But while it has abandoned the Marxist utopia, the CCP is more wedded than ever to the Leninist matrix from which the party sprang. Adopted at the Communist International’s second congress, which was held in Petrograd and Moscow between July 19 and August 7, 1920, “the twenty-one conditions” the nascent communist parties had to meet for admission to the Comintern, and the “six elements” into which Stalin crystallised those conditions in 1924, remain the CCP’s defining characteristics to this day.

In particular, each party was to be to be organised “in the most centralised way possible and governed by iron discipline”; it was to undertake an “absolute rupture with reformism” while purging any bourgeois weaknesses “that worm their way into it”; and as “the vanguard of the working class”, it was to be the “instrument of the dictatorship of the proletariat”, seizing and retaining an absolute monopoly on state power.

It is true that during the period from the Long March in 1934-35 to the initial canonisation of Mao Zedong Thought in the Rectification Campaign of 1943, Mao “Sinified” some aspects of the Leninist model.

However, the enduring consequence of the Sino-Soviet split, and of the acrimonious exchanges that pitted the CCP against the Soviet “revisionists” after the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s 20th Congress in 1956, was to cement in the CCP an even more doctrinaire vision of the Leninist party than that held in the Soviet bloc.

Moreover, both the chaos of the Cultural Revolution and the collapse of the Soviet Union (which the CCP blamed largely on the CPSU’s lack of ideological resolve) only strengthened the CCP’s insistence on the “primacy of the party”, with the commitment to crushing anything that might undermine it being the hallmark of Xi Jinping’s leadership.

As a result, although the CCP has, since taking power in 1949, experienced more frequent and more abrupt changes in course than any of its sister parties, its myriad swerves have masked an impressive continuity in the party’s conception of its role and purpose.

Underpinning that conception is a Manichean view of the world, in which “the most fundamental fact” is – as the CCP put it in deriding the long-term possibility of “peaceful coexistence” – “the antagonism between the imperialist bloc of aggression and the popular forces in the world”.

Nor is that antagonism – which has led “the leader of the imperialist camp, the United States” to be “especially vicious and shameless in obstructing China’s liberation of its own territory, Taiwan” and “to openly adopt subversion” as its “official policy” – ever likely to subside.

On the contrary, as Mao explained in 1975 to a sympathetic Pol Pot (who was in the throes of launching the genocidal policies that would kill a quarter of Cambodia’s population), socialism’s struggle with its enemies would last 10,000 years. Indeed, much as Stalin had predicted at the so-called Congress of Victors in 1934, the attacks on the “dictatorship of the proletariat” would intensify as “the imperialist camp” felt increasingly threatened by socialism’s inevitable progress and by capitalism’s equally inevitable decline.

That, the CCP wrote in its vastly influential tract On the Historical Experience of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, was why “the counter-revolutionaries, bent on attacking our cause, have always demanded that we ‘liberalise’ ”: those “who prate about ‘democracy’ are, in effect, opposing socialism”. And it was also why Lenin’s statement that “allowing freedom of the press amounts to suicide”, would remain true indefinitely.

Rather, the achievements of the Chinese revolution could be secured only by deploying “mercilessly rigorous, swift and resolute force”.

But while the CCP has never hesitated to rely on violence, it is obvious that repression alone cannot provide the legitimacy stable and effective rule requires.

Since economic reform began in 1978-79, that legitimacy has been secured mainly through the party’s ability to deliver spectacular improvements in living standards, lifting millions out of abject poverty. However, growth rates of productivity have dropped sharply, and are likely to decline further as the party expands its control over business and moves to prevent entrepreneurs from emerging as a competing power base. As for the desire for stability, which has provided the CCP with a second major source of legitimacy, it too may prove a less effective justification for authoritarianism once the anarchy of the Cultural Revolution fades into the distant past.

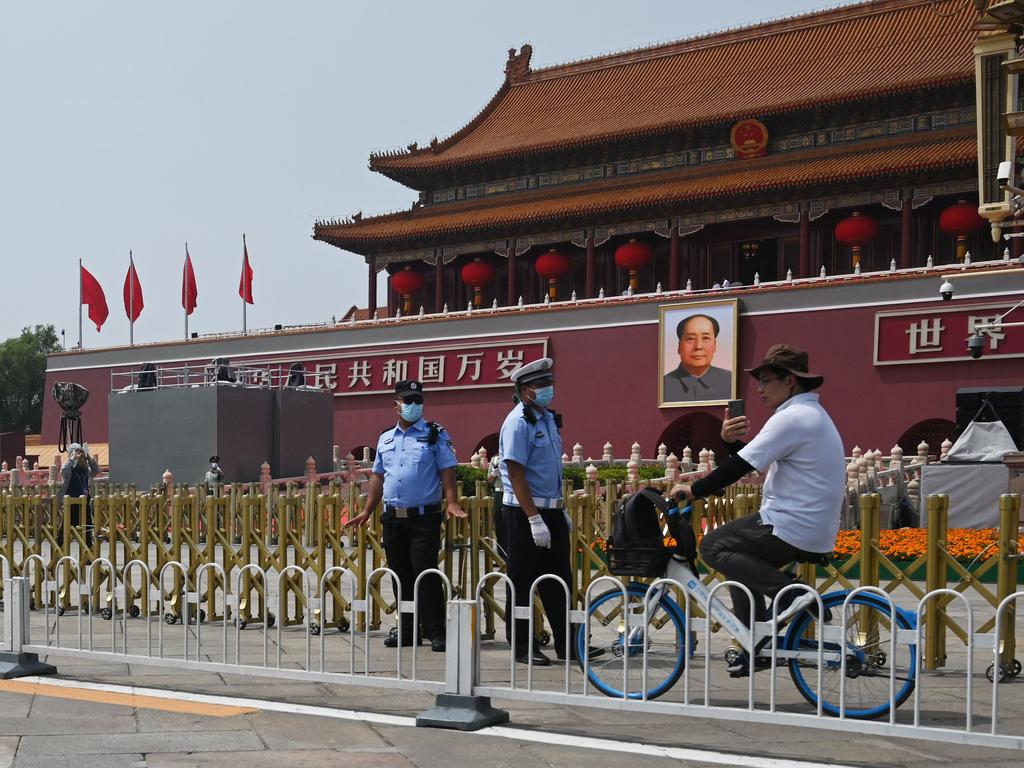

Little wonder then that the regime, in its search to bolster popular support, has turned to a belligerent nationalism that has always been incipient in its “bloc against bloc” theory of international relations, which demonises those countries it views as China’s adversaries. And little wonder too that it has resurrected the cult of the personality, giving Xi a status – and a degree of personal power – surpassed only by Mao.

Yet those strategies are replete with risks – and their combination compounds them. No one understood that better than Khrushchev, who was exasperated by the insults the CCP hurled at him. The cult of Mao, he astutely observed in 1961, induced Chinese officials to prove their loyalty by acting even more aggressively than Mao did. Confusing stridency with substance, their “endless swearing at imperialism and revisionism” betrayed “a sort of voodoo belief in the power of curses and incantations”, deepening every conflict and vitiating every attempt at productive discussion.

And the CCP itself also noted the dangers, in an implied criticism of its record of tumultuous policy instability. While “the dictatorship of the proletariat requires a high degree of centralisation of power”, it wrote in reviewing the Stalin era, “when there is an undue emphasis on centralisation, many serious mistakes are bound to occur” – mistakes made all the more certain by the cult of the personality, as “eulogies turn the leader’s head”, discourage him from “listening carefully” and induce hubris and “subjectivism”, with disastrous consequences.

Unfortunately, far from heeding those lessons, the CCP is erasing them from the history books – just as it is seeking to erase the memory of the 35 million Chinese citizens conservative estimates suggest it sent needlessly to their deaths. More powerful yet also more paranoid, than ever and trapped in a Leninist mindset that has repeatedly plunged the Chinese people into untold misery, it is doomed to remain, for Australia and the West, an unreliable partner and an impossible friend.

As the Chinese Communist Party celebrates its centenary, the goals at the heart of Marxism – of achieving a world in which private property and commodity exchange have been abolished, the state has “withered away” and resources are allocated on the basis of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” – scarcely figure in its program.