From #metoo to Mabo and Bluey with a dash of Denuto: recipe for modern Australia

Trust? The less said the better. These moments, movements and ideas have defined us since 1964: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to Bluey, for better or worse.

Over the past 60 years, civilisation-shaping isms – capitalism, communism, totalitarianism, imperialism, tribalism and environmentalism – as well as ideals such as liberty, fairness and equality have been remarkably resilient. Six decades is certainly long enough for new thoughts to arrive, and old ones to die gracefully. Ideas bubble up and blend into one another. Yet just when you thought some things were on the way out, such as industry protection, Anzac, larrikinism and antisemitism, for good and ill, they find a way of adapting to the conditions. Here are 60 ideas, beliefs, forces and innovations to consider. They seep into our consciousness and bend the way we know the world, forming what Germans call the zeitgeist and local theorists have come to know as “the vibe”, thanks to the nation’s most quoted litigator, The Castle’s Dennis Denuto.

1. DNA

The publication of The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (1968) by James Watson changed our understanding of molecular biology. Years earlier, Watson had shared a Nobel prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins (with the foundational work of X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin shamefully not recognised). Later, one of modern science’s greatest collaborations was the Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, mapping the base pairs that make up our DNA. From genetic testing for disease, to ancestry, crime scene investigation and corporate marketing boasts about mission and values, it’s the first and last fragment of humanity.

2. AI

Artificial intelligence is going to be a big star. It’s already so ubiquitous it goes by its initials alone. Its algorithms rely on machine learning, fed by big data sets and the accumulated creativity and wisdom of the past via so-called large language models. Sundar Pichai, the boss of Alphabet, which is boss of Chrome, YouTube and Google (unfathomable, Dr Google has a boss?), reckons AI is going to be bigger than fire, electricity and the internet. At heart, it’s a digital tool that can feasibly replace (or liberate from toil) millions of workers; it will boost productivity and give us all a lot more leisure time. Wait till AI forms an alliance with quantum computing. Yet if we don’t put limits on it, there are fears AI will eat our lunch – and then us, as physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking warned a decade ago.

3. The Internet

One of the reasons technological evangelists think the AI revolution will happen in a relative heartbeat is the plumbing is already in place: the World Wide Web. The “information superhighway” was how we once described the planet’s network of computers that is the foundation of global commerce and, naturally, an arena for criminals to steal data and malevolent actors to launch cyber attacks. For some, the internet is the essence of connection, if not existence. If he were doom-scrolling or shopping online today, would Descartes theorise, “I click, therefore I am”?

4. Misinformation

But the French philosopher would be pressed to discern the union of mind and body in this era of deepfakes. Seeing is not believing and the “eyes” definitely do not have it. Our collective yearning to know has taken a turn to the dark side, where manipulation by demagogues and crooks meets limitless creativity. Fake news is now so pervasive, enabled by the wizards of tech, that we stop believing in anything that doesn’t conform to our existing beliefs. Remember your first love? This could be the moment to return to “old media”, the news you can trust.

5. 9/11

The signal news event of the past six decades was the terrorist attack by militant Islamists on American soil on September 11, 2001. The assault, which levelled New York’s Twin Towers, spawned the US-led global war on terrorism and the hunt for the Taliban, al-Qa’ida and weapons of mass destruction. Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq consumed American prestige and treasure, obliterating countless lives among combatants and innocents. Some see the lasting effects of the war on terrorism – its scale, sheer cost and impact on foreign affairs – as akin to the 40-year impact of the Cold War. Others argue 9/11’s direct legacies include increased militarisation, encroachment of homeland security services into daily life, loss of civil liberties and the rise of the surveillance state.

6. Five Eyes

The seeds of the intelligence alliance, which includes the US, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, were sown during World War II’s clandestine co-operation in the code-breaking industry at Bletchley Park outside London. Its roots deepened during the Cold War, and networks became more sophisticated during the War on Terror and to contain the rise of China’s spying activities over the past two decades. It’s the Anglosphere’s most exclusive, secretive and controversial club, earning Sino ire for its strong support of Hong Kong’s democracy activists and banning Huawei from telecommunications networks.

