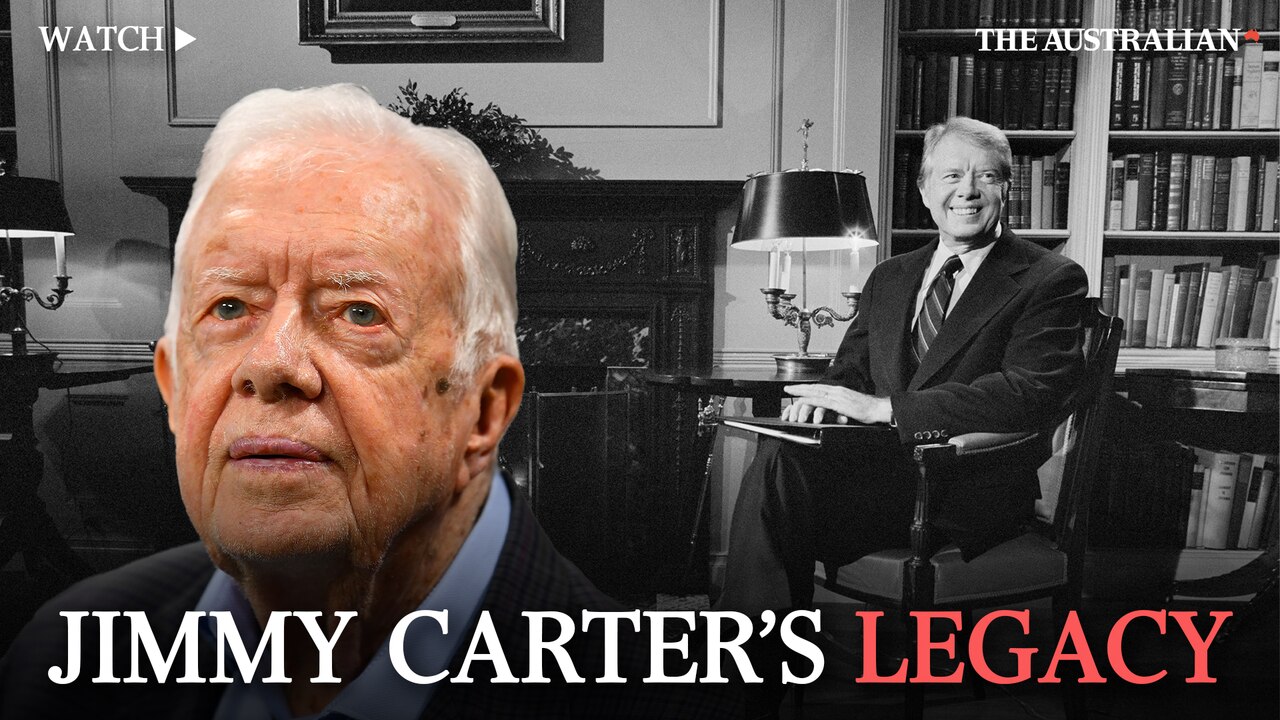

A very good man who turned out to be a very bad president: the facts about Jimmy Carter’s legacy

Jimmy Carter was a man of decency, character and principle. But his presidency suffered from two problems: America’s enemies didn’t fear Carter, and America’s allies couldn’t rely on him.

He was a man of decency, character and principle. It’s right that his long life of service to the ideals he believed in, his personal decency, his character in an era not over-endowed with political leaders of character, should be fully honoured by his nation, and by everyone who values integrity.

It’s also important that we honour the facts.

And the facts are he was a very poor president. He was incompetent at running his own administration and almost all his policy instincts, domestic and foreign, were wrong.

He had one outstanding achievement – brokering a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. That was a huge achievement and it’s the one big plus of his presidency.

But there were plenty of minuses.

Many of them stemmed from two simple facts. America’s enemies didn’t fear Carter, and America’s allies couldn’t rely on him.

At one point he announced the complete withdrawal of all US forces from South Korea. This would have destroyed the US alliance system in Asia when the Soviet Union was still strong and China had recently been sponsoring communist insurgencies in Southeast Asia.

There was very little sense Carter knew what he was doing or understood the nature of the adversaries America faced.

A little later, Carter was shocked that Moscow in 1979 invaded Afghanistan, famously saying he’d learnt more about the real nature of the Soviet Union in a few days than he had previously ever known. Which demonstrated not his capacity for learning but that he never understood the nature of the Soviet Union in the first place.

Similarly, Carter’s proclaimed emphasis on human rights bore no effective consequence for big, hard, powerful communist nations like the Soviet Union or China, but was brought to bear on very difficult US partners like Iran under the shah. Carter was indifferent to the collapse of the shah’s regime and Iran has since groaned under the quasi-totalitarian religious dictatorship of the ayatollahs.

Iran has become the world’s biggest state sponsor of terrorism, continually wreaks havoc throughout the Middle East, sponsors many attacks on US forces and is on the brink of acquiring nuclear weapons.

Being exasperated about the CIA dealing with dictators is one thing. But foreign policy in the real world is routinely the choice of the lesser evil. No US policy maker today is unhappy the army runs Egypt again, as opposed to the short-lived reign of the Muslim Brotherhood when Hosni Mubarak’s regime fell.

Carter never displayed much realism about anything. Until the world was collapsing around him towards the end of his presidency, he’d favoured cutting US military expenditure.

There’s a suggestive parallel between Carter and Joe Biden, and Donald Trump and Ronald Reagan.

Anyone who wins the US presidency is at some level formidable. But Carter’s 1976 win was very narrow. After all the scandals of Watergate, Vietnam and the forced resignation of Richard Nixon, Carter barely beat Gerald Ford, 50 per cent to 48 per cent. Carter won fewer Electoral College votes than Trump did in November.

Four years later, Carter was annihilated by Reagan, who beat him by 10 per cent, 51 to 41, and 489 to 49 in the Electoral College.

Here’s where the historical parallels are suggestive. The Iranians took 66 American diplomats hostage in 1979 and kept them hostage for the rest of the Carter presidency. A US military effort to rescue them under Carter was a fiasco. The Iranians immediately released the hostages when Reagan took office. They were scared of Reagan. No one was scared of Carter, just as no one was scared of, or deterred by, Biden.

Of course, Reagan was an infinitely better man, and president, than Trump. But like Trump he projected political clarity, a willingness to articulate initially unpopular positions which later became orthodox (as with Trump on China), a will to action, and strength abroad.

It’s true that Carter brought to a conclusion Nixon’s rapprochement with Beijing, leading to formal diplomatic relations between China and the US. This was entirely sensible. Any president would have done it. But it was realpolitik that undercut the entire idea of Carter running a human rights foreign policy.

Reagan’s human rights critique of Moscow was far more powerful than Carter’s. Crucially, it was aligned with a massive build-up of hard power through Reagan’s defence spending increases. This was crucial in the Soviet Union’s ultimate crisis of confidence which led to its political collapse. Against Carter, the Soviets were confident.

In domestic policy, Carter was also poor. He couldn’t manage relations with congress, his administration was often incoherent.

Inflation, unemployment and interest rates exploded under Carter. He looked pained, ineffective and bereft. He famously held a domestic summit, then made a speech identifying the “crisis of confidence” in America.

This was the “malaise” speech and Americans thought it woeful.

There was often something a bit weird about the way Carter spoke, telling Playboy magazine for example that he “lusted after many women in my heart”.

The American people didn’t lust after him.

After he left office, Carter devoted himself to good works. Even here his geo-strategic judgment was often poor. In 1994, in the middle of a crisis between Washington and North Korea, Carter, against the wishes of then president Bill Clinton, went to Pyongyang, met the North Korean dictator, and fatuously claimed to have “solved” the nuclear problem.

Clinton was furious. Carter’s intervention served no purpose except to make it impossible for Clinton to press the moment. It was probably the last chance Washington had to prevent North Korea becoming a nuclear military power. Today, North Korea has 60 or more nuclear weapons.

Jimmy Carter was an honourable and good man. We should revere him as such. He was also a very, very poor president.

More Coverage

Jimmy Carter was a good man but a bad president.