For 100 years, Jimmy Carter’s life was lived in service towards others

With my wife Nicky, we visited Carter’s boyhood farm and home, the Carter family store, Plains High School, his presidential campaign headquarters at the Plains Depot, brother Billy Carter’s service station and church where he taught Sunday school. We lunched at the local restaurant, talked to shop owners and stood in front of the Smiling Peanut for a photo.

These places offered a window into the former president’s personality and character, helped to understand his deep commitment to human rights, freedom and liberty, and his humility and civility towards others. Carter returned to Plains after his presidency (1977-81) and lived in a modest home with Rosalynn on Woodland Drive.

In August 2015, I interviewed Carter. We spoke at length about his book, A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety (Simon & Schuster). In this and other books, he wrote candidly about his time in and out of politics, his commitment to peace and human rights, his religious devotion, and love of Rosalynn and their family.

He never lost faith. “I’m a religious person and I believe that potentially we will see the finest aspects of humanity forthcoming,” Carter told me. He admired fellow Democrat Harry Truman because of his “humility and his honesty and his political courage”. Carter said meetings of ex-presidents were always “harmonious” but he most enjoyed the company of Republicans George HW Bush and Gerald Ford.

He advocated for careers in public service. “When young people do consult with me, or I meet with a political science class or history class, I encourage them to take whatever talent or ability they may have been given and to utilise that talent and ability to the best interests of themselves and other people,” he explained. “That quite often does involve a political life.”

Because Carter lost re-election in 1980 and only served a single term as president, he has been overshadowed by other post-war presidents. There is no denying that when voters cast their judgment after four years, they opted for a new administration. It is telling that two other presidents who lost re-election, Ford and Bush, were also admired for their dignity and grace.

Yet the Carter presidency is being favourably reassessed by historians. It was a restorative presidency after the disgraced administration of Richard Nixon. Carter placed a premium on personal integrity and public transparency. He faced a number of difficulties not of his own making such as sluggish economic growth, high inflation and an energy crisis. The Iranian hostage saga destroyed his re-election hopes. He left an important legacy on the international stage and helped make the world a better place with the Panama Canal treaties, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) with the Soviet Union and broking the historic peace agreement between Israel and Egypt in 1978 that has been kept by both countries.

When Carter invited Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat to Camp David, there was little prospect of securing a new peace accord. After 13 days of talks, negotiations broke down. Carter decided to make one more attempt before they left. He signed photographs of the three leaders for Begin’s grandchildren “with love”.

Carter explained what happened next: “I gave him the photographs,” he recalled, “(and) he turned away to examine them, and then began to read the names aloud, one by one. He had a choked voice, and tears were running down his cheeks. I was also emotional, and he asked me to have a seat. After a few minutes, we agreed to try once more, and after some intense discussions we were successful.” It was a masterclass in negotiation and deal-making.

The 39th president was intelligent, disciplined and hardworking, and steered his presidency by a moral compass, but lacked some of the elemental aspects of what makes a successful presidency. He was prone to micromanagement, could be dismissive of other views and sometimes insecure. As a Washington outsider, he had a difficult relationship with the media and struggled to find compromise with congress.

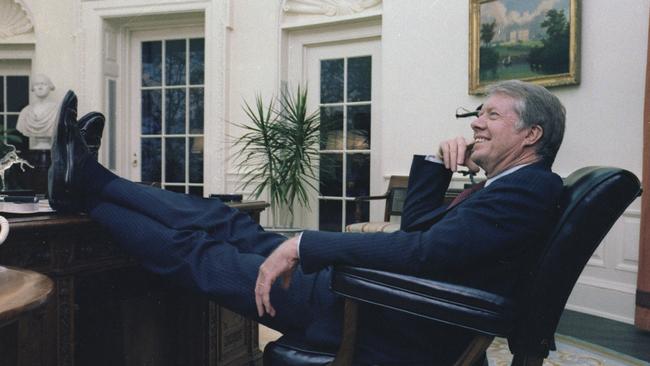

But what stands out is the integrity that Carter restored to the Oval Office, the moral leadership he provided at home and abroad, and a steadfast commitment to leading an honest and accountable government. The combination of courage and humility is rare in politics, yet Carter demonstrated both.

These values continued beyond the White House. His post-presidency work through The Carter Centre included national and international outreach programs overseeing democratic elections, resolving conflicts and hostage negotiations, helping the sick by eradicating diseases, such as guinea worm, and building homes for the poor.

He reinvented the post-presidency. While other presidents have done good works post-politics, notably Herbert Hoover, no former president has done so much for their country or the world in the modern era. This work earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. “My time since the White House has been best for me,” Carter reflected.

Public service began long before politics. He studied at the US Naval Academy, trained as an engineer and submariner, and deployed with the Pacific and Atlantic fleets in the 1940s and ’50s. He worked on the family peanut farm and was a successful businessman. He served in the Georgia Senate (1963-67) and was governor of Georgia (1971-75). He won the presidency narrowly against Ford in 1976 and lost narrowly to Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Carter’s presidential library, incorporated into The Carter Centere, chronicles his life with characteristic modesty. It tells the story of his full life, not just the governorship and presidency. There are campaign buttons, flyers and posters, and a replica Oval Office. On display is his Nobel Peace Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom (1999) and Grammy Award (2006) for an audiobook.

He told me he had fond memories of visiting Australia and participating in military exercises. In his boyhood bedroom in Plains, he kept souvenirs sent by Uncle Tom Gordy, who visited Australia during World War II with the navy. When you walk through the home – which you can do unguided – you can see where those keepsakes were kept on his chest of drawers.

When Carter announced he was running for president in late 1974, a newspaper in his home state headlined its front page: “Jimmy Who Is Running for What!?” The man from Plains was taking on the political establishment. His sunny personality, moral leadership and promise of a new style of government struck a chord. It is hard to imagine today. He agreed. “It wouldn’t be possible because, unfortunately, the American political system has been turned over to the influence of money,” Carter told me. “This would not permit me to have even been a contender. You can’t expect to get into the presidential campaign without being able to raise several hundred million dollars, and I could not have done that.”

In October 2022, I visited the small rural town of Plains, Georgia, home to Jimmy Carter for more than a century. It was a place I wanted to see with my own eyes because, having read Carter’s many books and interviewed him, I knew it had a defining influence on his long life of public service. It was where he was born, and where he died on Monday at age 100.