7. Soft power

Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye developed the theory of soft power. Beyond using military might, he argued in a seminal 1990 Foreign Affairs essay, the US could use soft power – its political values, cultural production and foreign policy – to get other countries to do what it wants and cement its world leadership. Australia, too, embraced this approach in our region. The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper argued we, too, could become influencers by projecting enduring strengths such as our “democracy, multicultural society, strong economy, attractive lifestyle and world-class institutions”. The New Colombo Plan, where young Australians study and take internships in the Indo-Pacific, was Canberra’s signature move.

8. Border security

The world is forever awash with people fleeing war, persecution and poverty. In the late ’70s, Malcolm Fraser opened the door to thousands of Vietnamese “boat people” who would become among the nation’s most successful migrant groups. Over the next two decades asylum seekers would take huge risks at sea, arriving “illegally” in distant outposts of Australian territory. But in 2001, when a freighter called Tampa picked up 438 people from a wooden boat in distress in the Indian Ocean, John Howard seized the moment. “Tampa was the apogee of a change in policy,” he told author Phillipa McGuinness of the birth of the Pacific Solution to send people to Manus Island and Nauru.

9. Anxiety

We used to worry about the bomb and existential threats in the age of terror, but now anxiety has come home to stay. It insinuates itself through the devices we hold in our hands – or, really, that hold our attention in their pervasive grip. In The Anxious Generation (2024), social psychologist Jonathan Haidt traces an epidemic of teen mental illness to the onset of phone-based childhoods in the 2010s after the decline of play-based childhood in the 1980s. Anxiety, depression, self-harm, eating disorders and deaths of despair are on a rapid rise in the worried West.

10. Contagion

The spread of harmful ideas is as rife as the spread of a virus, which can infect humans and machines. Everything is now connected in the world of finance. We’ve lived through a series of crises, such as the 1987 Black Monday stockmarket crash and the series of infarctions in 2008 we call the Global Financial Crisis. Bird flu is at large and the Covid-19 pandemic rewired the planet. Psychiatrists are warning of the rise in cases of gender dysphoria in young people as an example of social contagion.

11. Cancel culture

Can I say that? Was that a micro aggression gone macro? Too late, you’ve just been cancelled. Do not pass go, and watch your pronouns. Sorry, not sorry. Talk to Elon Musk about it.

12. Deglobalisation

The world got smaller and production became cheaper due to free trade – the engine of prosperity for decades, if not a couple of centuries, and the liberator from poverty for billions of people. Now globalisation is prefixed with a “de”. Countries are bringing manufacturing home. Intervention is back and governments are taking control of the economic levers – from price freezes to cash handouts, industry subsidies to curbs on foreign investment. Lower growth and higher prices are just the beginning of this disintegration of the postwar order, where great power competition risks casting the world into rival trading blocs. Massive subsidies are on offer, allegedly to usher in the transition to clean energy.

13. Net Zero

Most of the world has signed up for decarbonisation, with a target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (China has pledged to do so by 2060) to keep the global rise in temperature to below 2C. This transition comes with a heavy cost, which means it’s ripe for rentseekers and shysters. Plus, as scientist and author Vaclav Smil explained in How the World Really Works (2022), our civilisation is so deeply reliant on fossil fuels – to produce the four modern material pillars of cement, steel, plastics and ammonia – “that the next transition will take much longer than most people think”. Net zero doesn’t mean absolute zero or that no carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere. That would be a fantasy. Rather, through some combination of planting trees and technologies that bury emissions produced from industry, transport and electricity generation, the net impact from man-made sources is zero.

14. Non-binary

Binary notation involves a system of ones and zeroes. In computing, for instance, 1 is true or “on” and 0 is false or “off”. What has sustained the digital revolution, however, has not been sufficient to contain our social evolution, namely gender identities of male and female, man and woman, boy and girl. A non-binary person identifies as neither male nor female; their pronouns are they/them/their. Most people identify as being of the sex of their birth, or “cisgender”, while someone who doesn’t is “transgender”. This notion of sex “assigned at birth” is a modern battle line. The number of school students identifying as neither male nor female is now 20 times higher than before the pandemic.

15. Authenticity

American comedian George Burns said the key to success is sincerity: “If you can fake that you’ve got it made.” When politics and culture get hold of originality and fidelity, you end up with today’s zeal for authenticity. You may not warm to a political leader, but you’ll respect them for their public persona if it’s in line with their personal life. Being genuine is hot, but being seen as being true to yourself is hotter. Nothing beats living your best life, except maybe posting about it endlessly on Instagram: the curated life is the only one worth living.

