Patiently awaiting their turn, there is next-to-no hesitancy or any delay in accepting the jabs: surveys show across the UK just six per cent of people are reluctant to be vaccinated right now. Of that very small number, a few say they just want a bit more time to gain confidence in the vaccine process.

The broad, almost universal acceptance of getting the vaccine – not once, but twice – even in the midst of worries about extremely rare side effects – has been extraordinary.

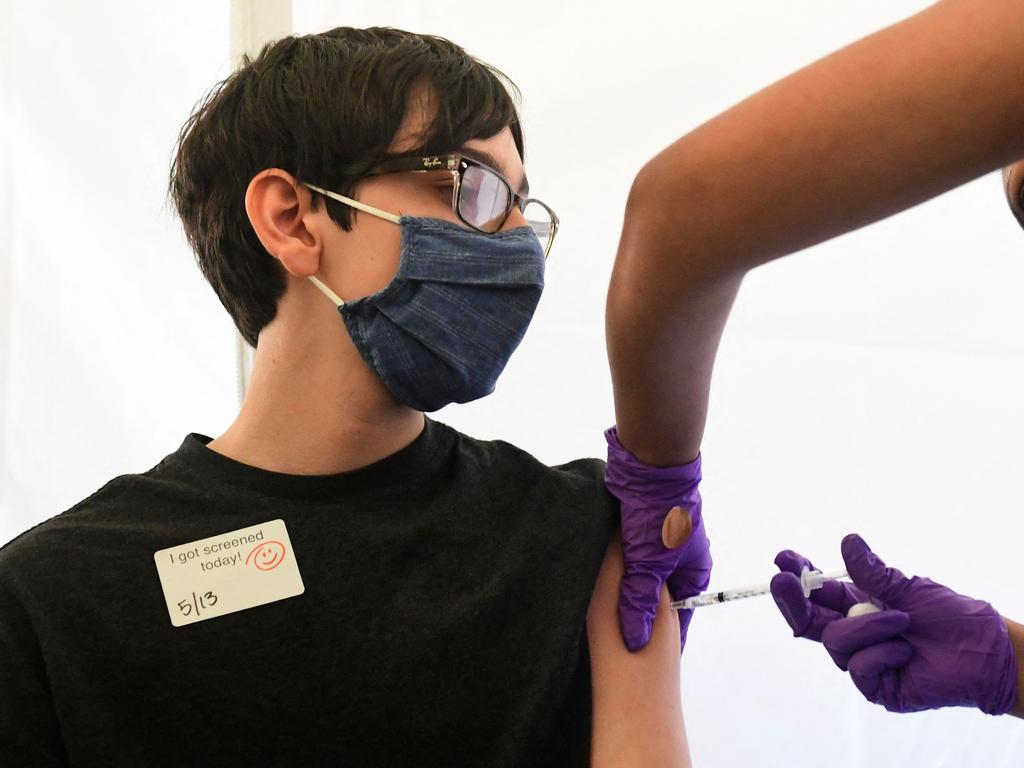

More than nine in ten Britons want the vaccine, any vaccine. Unlike in Australia, there are no demands here for a particular brand, indeed most people here don’t know what variety they will get until they have exposed their arm for a jab from the doctors, nurses, vets, and even students and health administrators who have undergone special training. Only recently the government advised that under-40s will be offered an alternative to AstraZeneca.

I received AstraZeneca in a re-purposed medical centre; my partner got his, the Moderna shot, in the open air at a Wimbledon football stadium. A friend got a Pfizer inoculation at the science Museum while marvelling at the Wellcome Galleries exhibit detailing developments in vaccination, a year after the world first heard of this new virus.

Getting vaccinated is seen across Britain as the only way to minimise the risks of getting coronavirus, and then if you do contract it, of suffering less debilitating effects. It is perceived as the quickest route for the wearisome coronavirus countermeasures to stop. The more the vaccine has rolled out, the more popular it has become: the vaccine acceptance rate was just 78 per cent before Christmas, whereas now it is 94 per cent.

Interestingly the fear of the virus here – everyone is just getting on with life – is reasonably low, mirroring the very low vaccine hesitancy. But in Australia where there is high anxiety there is corresponding higher levels of vaccine hesitancy.

Dr David Comerford of Stirling University said people dread outcomes more than they negatively experience the outcome when it comes around.

“People over-estimate how negative it may be. the sense of threat and menace from this disease that is all out there in world but not yet here (in Australia) would induce chronic fear and anxiety and almost persecution,” he said.

“At some point the borders will give way, and until it does Australians don’t see the immediate need to get vaccinated and especially when the vaccination does have minuscule risk of blood clots. Those stories have not helped.’’

A quarter of Australians have indicated they won’t get the vaccine because of the international border closures isolating the country and a fear of side effects.

This is then coupled with the vaccine rollout being one of the slowest in the developed world.

The Australian Medical Association fears Australia is a “sitting duck’’ over the coming months if coronavirus does infiltrate the country.

“I wonder at peoples’ capacity to have two incompatible beliefs and governing behaviour … you can know the inevitable and put your head in the sand and not take action to mitigate it,” Dr Comerford said.

In the UK, the success of the vaccination rollout, and the development of the cheap, home grown Oxford-AstraZeneca collaboration, is a source of post-Brexit national pride. Across the English Channel, Europe has been botching its orders, trying to stealthily acquire vaccines contracted by others, including Australia, while Britain has just got on with it.

The UK media is almost universally supportive and anti-vax sentiment is almost non existent. When high profile England rugby player Henry Slade, who is an insulin dependent diabetic, expressed concerns, it became front page news.

Anecdotally it appears that if you have been exposed to the coronavirus beforehand, side effects from the vaccinations are heightened. Scientists believe the immune response of people previously exposed results in more whole of body reactions, such as fatigue, headache, chills, fever and pain over several days.

Yet Britons have largely ignored the hysteria over AstraZeneca – trusting implicitly in the home grown product and well intentioned Oxford scientists and then have stoically faced a high chance of feeling unwell for a short period – twice – in order to be double vaccinated.

As of June 1, over 75 per cent of adults have received their first dose and 50 per cent have received their second. A phenomenal 66 million doses have been distributed by the National Health Service in six months.

There are no forms to fill in, only a simple link in a text message to click to choose a day and time to turn up. The eligibility to receive the vaccine has been clear and easily understood, based on age and vulnerability. Last week was for the 30s and over; in the coming weeks it will drop to 28 and 29 year olds to book their timeslots. While the UK also took a punt on delaying the second vaccination as much as three months in order to prioritise first doses; the time gap between jabs is narrowing now to eight weeks. My second vaccination took three minutes 38 seconds from walking in the door, having the jab and walking back out.

In places such as Bolton, Brighton and Redbridge, or areas where the vaccination rate has dropped, highly visible vaccination buses take the vaccines into the heart of communities.

In Redbridge, the bus – seen as “a familiar and friendly entity’’ operated into the twilight to coincide with Ramadan.

Dr Helen Wall, clinical director of the Bolton Covid-19 vaccination program, said the bus created “quite a buzz’” as people turned up in droves to get vaccinated without an appointment.

In areas where coronavirus cases are increasing, Downing Street has begun a blitz, deploying thousands of additional vaccine doses. At Twickenham Stadium, west of London, 15,000 people received a Pfizer vaccine last Sunday, and vaccine age limits were abandoned. Tim Vizard, Public Policy Analysis, Office for National Statistics said that people were increasingly positive about the Covid-19 vaccines. “Of those who are hesitant about receiving the vaccine, it’s younger and black adults who are most likely to say this, with concerns around side effects, long term effects and how well the vaccine works being the most common reasons.” Statisticians have also found that of those who are hesitant, about 10 per cent are pregnant women, or women of child bearing age. Everybody else it seems, is sticking their arm out at the first possible opportunity.

For many months now, millions of Britons have arrived at sports stadiums, pharmacies, halls and even the science Museum and Poets Corner in Westminster Abbey for coronavirus inoculations.