China’s attitude to outsiders plummets

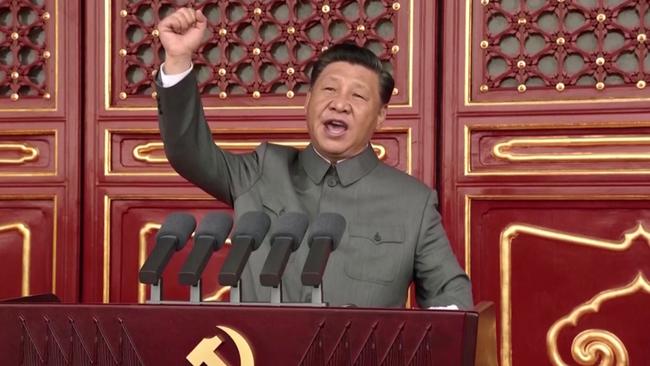

Under Xi Jinping, working with foreigners, or introducing international perspectives, is no longer a route to elevation.

During the 35-year reform era launched by Deng Xiaoping, people who built firm contacts with foreigners – ranging from academics infusing their research and teaching with invigorating inputs from global peers, to city leaders attracting international investors who boosted local growth and prosperity – often were rewarded and lauded. During the New Era of Xi Jinping that is steadily being reversed.

It would be foolish to suggest China is cutting itself off from the world. But working with foreigners, or introducing international perspectives, is no longer a route to elevation – which means those of us with Chinese friends and professional and business contacts need to work that much harder to stay in touch and stay supportive.

There is now no advantage to be gained within China, in terms of appointments, promotions or networking, by presenting oneself as especially internationally connected. This is the case even, rather oddly, if one is a diplomat.

China’s ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, said recently: “Westerners accuse us of not conforming to diplomatic etiquette, but the standard for us to evaluate our work is … how people in China look at us … not whether foreigners are happy or not.” The Foreign Ministry’s party secretary Qi Yu has instructed that diplomats should “be brave and good at fighting”.

The 196 Chinese intellectuals who have visited Japan in an exchange program arranged by the Japan Foundation have been widely vilified as “traitors” on Chinese social media.

Jack Ma provides another telling example. The founder of online octopus Alibaba became, by entrepreneurial brilliance and then global connectedness, the best known Chinese person in the world – initially more than Xi. He famously kept in touch with Ken Morley from Newcastle, NSW, who after a chance family meeting became an important mentor. Ma donated $26m to the University of Newcastle to encourage students’ globalising ambitions.

He recently has been humiliated by Beijing, starting with the sudden halt of a $50bn float to spin off Alibaba’s finance business. He had become too big for his boots. It was imperative that he acknowledge that however feted he might be worldwide, in China there was room for only one outsize personality and one outsize, pervasive organisation.

The rewards, in terms of party affirmation, increasingly go to those who err on the side of caution and of distancing – or even downright suspicion – concerning international relations.

People’s Daily, which always leads the party zeitgeist, has warned that “a spy might be an intimate lover, a warm-hearted person who offers you a chance to earn money, or an online friend with the same interests”.

The Ministry of State Security has introduced regulations that, according to Li Wei, a national security expert at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, “place emphasis on companies and other institutions taking precautionary measures against foreign espionage”.

Such anxiety has percolated down to comparatively remote localities. Jude Blanchette, who holds the Freeman chair in China studies at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, has translated a lengthy document warning against existential risks identified by the Communist Party committee of Niangziguan, a town of 11,500 people almost 400km southwest of Beijing.

This insists the town “strictly prevent overseas intelligence personnel from … travel and tourism or economic and cultural exchanges to steal core secrets … Strictly prevent overseas NGOs, as well as certain domestic social organisations that receive Western support, from going around under the banners of ‘democracy’, ‘human rights’, ‘religion’, ‘charity’, ‘environmental protection’ and ‘poverty alleviation’ … Crack down on illegal Christian infiltration activity … Prevent manipulative interviews and malicious provocation by foreign media … Prevent hostile forces from targeting young students with Western misconceptions and conducting ideological infiltration.”