16. Bucket list

Life is finite, even as medical ingenuity and better diets keep pushing out the frontiers of longevity. According to last year’s Intergenerational Report, over the coming 40 years life expectancy at birth is projected to rise to 87 years for men and almost 90 for women. What to do with all those extra years of retirement, let alone the goofing-off time during prime working years due to robotics and AI? You’ll need a retirement plan if you’re going to hike to Everest’s base camp, walk the Camino de Santiago and cut deeply into the kids’ inheritance.

17. Intergenerational equity

As baby boomers (born 1946 to 1964) kick the bucket, we’ll see the greatest transfer of wealth known to humanity. Worldwide, boomers will bequeath $100 trillion in assets to their heirs by mid-century. In Australia, around $3.5 trillion will be transferred over 20 years. The boomers’ great accumulation comes courtesy of the postwar boom, compulsory superannuation and home ownership. As former Reserve Bank governor Ian Macfarlane has explained, “the story of inequality of wealth in Australia is the story of incredible growth in property prices that has benefited older Australians at the expense of younger Australians”. They say you can’t take it with you, but that doesn’t mean one day the government won’t take a slice for itself.

18. Economic rationalism

Tax cuts for the wealthy and big business became known as “trickle down”, “supply-side” and even “voodoo” economics. The surnames of US president Ronald Reagan and Britain’s prime minister Margaret Thatcher became prefixes to the neo-liberal economics orthodoxy that took root in the 1980s. In Australia, it led to deregulation of financial markets, privatisation of public assets, removal of tariffs and decentralisation of wage fixing, the hallmarks of what we know as “the reform era”. Known here as “economic rationalism”, the free-market and fiscal strictures imposed on developing countries called the “Washington consensus” have been in retreat for two decades.

19. The End of History

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 led to upheavals in the communist bloc, most spectacularly to the fall of the Soviet Union two years later. But even before the fall of the wall, Francis Fukuyama called it: liberal democracy had triumphed. In the northern summer of 1989, the fo-po analyst published The End of History in the realist Washington journal National Interest, founded by Owen Harries. In The End of History and the Last Man (1992), the American political scientist claimed we had reached “the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government”. Not so fast, argued Samuel Huntington in The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of the World Order (1996), who saw religious and cultural identities as the coming main arena for hot conflicts (see 9/11, but don’t discount China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin).

20. Identity

More recently, Fukuyama spied another “master concept” to encompass today’s resentments: the demand for recognition, from Black Lives Matter to Brexit. The rise of identity politics is rooted in this dissatisfaction and can’t be fixed through the usual economic means. Today’s politics are sliced and diced along the lines of nation, religion, sect, race, ethnicity or gender, which Fukuyama argues produces an upsurge in anti-immigrant populism, politicised Islam, roiling campuses, and the emergence of white nationalism. At the busy crossroads of a person’s identity is intersectionality, exposing them to a car crash of discrimination and marginalisation. Before crossing the street, check your privilege, white boys and girls.

21. Woke

Things go better with woke. Well, that’s what some kids say, anyway. Once upon a time, people did not realise how bad things were: xenophobia, racism, misogyny and homophobia were at large. Folks were not exactly “chill”, but rather asleep. And then, around 2010, there was a Great Awokening in the discourse; people joined the dots and victims worked out who was oppressing them. The truth spread on campuses and viral channels of opinion, but then came the dead bat backlash. Like its earlier variant known as political correctness, just about anything you don’t like about progressives – such as corporate social responsibility – is because it is woke.

22. POPULISM

We’ve seen this movie again and again: tough guy, hates the elites, understands your outrage, speaks your language, “one of us” (but better). Donald J Trump is the showrunner for the populist, potent and disruptive franchise. Its foundation is likely economic underperformance and social dislocation at a time of rapid change, although some see its roots in identity politics. Political historian Paul Kelly believes Australians still seem resistant to populism, with its appeal limited to the Hansonist fringes, but it remains on the rise elsewhere because governments can’t adequately solve the myriad challenges they face.

23. The Lucky Country

In the year this newspaper was born, Donald Horne published The Lucky Country, a foundational text in our culture; its title used and abused by politicians, academics and marketers ever since. Here’s Horne’s thesis in a nutshell: “Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck.” It was a pungent treatise against complacency by a once radical editor and activist, rather than a celebratory statement of our good fortune to inhabit a mineral-rich continent on the edge of a region that would soon see hundreds of millions of people lifted out of poverty.

24. Consensus

For a time, after Bob Hawke won power in 1983, the nation achieved tripartite alignment: government, business, unions in splendid agreement. OK, that might be exaggerating the amity. But through summits and consultation, the Silver Bodgie manufactured political cover for the disruption he foisted on the nation’s way of earning a crust. Underpinning it all was an Accord with the union movement, a remarkably versatile instrument that went through several iterations to deliver a social wage in return for organised labour’s complicity in keeping a lid on inflation.

25. Banana Republic

In a radio interview with OG shock jock John Laws on May 14, 1986 about a blowout in Australia’s current account deficit, then treasurer Paul Keating warned the nation we were living beyond our means. “If this government cannot get the adjustment, get manufacturing going again, and keep moderate wage outcomes and a sensible economic policy, then Australia is basically done for,” Keating said. “We will just end up being a third-rate economy … a banana republic.” It was a bolt from the blue; voters were “shocked and bewildered” by this inadvertent remark that Paul Kelly said became a “psychological pivot”. “It lifted community consciousness about Australia’s economic predicament to an unprecedented level and it changed the limits of political tolerance,” he wrote in The End of Certainty (1992).

26. Rise of China

Australia did get lucky with China’s admission to the World Trade Organisation in 2001. The superpower’s economic rise has transformed Australia: revitalising frontier states, raising living standards through record-high prices for iron ore, gas and coal, and underwriting the expansion in our education sector. We were barely scuffed by the GFC because of China’s insatiable demand for our exports. But the relationship is hot and cold; nay, more extreme, like fire and ice; China is asserting its hegemony in the Indo-Pacific region, with an unprecedented military build-up, cyber attacks and wolf-warrior diplomacy. Xi changed China and, by necessity, we are changing as well, with Quad and AUKUS the most palpable responses.

27. Cultural Revolution

Like the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square, China’s Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 has been suppressed and forgotten, culminating in a national amnesia. The one to two million estimated death toll from a country turning on itself – families, neighbours, classes, generations scarred by murder and brutality – may be slight compared with the 45 million who perished in the famine from the Great Leap Forward in 1958. But according to author Tania Branigan, it was the apogee of Maoism in its ruthlessness to remake the nation’s soul and for its leader to assert control. “It is impossible to understand China today without understanding the Cultural Revolution,” she writes in Red Memory (2023). “Subtract it and the country makes no sense: it is Britain without its empire, the United States without the Civil War.”

28. Polycrisis

Arab members of the oil exporters’ cartel quadrupled the price of oil in October 1973, leading to a spike in inflation and a deep global recession. Supertramp’s 1975 album cover for Crisis? What Crisis? shows a guy sitting on a deckchair under an umbrella with a distressed city crumbling in the background. We’re now in the realm of what economist and historian Adam Tooze has called the “polycrisis”, a term originally coined by French theorist Edgar Morin in the ’70s. Everything everywhere all at once is going wrong: high inflation and slow growth, wars in Ukraine and Gaza, climate change, pandemic, geostrategic shifts, debt distress, food insecurity, and rising protectionism.

29. Crypto

Do cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, which run on something you’ll never understand called the blockchain, need even more attention than they’ve already had? Units of this virtual money, as real as the air you are holding in your hands, are created through a process called mining. Not by digging dirt like BHP-Billiton or Rio Tinto, but by using computer power to solve mathematical problems. Got it? Crypto uses a lot of electricity; if it doesn’t destroy the planet, it will rob us blind. See the recent case of “Crypto King” fraudster Sam Bankman-Fried.

30. Scandal-gate

In 1974, Republican Richard Milhous Nixon was the first US president to resign from office. He was facing almost certain impeachment from congress for his role in the serial crimes known as Watergate, named after the office complex in Washington that was home to the Democratic Party. But Tricky Dicky’s enduring legacy has been the media’s attachment of the “gate” suffix to every subsequent scandal, no matter how big or small. In America, we had Contragate (arms to Iran) and Troopergate (Bill Clinton’s liaisons), while here we had Wheatgate (wheat for weapons), Utegate (alleged cosy deals for wheels), and Monkeygate and Sandpapergate (Test cricket).

31. Un-Australian

When things turn ugly in life, business or sport, such as the Australian cricket team’s 2018 ball tampering at Newlands in Cape Town, there’s an old saying that “it’s just not cricket”. In the ’90s, self-confessed cricket tragic and tracksuited walker John Howard popularised the term “un-Australian” to denounce his political opponents, including striking workers, Iraq war protesters and the anti-globalisation movement. But the term reached its zenith when Big Meat’s spruiker Sam Kekovich declared in 2006 that not eating lamb was un-Australian.

32. Hydration

OK, just over halfway through, you need a drinks break. Still, sparkling or tap? Sure, we live on the Earth’s driest continent, but when did this mania for buying and carrying bottled water take hold? What a lurk for something that is free! I first noticed people guzzling the stuff after (our) Olivia Newton John’s Physical music video was released in 1981. This idea that you need eight glasses of water a day – a couple of litres – is a scam run by Big Health, the Anti-Sugar lobby and the brewing cartel that wants to squeeze the water supply to craft beer minnows who are trying to stay independent.

33. The Pub Test

If you’re not sure which way the wind is blowing on an issue, there’s always the pub test, the last bastion of our home-grown democracy, the laser-beam of focus groupthink. There’s the sniff test in the fish shop, but this examination can be as searching as an ICAC counsel assisting, more final than a royal commission. For a politician, failing the pub test can be worse, a lot worse, than failing a breathalyser or getting done over by Reds Kezza and Leigh or Sarah from “7.30 Report land”. Depending on your slant, it’s either a short hop, step or jump to being on the “wrong side of history” or pre-selection for the Greens.

34. Doping

East German athletes, Chinese swimmers, Lance Armstrong and allegedly the entire peloton on Le Tour, Ben Johnson, Marion Jones and the whole damn Russian Federation on the juice. Who cares, right? But doping got real in 2003 when Shane Warne was banned from cricket for a year after taking a banned diuretic (which can mask steroid use) given to the GOAT by his mum. Warnie said cricket authorities had bowed to “anti-doping hysteria”. No mums were involved but there were dopes and dupes aplenty as the Essendon Football Club’s supplements program and other mischiefs presaged what one official called the “blackest day in Australian sport” after the 2013 release of a report by the Australian Crime Commission.

35. Culture Wars

In post-materialist societies, where the needs of food, water, air and shelter are essentially guaranteed for the many, the polity is often mired in ideological contests for supremacy between social groups. This is less like the democratic interplay of the salary cap and draft AFL and NRL, say, and often more like the deep tribal enmities of the Balkans (Disclosure: so I’m told) or the inquisitions to root out heretics back in the day. The local “debate” on colonisation in the ’90s, with “black armbands” and all, known as the history wars, was a foretaste of today’s skirmishes over Welcomes to Country and Australia Day. For Indigenous Australians, and a growing number of sympathisers, January 26 1788 is “invasion day” and sovereignty was never ceded.

36. Mabo

In June 1992, the High Court recognised the claim that a group led by Eddie Koiki Mabo held traditional ownership of land on Mer (Murray Island) in the Torres Strait. The doctrine of terra nullius – that is, land belonging to no one – was overturned and the following year the Native Title Act was passed, paving the way for Indigenous Australians to make land claims in cases where they can establish continuous connection to the land. Where there is a conflict between a native title claim and the Crown, the judgment said the Crown would prevail.

37. Stolen Generations

In April 1997, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission published Bringing Them Home, a landmark report detailing the findings of its inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. One of the key recommendations was acknowledgment and a formal apology to the Stolen Generations. In 2000, a quarter of a million people walked across the Sydney Harbour Bridge in support of reconciliation. Conservative leaders stayed home, eschewing what they saw as empty symbolism; practical measures to “close the gap” and tough love like the NT Intervention were needed.

38. Reconciliation

In 2008, Kevin Rudd delivered a formal apology from the Australian parliament to those forcibly removed from their families over generations. That February morning was a rare moment of national healing. The metaphorical slow train of reconciliation gathered momentum at Uluru in 2017. Invoking the spirit of the 1967 referendum which altered the “race power” and allowed for Indigenous people to be counted in the census, the convention sought a constitutional change, including a First Nations voice. “We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future,” the Uluru Statement From the Heart said. Anthony Albanese’s proposal to recognise First Nations people and establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice to parliament and executive government was overwhelmingly rejected at the October 2023 referendum, with a majority Yes vote recorded only in the ACT.

39. Republicanism

Changing the Constitution via a referendum requires a rare alignment of politics, culture and the aforementioned vibe. Since Federation, only eight of 45 proposals have been carried. In 1999, after a constitutional convention the previous year, there was a proposal to establish the Commonwealth of Australia as a republic “with the monarch and governor-general being replaced by a president appointed by a two-thirds majority of the members of the commonwealth parliament”. The model put forward by John Howard split republicans; the referendum failed, with 55 per cent of the nation voting No and only the ACT registering majority support for the Yes case.

40. Marriage equality

Less controversial was the 2017 proposal to reform the Marriage Act to allow same-sex couples to tie the knot. The change of attitude in our suburbs and towns – via family experience, Mardi Gras, Pride rounds, the ubiquity of LGBTQIA+ creatives – had moved more quickly than the previous national leaders, Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott, who were not for turning: marriage was between a man and a woman. Australians shrugged; if you want to get hitched, just do it. Almost 80 per cent of eligible voters participated in the postal survey, with the Yes vote garnering 61.6 per cent support.

41. Inclusion

Perhaps the biggest change in the life of the nation these past six decades has been the greater freedom to be who you want to be, although for many the struggle for inclusion feels never-ending. According to the federal Attorney-General’s Department, “it is unlawful to discriminate on the basis of a number of protected attributes including age, disability, race, sex, intersex status, gender identity and sexual orientation in certain areas of public life, including education and employment”.

42. Misogyny

What at first seemed to be a routine rejoinder by Gillard to a parliamentary motion, put forward by then opposition leader Abbott about the conduct of a controversial house Speaker, exploded within seconds. “I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man,” she declared in October 2012. “I will not. And the government will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man. Not now, not ever.” Writing on the 10th anniversary of the “misogyny speech”, University of Melbourne academic Julia Bowes said it “vaulted Gillard into the stratosphere of global viral content, inspiring hundreds of thousands of women and girls around the world”.

43. #MeToo

Bowes went on to reflect on the murky historical context of the moment and argued “there is no need to put the former PM on a pedestal”. Nevertheless, a decade on, there was “still a feel-good story here” about how societal attitudes had changed, supercharged by the #MeToo movement, which highlighted tolerance of workplace sexual harassment and active cover-ups of sexual assault. “The global movement to call out harassment and expose abuses of power has created unprecedented space for survivors to come forward and seek justice,” Bowes wrote, ahead of the traumas and political-media-legal quagmire of Australia’s most prominent case. In a defamation trial, political staffer Brittany Higgins was found “on the balance of probabilities” to have been raped by Bruce Lehrmann.

44. Gender pay gap

Since 1969, after a long campaign, industrial action and decisions by the pay umpire, it’s been against the law to pay women less than men for performing the same role or different work but of equal or comparable value. Gender pay gaps are not a measure of equal pay but rather, as the Workplace Gender Equality Agency says, “the difference between the average or median pay of women and men across organisations, industries and the workforce as a whole”. There are two official data sets, with the WGEA’s estimate of a 21.7 per cent gap from data provided by private employers with more than 100 staff, while an ABS survey of average weekly earnings shows the gap is 12 per cent.

45. Diversity

Drilling into the causes of the gender pay gap finds cultural change is required to remove the barriers for female participation at work. But over the course of 60 years, and widening the lens, we’re in a golden age for diversity. Companies are committed to broadening the talent pool because it leads to better decision-making, with more women now on boards and in leadership positions. Even parliaments are changing, reflecting Labor’s Emily’s List quotas and more independent and minor party representatives as the major party cartel disintegrates. What used to be called affirmative action is now the new corporate doctrine under the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion banner.

46. Multiculturalism

The post-pandemic influx of foreign students, backpackers and temporary workers has led to the biggest ever single-year growth in our population. Over 30 per cent of our population are migrants, while a majority of Australians have at least one overseas-born parent. Multiculturalism, designed to be a two-way deal of rights and responsibilities, gained traction in the ’70s, and has evolved under successive waves of immigration; the concept is frequently tested, often in response to conflicts far from our shores and the mischief of authoritarians.

47. Masterchef Rules

The mash of migration, entertainment, world travel and fresh produce on demand all year round has spawned a gastronomic revolution. Our palates are broader and cooking has become performative; we “plate up” rather than serve food. Restaurateurs are not mere business owners, they’re “celebrity chefs” striving for “hats”, our homegrown equivalent of Michelin stars. Contested cooking on prime time television has fed the revolution.

48. Reality TV

Other than live sport on free-to-air, such as State of Origin rugby league or the AFL grand final, reality TV may be the last vestige of so-called “appointment TV”, where people tune in at the time of the live broadcast. There are imports, of course, but the highest ratings are for local content. Big Brother, Australian Idol, Australia’s Got Talent, Lego Masters, I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here, The Block, Grand Designs, MasterChef, My Kitchen Rules, Ready Steady Cook, Survivor, Alone, Married at First Sight, The Bachelor, The Bachelorette, The Farmer Wants a Wife, The Amazing Race, Love Island, Bondi Rescue, Bondi Vet, Gogglebox, Border Security, The Real Housewives, Dancing With The Stars, The Voice.

49. Streaming

Digital killed the terrestrial broadcast star, as VHS, DVD and BlueRay box sets fell by the wayside. From Netflix to Binge, Stan, Apple TV and Spotify, content-on-demand rules. Consumers are curating their own experiences depending on schedules and appetites. Quality, long-form television has also changed the movie business, but Hollywood fights back through franchises like The Avengers in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and blockbusters such as Top Gun: Maverick and Barbie.

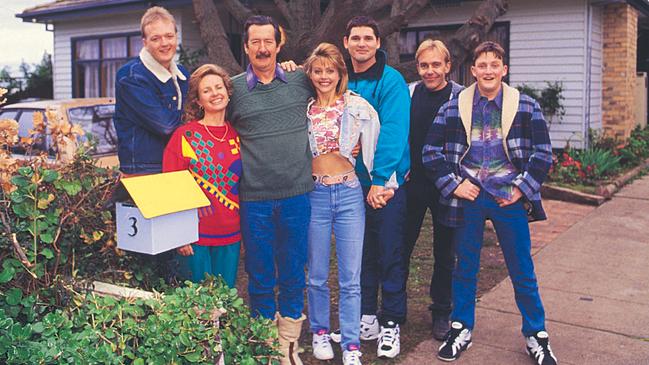

50. Generation Bluey

Australian preschoolers rompered in the ’70s, wiggled and pyjam-ed into the new century, then giggled and hooted all the way to 2018 when Bluey hit big and little screens on ABC Kids. The animated story of Bluey, a blue heeler puppy, and her sister Bingo, mother Chilli and father Bandit, is the feelgood family adventure of our time, providing the modern life lessons in kindness, tolerance, humility and fun.

51. Helicopter Parents

Away from Bluey, the world looms as a dangerous place. If kids in the ’60s and ’70s were free-range, roaming suburbs on bikes till dusk, their own children were kept busy with “activities” and managed by “helicopter parents”. Maybe not as tightly as the offspring of Yale professor Amy Chua, author of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, who were subjected to strict discipline and music lessons. Coddling kids in this way led to anxiety and depression, with many lacking resilience, such as an inability to accept criticism. Sorry, not you, snowflake.

52. Punk

Queen Elizabeth was no snowflake. If she was annoyed by God Save the Queen from the 1977 album Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, she never showed it, although her surrogates at the BBC and Fleet Street lost their minds. The Punk aesthetic exploded in Western fashion, art and music – an in-your-face expression of rebellion, alienation and anger, launching a million amateur bands in homage and defiance, through post-punk, new wave, grunge and alt-everything. In Brisbane, The Saints released (I’m) Stranded, catching the punk wave months before Johnny Rotten snarled “I am an Antichrist”.

53. Pentecostalism

Never mind the Sex Pistols, for there was a fast-growing Pro-Christ movement in the US and Australia. Pentecostal Christians, or “happy clappies” as they were often mockingly described, were among the fastest-growing religious groups over recent decades. Hillsong Church was established in Sydney’s suburbia in 1983 by Brian and Bobbie Houston and its congregations have sprouted in 20 other countries. While many Christian denominations were in decline, the theologically and socially conservative prosperity gospel movement thrived.

54. Canberra Bubble

Scott Morrison was the first and only pentecostal Christian to become a head of government, anywhere in the world. Even though ScoMo was a creature of party politics, he derided the nation’s insiders and the isolation of the bush capital when he spoke of the “Canberra bubble”. It was an echo of Donald Trump’s rhetorical assault on DC, or “the Swamp”, which he vowed to clean out when he became US president in 2017. Behind this facade of democracy, according to US right-wing conspiracy theorists, is the deep state, a clandestine network of intelligence agents, officials and money movers, corrupted by power.

55. Trust

Trust me, I’m a judge (tick). Trust me, I’m a doctor (OK). Trust me, I’m from the government (hmmm). Trust me, I’m a journalist (stop laughing, this is serious).

56. Working Families

Elites in organised labour, academia and corporate Australia were, naturally, always out of touch with working families; they’d been the enemy of “hard-working Australians”, and earlier had rigged the game against the aspirationals. In the ’90s they were termed “Howard’s battlers”, the outer-suburban voters from Labor’s traditional heartland, cashed-up bogans who were rejecting envy and class war for lower taxes and free enterprise. They were often fly-in, fly-out mining workers, or the tribe of tradies behind the Big Build in our cities; in the suburbs they quote whatever they think the market will bear for a new deck. Tell ’em he’s dreamin’.

57. The Castle

The Castle (1997) is a satire about our property-obsessed nation. The Kerrigan family is facing an almighty struggle to hold on to their “home”, not house, which is earmarked for compulsory acquisition because of the expansion of the adjacent airport. Lines have echoed down the years (“It’s the vibe of it. It’s the Constitution. It’s Mabo. It’s justice. It’s the law”; “This is going straight to the pool room.”) Written and shot at breakneck speed, it has a do-it-yourself aesthetic in an era of Hollywood bloat. Some alleged the film was punching-down on battlers by middle class upstarts of the over-achieving Working Dog collective. But they’re wrong. It’s a comedic treasure. Like Denuto, I rest my case.

58. Anzac

In Sacred Places (1998), Ken Inglis observed war memorials were the shrines of a “civil religion”, the cult of Anzac. In 1965, the historian had written The Anzac Tradition, an essay that put the subject on a new plane; as one colleague said, it was simultaneously critical and respectful, yet attentive to “the deep currents of pride, loss and suffering that subsisted, almost unexamined, in Australian culture”. That year, Inglis had been part of a pilgrimage to Gallipoli with 300 others, some of whom under a full moon had steamed from Lemnos to Anzac Cove on the night of 24-25 April, 1915. Anzac inspired vernacular greats Les Murray and Les Carlyon, as well as director Peter Weir, who regarded his Gallipoli (1981) as a war memorial in celluloid. The film, and more accessible travel to the peninsula, have inspired younger generations to make their own pilgrimages.

59. Resilience

April 25 is a national day of remembering and honouring service. It brings to tears even hardened football coaches, unable to express in words the weight of the occasion. Along with Kokoda, Anzac summons mateship, courage, sacrifice and resilience – the quality to grind it out in life; if not to triumph, to act with vitality and dignity in the struggle. It’s been summoned by leaders during floods and fires, all through the disruptions of the pandemic, and even to build up local industries. Presently, resilience has adapted into mindfulness, the idea we can respond to setbacks with clarity through breathing, quiet and reflection. We don’t just have to put on our “big boy” resilience pants.

60. Australia’s Three Stories

In his address to our 50th anniversary dinner in 2014, Noel Pearson first proposed the concept of the three stories of our nation. “There is our ancient heritage, written in the continent and the original culture painted on its land and seascapes,” he said. “There is our British inheritance, the structures of government and society transported from the United Kingdom fixing its foundations in the ancient soil. There is our multicultural achievement: a triumph of immigration that brought together the gifts of peoples and cultures from all over the globe – forming one indissoluble commonwealth.” Pearson declared we stood on the cusp of bringing these three parts of our national story together with constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians. Reconciliation is an unfinished project. Just like our island home, it’s a magnificent idea.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout