It has taken more than two decades of trying, but the 72-year-old scion of an elite Javanese clan will finally fulfil what he believes is his political destiny when he moves into Jakarta’s presidential palace in October.

Make no mistake, the former Suharto-era general and son-in-law of the late autocrat has his erstwhile political rival, Joko Widodo, to thank for an election win that will likely deliver him close to 60 per cent of the vote by the time the formal count is completed next month.

The hugely popular outgoing President – who spent months exploring ways to circumvent a constitutional bar serving a third term – gifted Prabowo his eldest son as running mate, his own tacit imprimatur and the resources of the state to lift him to victory.

The quid pro quo is that Prabowo honours Jokowi’s grand vision for Indonesia’s path to high income status by 2045 and continue the policies that have ably steered Southeast Asia’s biggest economy out of the steep pandemic-induced downturn.

It is a massive task and one could argue Indonesia is not yet doing enough to realise those ambitions, notwithstanding raw commodity export bans that have attracted billions of dollars in downstream foreign investment and, in the process, all but killed off Australia’s own nickel industry.

But no country can achieve such lofty economic ambitions without creating the stable and predictable environment that foreign investors crave, and Prabowo will be mindful of that.

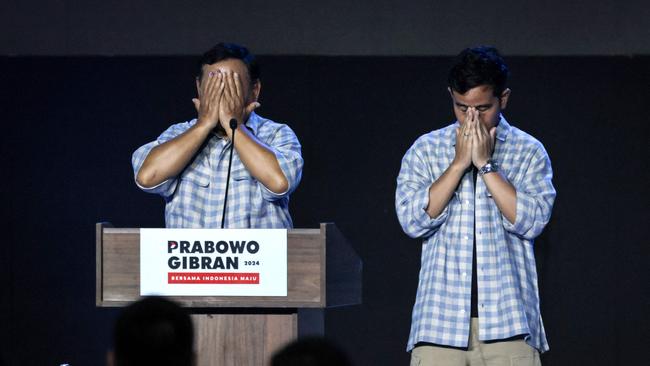

In his victory speech in central Jakarta on Wednesday night, he talked of reuniting the country after a bruising election contest and building a government that can get on with that task.

This is what Indonesians want, and to get there they were willing to overlook the deep flaws and past offences that have caused voters to reject Prabowo in five previous consecutive elections.

This time around the feared former general was offering continuity, not a return to the so-called glory days of autocracy or a 1945 constitution that would wind back Indonesia’s prized democracy.

It is easy to overlook the singular achievement of Indonesia in busily pointing out where it has gone wrong.

A quarter-century ago it was a nation in violent turmoil, on the brink of financial collapse.

That it has just pulled off the world’s largest and most complicated one-day election and done so safely, without violence and in a manner that was – notwithstanding the accusations of bias against Jokowi – largely free and fair is cause for celebration.

Indonesia will be of course be different post-Jokowi – perhaps more hierarchical, less predictable, maybe even less shy of projecting itself on the global stage.

Prabowo has none of the easy “man of the people” mien that has made Jokowi Indonesia’s most popular leader. He will always carry the stain of a dark past.

The allegations that led to his 1998 dismissal from the military – that he led a special forces unit that committed atrocities in East Timor and West Papua, and kidnapped, tortured and disappeared democracy activists – have not gone away.

But his campaign was all about convincing voters that he had mellowed, learned lessons, and was ready to lead.

As Indonesia’s next president, Prabowo has promised to govern for all – “whatever their tribes, ethnicities, race, religion, whatever their social or economic background” – and to lead the country forward.

“Great nations always look ahead, embracing their future,” he told jubilant supporters on Wednesday night.

Given the likely size of his mandate, he now has the right and the responsibility to prove that he will do what he has promised.

That Indonesia fulfils its ambitions is as much in Australia’s interests as it is its own.

For all the warnings that Prabowo Subianto could usher in a new era of authoritarianism in Indonesia, the Defence Minister and former strongman has won a stomping mandate to govern the world’s third-largest democracy.