thursday announced its intention to sit in opposition.

That is bad news for Prabowo but good news for Indonesian democracy, ANU emeritus professor and Indonesia expert Greg Fealy says, given widespread concern over Prabowo’s potential authoritarian instincts.

“Anything that dilutes Prabowo-Gerindra dominance is good for Indonesian democracy,” he tells Inquirer, referring to the presumptive president’s party, which will be only the third largest of a likely eight in parliament.

“It’s probably true that even if he tried to do some sort of radical reshaping of democracy using coercive measures, the forces arrayed against him would overwhelm him. It would just be too risky to attempt it and he will have all of those coalition partners who will want a share of the power.”

The unknowns

Still, Prabowo’s volatility is legendary and a big question is whether he has an inner circle capable of reining him in if things go awry and he begins to give in to his lesser angels. Wen Chong Cheah, a research analyst with the Economist Intelligence Unit, says while Prabowo represents the “strongest continuity of the Jokowi administration … the risk that democratic norms will regress in Indonesia has heightened”.

“Mr Prabowo’s strongman personality and his military past could entail stronger crackdowns on future protests.” He was also the only candidate to be absent from an event in early February organised by the National Press Council where the other candidates pledged to protect press freedom.

His efforts to distinguish himself from Jokowi and allay rumours he was merely a seat-warmer for Gibran “may further exacerbate this”, Wen adds.

John McCarthy, a former Australian ambassador to Indonesia, remembers meeting a young Prabowo months before the latter’s 1998 dismissal from the military for “misinterpreting orders” over the kidnapping and torture of activists, and being struck by his “strong sense of destiny”. “His grandfather was a very senior figure in banking and part of the independence push in the 30s. His uncle was killed fighting the Japanese.”

His father was noted economist Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, who was a minister in the Sukarno administration before a falling-out forced him to take his family into exile in Germany, Malaysia and London, where a young Prabowo graduated from the American School. The family returned to Indonesia a decade later and Sumitro then served under Suharto.

On Thursday, Prabowo scattered flower petals and prayed at his father’s grave.

“If you look at the fact that he has run for vice-president once and president three times, he’s pretty determined. He’s also pretty pragmatic. He has changed partners, been linked with Muslims and fought very hard against Widodo, and yet was able to become his Defence Minister,” says McCarthy. “Now he’s got there I suspect that strong nationalist side will come out. He is not a guy who will be pushed around by anybody.”

Prabowo has issued regular and vague warnings throughout his campaign about the risk of “foreign interference”. On Wednesday night he did so again, telling supporters: “A country as big as ours, as rich as ours, has always been the envy of other powers. Because of that we have to be united.”

Was he referring to China’s persistent incursions into Indonesia’s North Natuna waters to the south of the South China Sea?

On Thursday, Anthony Albanese was the first foreign leader to congratulate Prabowo, outlining in his phone call his “ambition for the future of Australia-Indonesia relations”. Defence Minister Richard Marles, who has been working closely with his Indonesian counterpart to upgrade the defence relationship, also called.

A former Australian government official and Indonesia specialist tells Inquirer Canberra will be counting on a “pragmatic Prabowo, early on particularly, though I’m sure they also know there will be episodes where Prabowo is angry and emotional about things”.

“Just imagine the response if Australia was found to have been tapping his phone,” he says, referring to the incident in which ASIO was accused of doing this to former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Like Donald Trump, Prabowo will take delicate diplomatic handling, “which means we should not just take the next cab off the rank from DFAT as ambassador”, the former official says.

A carefully chosen Prabowo whisperer “with the right set of skills” will be needed to keep the relationship on an even keel.

Only the brave need apply.

with Dian Septiari

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout