Our children are the ones now suffering the most

We were sitting in the kitchen doing what Victorian families do now: staring at devices, in this case laptops. I was doing what loosely might be described as work, my daughter what is risibly designated “remote learning”.

But just for an instant, she forgot quite where she was. She was chortling away like kids do when teachers look silly to them; they were pulling faces, making gestures; it was like she had slipped through the screen, was actually at school.

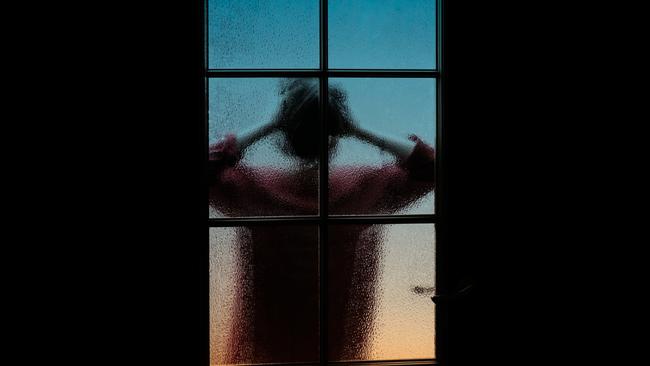

Then, as I looked on, my daughter pulled herself up, realising where she was. She wasn’t with her friends; she was learning little if anything; she was being distracted momentarily from her miserably confined life by technology. Her face fell. She retracted into her chair. She’d been fooled and she was angry, at no one in particular, although her father was nearby and he’d do.

If you’re not a Victorian parent, you’ll have little grasp of what I’m describing; if you are, you’re not alone. We are legion, we fenced-in, fed-up families, into our fourth lockdown of lies that distance education is any substitute for the intimate kind – when, on the contrary, it is an instrument for reminding us what we’re missing out on.

Every day of this fourth lockdown is an emotional struggle, never mind an intellectual one. I know parents who’ve just given up. I know teachers going out of their minds. Most of all I hear of kids who are devastated, after their five minutes of Dan-earned sunshine, to be plunged back into this sterile mindf..k of screen-based busywork.

My daughter and I have at least been able to talk about it a little. Yes, she’s been feeling upset, but can’t explain why: it’s nothing specific, everything in general.

I shouldn’t ask her about it, she advises, because this unsettles her more – good advice, from one wise beyond her 11 years.

But what can a protective parent do when the subject of his worry is right there, all the time, internalising all sorts of bad lessons? That includes a worsening apathy, an aversion to groups, a dread of going outdoors, and a sense of education as a hollow sham.

GIDEON HAIGH ON LOCKDOWNS

No gratitude, no pride, no relief: just quiet seething

As the world’s worst lockdown ‘ends’ (it hasn’t), it’s time Daniel Andrews knew how many of us in Victoria feel as we watch his sickening pivot.

In alienation, anger all we have left in common

Lockdowns prevented us from going to one another’s aid; now we have lost the instinct.

Like a commercial My Lai, we’re destroying the village to save it

We’ve all experienced the stress of last-minute cancellations, the fatigue and apathy that attends any effort not directed at simply getting through a day.

Our children are suffering the most

Something got lost early on in the fight against Covid in the message that our most vulnerable are the elderly rather than our children.

Saving old lives just to ruin young ones

Every day, Daniel Andrews sends proforma condolences to the families of people who have died in their 80s and 90s. But what about the harm to our children?

We’re luckier than most. Our school has striven valiantly. We have a spare old laptop. I keep remembering a conversation in a doctor’s waiting room early in Lockdown 1 with a Sudanese woman from the local commission flats, who had seven children and one tablet. I’ve wondered ever since how she has coped.

Something got lost early on in the fight against Covid, in the message that those most vulnerable were the elderly, which resonated with the guilt many feel about having to surrender daily responsibility for their parents to aged care. We lost focus on those most dependent and most vulnerable: our children.

You sense it at every media conference: the parade of mediocre middle-aged white men participating in the charade that a state can be turned on and off at a whim, with their self-dramatising spiels about the virus being a “beast” that has to be “brought to ground” as though they’re about to enter the jungle with beaters and pith helmets.

There speaks the unshakeable confidence and unexamined privilege of men who know that someone else (a woman, a young person, another minion etc) will do the fiddly stuff for them – the caring, the teaching, the fetching and carrying.

James Merlino seems to have forgotten that he’s Education Minister, imagining instead that he is Churchill or, more impressively, Dan Andrews.

The Victorian government will insist they have factored in the toll on children of the abruptly blank fortnight, but it is way down the list of priorities compared to that index of virtue, the daily case number – or perhaps the paramount metric, the government’s approval rating.

Because of the very modern mentality that what cannot be measured does not exist, the educational and social setbacks of the young are as nothing by comparison.

Someone should be speaking for our children. It is their world more than ours. They have more time on earth ahead of them than we do – and what a stupid, selfish, screwed-up, angry ash heap we’ll bequeath them.

Afterwards I was sad for my daughter, but also kind of proud, in that she could see instinctively through the hoax she was being sold – ie, that technology can deliver a meaningful educational experience.

That’s the great and also very confronting thing about children. They have no guile. They won’t suffer in silence. They haven’t learned to lie and dissemble the way we have; they wouldn’t know how to spare our adult feelings even if they wanted to.

They are telling us that we can no longer live this way. And it’s about time we listened.

One minute she was there; the next she was not.