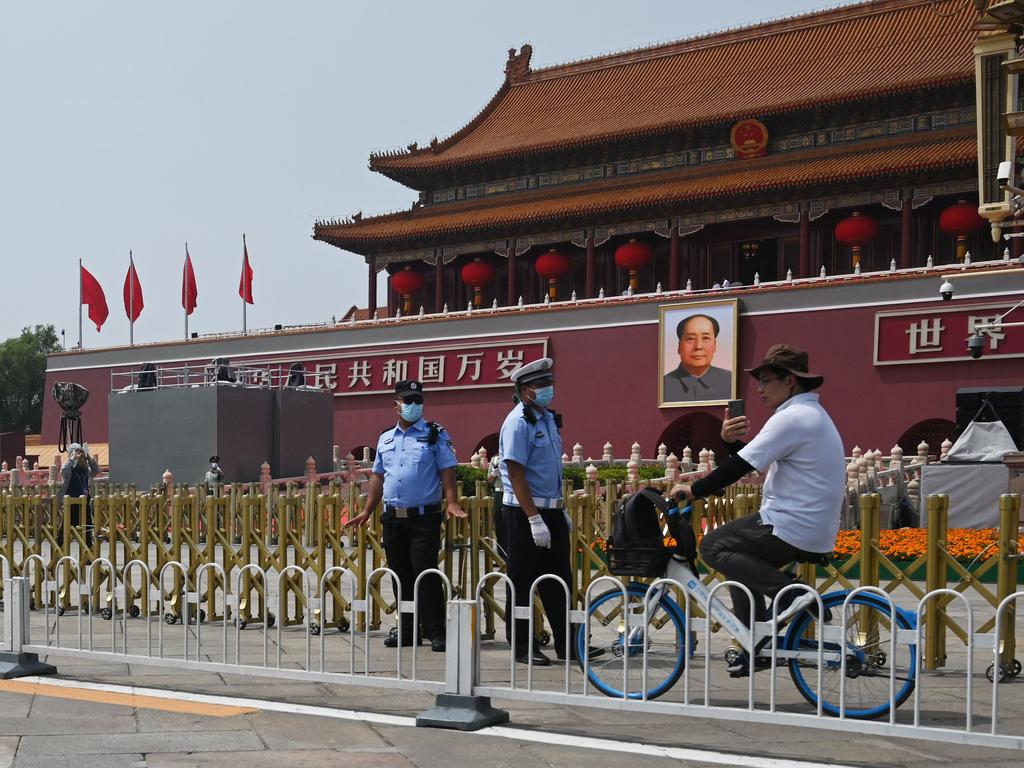

In Hong Kong, the National Security Law imposed by Beijing a year ago – the core mechanism for bringing the city to heel – links international connectedness with subversion and threat. “Endangering national security” is defined very broadly, including “provoking hatred” towards the ruling Chinese Communist Party, and “collusion with a foreign country or with external elements” is equated with terrorism.

The slew of arrests and jailings of journalists in Hong Kong and the closure of the last significant opposition publication in Chinese, Apple Daily, enabled by the security law’s vague clauses attacking “foreign collusion”, are closing the curtains on the city’s former role as a model of cosmopolitanism.

Global Times, a CCP publication, asserted that Hong Kong’s “status as a global financial hub hasn’t faded”, yet chiefly adduces as evidence its continuing use by mainland Chinese business and students.

Diversity is less celebrated now even within the People’s Republic of China itself. Xi champions “the spirit of the Zhonghua nation”, which in practice tends to approximate the dominant Han culture and its Mandarin language, to which Uighurs, Tibetans and Hong Kongers are increasingly required to assimilate.

For Australia, whose multiculturalism and immigration mark two key differentials from the PRC, it’s valuable to recall at this time Gough Whitlam’s breakthrough meeting with Zhou Enlai.

But it’s also necessary to focus on the current governance and ideological realities. This is not 1971. Our relations with Richard Nixon, Nikita Khrushchev or Suharto don’t provide much of a guide for dealing with the US, Russia or Indonesia today.

Rowan Callick is an Industry Fellow with Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

The rapid dismemberment of Hong Kong’s lively and internationally facing culture points to a bigger story. That is, that the same suspicious attitude to the outside world and the same introversion also has been growing, in a less time-compressed way, in mainland China.