Many millions more Chinese would join the party if they could, not necessarily from ideological conviction but because Communist Party membership is such a career boost. Yet we shouldn’t discount the power of communist ideology.

I had a spell as a Visiting Fellow at Kings College London in 2019. One night I attended a dinner party where everyone was an author or academic or journalist. They weren’t China specialists, but wanted to hear an Australian view of China.

When I discussed communist ideology, the reaction was bafflement. Wasn’t modern China capitalist, and any communist gobbledegook merely an excuse to justify authoritarianism?

No, no, no, no – that’s a characteristic Western view. And it’s dead wrong. One way the West misunderstands China is by misunderstanding the CCP. The contemporary Western mind cannot credit belief in anything but liberalism or, now, sybaritism.

Thus many Western commentators couldn’t believe that Islamic State and al-Qa’ida had genuine religious motivations. It’s why Asia, where religious belief is everywhere, is still such a mystery to the West.

The CCP is a paradoxical, complex, elusive and analytically difficult beast. This columnist is as anti-communist as you could reasonably be, but let’s leave aside for the moment the CCP’s shocking human rights abuses, and similarly its huge positive achievement of raising so many people out of poverty.

Let’s approach from a different angle. One prism for understanding the CCP is to think of it as a nationalistic, religious movement that controls state power. Like most religions, it is born of specific historical circumstances, which shape its character today. It is only 100 years old, but, a little like the Catholic Church (with obviously no moral equivalence) it has maintained an astonishing degree of cultural continuity.

Communism is a Western ideology imported into China. It should have been starkly unappealing. At the party’s first meeting in Shanghai, there were two representatives of the Third International, later the Comintern, the Moscow-directed international communist movement. The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 was a huge inspiration to the Shanghai comrades. Although Chinese don’t emphasise it now, for several decades the CCP took ideological direction, and a lot of money, from Moscow.

The CCP began with a strident hostility to the West, partly because the Treaty of Versailles gave Chinese territory that Germany had occupied to Japan.

Geremie Barme, the most brilliant of contemporary Sinologists, stresses the importance of Stalin in the development of the culture and historical purpose of the CCP.

When Barme first visited China in the mid-1970s, there were many pictures of Stalin and his works were compulsory reading. Although an atheist from childhood, Stalin attended a Russian Orthodox seminary and studied many church-related subjects. In grossly distorted fashion, he transfused some religious organisational forms, such as the confessional, into communism.

One of Marxism’s economic precepts is that private property should be abolished. When this is not followed, outside critics mistakenly dismiss Marxism altogether. But the official ideology of the Soviet Union was Marxism/Leninism. A key to Leninism was the absolute supremacy of the Communist Party, the drive for the party to seize and hold state power and to transform theoretical principles of Marxism into living reality.

The great theoretical innovation of Mao Zedong was to substitute China’s rural peasantry for the industrial working class of Marxist Europe. Communist parties were meant to be proletarian parties – but as an overwhelmingly rural society, China didn’t have a proletariat.

Mao’s innovation came to stand for the CCP generally adapting Marxism/Leninism to Chinese circumstances.

Liu Shaoqi, Mao’s long-time deputy and author of the rib-tickling bestseller How to be a Good Communist, was the first to coin the term “Mao Zedong Thought”. The CCP’s official ideology thus became Marxism/Leninism/Mao Zedong Thought. Liu, by the way, ultimately fell out with Mao and was, naturally enough, purged, repeatedly assaulted and killed in the Cultural Revolution after being denounced by Zhou Enlai as “a renegade, traitor and scab”.

Later, posthumously, Liu was rehabilitated by Deng Xiaoping – and even Xi Jinping has given speeches in his honour.

The history of communist China from 1949 to 1979 was astoundingly turbulent and bloody. The party briefly encouraged open criticism in the Hundred Flowers campaign in 1957 but then brutally crushed all its critics in the Anti-Rightist campaign that followed straight after, and killed probably millions of people.

Mao then implemented the Great Leap Forward, which was supposed to make China self-reliant and truly communist but led instead to the Great Famine, which killed tens of millions of people. And then, partly in a power struggle within the leadership, but also partly to try to bring the party back to its revolutionary roots, Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution from 1966 for 10 years in which, again, tens of millions died, starved, were killed or just generally persecuted.

Here’s a clue to how this history affects China today. Xi, though he suffered in the Cultural Revolution, is devoted to Mao, making sure Mao stands high as a hero of modern China. Mao, Xi and other communist leaders are almost deities, like the emperors of ancient Rome. Modern communist leaders typically acknowledge the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were mistakes, but see them as part of “strenuous experimentation” in working out the true meaning of Marxism/Leninism/Mao Zedong Thought.

Xi, and the CCP, see modern Chinese history as three neat sections. The 30 years from 1949 to 1979 is the period when China stands up, and belongs to Mao. From 1979 to 2009 is the reform period when China becomes wealthy. It belongs to Deng Xiaoping. The third period, from 2009 to 2049, is when China becomes the world’s dominant power. It belongs to Xi.

The things Chinese leaders say in global forums are not a reliable guide to their future actions. But the things they say to their own people are profoundly important. Xi speaks often in quasi-religious tones to his folks, especially his soldiers, promising them a future both of glory and struggle against the enemies of the Revolution and the CCP. Chinese actions in this view always serve the highest morality of history’s purpose.

Don’t think Chinese communists do not believe what they proclaim. People with deep beliefs, whether friend or foe, are generally the most formidable actors in history.

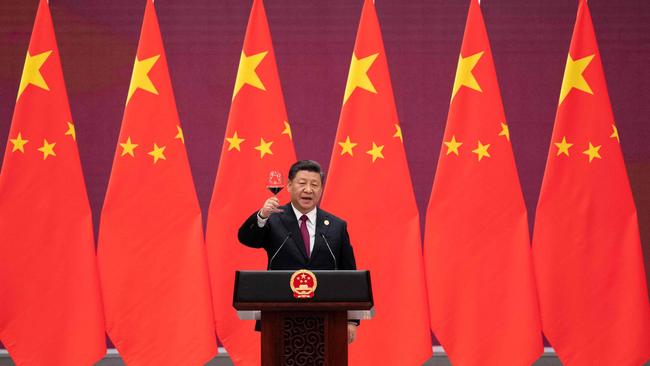

The Chinese Communist Party turns 100 on Thursday. It is the most powerful, and successful, political party in the world. It has something like more than 90 million members and has ruled China since it won the civil war in 1949.