Southern Cryonics ready to welcome first Australian clients for cryonic freezing

It’s here. Australia’s first cryonics facility is ready to take its clients into the deep freeze but what kind of world could they wake up to?

This is a story about life and death. It’s a story about life after death – not in a heavenly, sitting-on-a-cloud-strumming-a-harp sense, but a physical resurrection: a Lazarus job, no less. Our story begins in the unlikely setting of a cafe at the Westfield shopping centre in Sydney’s Bondi Junction. Peter Tsolakides, a retired oil company executive from nearby Dover Heights, takes a sip of his coffee and gazes out the window at the bag-laden shoppers passing by as he contemplates a question: what does he expect will greet him when, in about 250 years’ time, if all goes well, his cadaver is removed from storage in liquid nitrogen at minus 196C, thawed out, and jolted back to life?

It’s not just a philosophical question for Tsolakides, but a practical one: he is the driving force behind the first cryonics facility in the southern hemisphere, at Holbrook in southern NSW. It’s been a long haul – a dozen years in the planning and building, beset lately by Covid supply-chain issues – but now, finally, the Southern Cryonics facility is complete. The sophisticated cooling chamber from China, which will carefully bring the bodies (or “patients”, as cryonics advocates prefer to call them) down to minus 196C after their natural death, is up and running; the American-built cryostat for storing them is installed. If any of the 47 people in Australia who have signed up for this extraordinary venture were to become mortally ill, a crew of cryonic technicians is on standby to rush to their deathbed. “We’re ready,” says Tsolakides.

The 72-year-old is good company: genial, open, and curious about the world. He has two degrees and can code in all the major computer languages (he’s been programming since the late ’60s, when computers were the size of caravans and you fed them with ticker tape). He has lots of stories about the three decades he spent as a globetrotting executive for ExxonMobil, overseeing the oil giant’s strategic plans in countries including Thailand, Japan and the US. He has close-cropped silver hair, and keeps a comb and a pen in his shirt pocket. His smartphone is very high-end.

So, when Tsolakides is revived in the latter half of the 23rd century (that’s his best guess when it will happen), what sort of second life does he expect? Well, for a start, he won’t necessarily be shackled to the decrepit old body that wore out and gave up in his first life. “The technology will exist to create whole new bodies, if your existing body can’t be repaired,” he says. Science is already making progress on that front, he reasons, in fields such as cloning, tissue regeneration and robotics. “The brain is the really important bit. As long as that can be revived, ‘you’ will be able to come back in any sort of body you want.”

He sees a future in which humans and computers will have converged, and existence plays out in an amalgam of real-world and virtual-world spaces. He’ll be happy with a second life like this. “I’m an optimist,” he says. “I think we’re living right now in the best era that humans have ever lived in, and the advancement of science and medicine means it’ll get better still.” In this future Tsolakides envisions, people will choose how long they want to live for – immortality will be an option. He can’t imagine ever being bored in a world of limitless possibilities, but maybe, eventually, he’ll have had enough and will call time on his second life. After how long, does he think? “It could be thousands of years, but who knows? I can’t answer that.”

First things first, though. Upon revival, he’ll have a few questions for his fellow citizens of the 23rd century. “Some of the big mysteries of science, which they’ll have an answer to by then,” he says. “Is string theory correct? What is dark matter? What happens inside a black hole? Are there really multiple universes?” Amid the hiss and clatter of the barista’s station, and the hubbub of the Westfield food court drifting up from the floor below, he looks thoughtful for a moment, considering all the wonderful opportunities that await in the next life. “I’m a curious person,” he says simply. “I want to see what the future looks like.”

It was a US academic named Robert Ettinger who kick-started the field of cryonics with his 1962 book The Prospect of Immortality. The theory (perhaps “belief” or “hope” are better words) is that a human body, skilfully cooled to a very low temperature immediately after its natural death, can be preserved in “cryonic suspension” until science has solved the problems of disease, ageing and mortality – and then revived. Tsolakides reckons the technology to achieve this is about 250 years away. He sees the beginnings of it already, in fields such as nanotechnology, gene editing and tissue regeneration – but really, he says, who knows what this far-distant tech might be? We can’t conceive of it now, in 2023, any more than someone on the First Fleet could have wrapped their head around the idea of the metaverse. Others who’ve signed up with Southern Cryonics, as we’ll see, believe the technology to bring people back from the dead will arrive much sooner.

–

“I’m a curious person. I want to see what the future looks like”

–

Cryonics sounds bonkers, on the face of it – and let’s be clear, it is given short shrift by most mainstream scientists and physicians (most, but not all: a digital open letter by scientists supporting it as a legitimate endeavour has attracted 68 signatories in the past 18 years, including figures from NASA and Harvard). Yet the handful of cryonics facilities around the world attests to the allure of a promised second life. As well as the new venture in Australia, there’s the Cryonics Institute in Michigan, USA, with 237 people currently in cryonic suspension (including Ettinger, who died aged 92 in 2011, plus his mother and both of his wives). There’s Alcor in Arizona, with 203 in cryonic suspension, and Oregon Cryonics, a centre specialising in neuropreservation, which is – look away now if you’re squeamish! – the cryonic suspension of the head only. There are other cryonics facilities in Switzerland, China and Russia. Tsolakides estimates there are about 600 people in suspension around the world, including “a few” Australians. “Until now people here have had no choice but to go abroad for it,” he says.

(By the way, that story about Walt Disney being the first person to undergo the procedure? It’s an urban myth. Disney was cremated after his death in 1966, his family insist. The first was in fact James Bedford, a University of California psychology professor, who died in 1967 and is now a “patient” at Alcor.)

Tsolakides’s own interest in the subject was sparked when he read Ettinger’s seminal book while studying chemistry at RMIT in Melbourne in the late ’60s. “It sounded so reasonable to me,” he says, “and I really thought that by the time I was at retirement age I’d be able to go down the road and sign up to a local cryonics facility, you know? I thought they’d be everywhere.” Things didn’t pan out like that, though; when he retired in 2008, and returned from overseas, he looked around and there was nothing. “I realised that if we wanted a facility here in Australia, we’d have to create it ourselves.”

The non-profit Southern Cryonics was brought to fruition by 35 founding members, who each kicked in between $50,000 and $70,000 to get the facility built; a further 12 members have since signed up. They come from all walks of life, Tsolakides says. Their ranks include a doctor, a bus driver and several families. They’re from all over Australia, country and city, “although Perth is over-represented for some reason”, he says. They are mostly secular people, interested in technology and science, and optimistic about the future. And about 80 per cent are men – the same proportion as in other cryonics organisations around the world. Why is that? “I think it’s because women are more interested than men in relationships – they don’t like the idea of coming back and not knowing anyone,” Tsolakides says. Doesn’t that bother him, too? He takes another sip of his coffee and shrugs his shoulders amiably, as if to say, C’est la vie.

There’s no chance of Barbara and Allan Pease coming back alone: they’ve written it into their wills that they want to be revived at Southern Cryonics simultaneously, “and if one of us doesn’t unfreeze properly, the plug gets pulled on the other one,” says Allan. “Neither of us wants to come back if we can’t be together.”

If their names sound familiar, it may be because you have one of their books on your shelves; the couple have written 18 nonfiction bestsellers, including The Definitive Book of Body Language and Why Men Don’t Listen and Women Can’t Read Maps. They live on a 17ha property in the rainforest at Buderim on the Sunshine Coast, and run a portfolio of businesses that includes a TV and music studio, a real estate arm, and public speaking tours that take them all over the world lecturing corporate types on the art of human communication.

“We have a great life,” says Allan Pease, 71, who has agreed to speak on behalf of them both. “We do fun things, we travel, we meet interesting people. Life is fabulous. Why does it have to come to an end?”

It was a matter of life and death that sparked their own interest in cryonics. Pease had been living with advanced prostate cancer for a few years when he and Barbara decided they wanted to start a family. He was in his early fifties at the time, Barbara a decade younger, and they shared four older kids from previous relationships. The couple began IVF, which yielded a clutch of embryos. One of these was used straight away, and became their son Brandon, who’s now 18. Another was cryopreserved – a standard procedure in reproductive medicine – and put in storage. “Three years later, it was thawed out and transferred to Barbara’s womb. And that embryo became our daughter Bella, who’s just turned 15.”

Pease recalls their wonder at the idea of a human embryo, invested with the spark of life, being put “on hold” in liquid nitrogen for three years then coming back. “Amazing,” he says. The couple started looking into cryonics, toured the Alcor facility in Arizona, and signed up with Southern Cryonics when the Aussie venture launched its drive for founding members.

Pease’s cancer has never been in remission. “It has stalked me now for 24 years,” he says. He takes comfort in the idea that when it finally gets him, his death won’t last forever. It won’t even last very long. “I put the time-frame for coming back at between 20 and 50 years,” he says, citing the rapid advances of medicine and technology. “We’ve spoken to the older four kids about this, and they’re comforted by it too. Our 41-year-old daughter is even thinking of signing up.” (Southern Cryonics is open to new people: there’s an annual membership fee of $350, and the $150,000 cost for cryonic suspension – payable after death – is typically covered by a life insurance policy.)

Pease believes the prospect of immortality is just over the horizon; cryonics is a back-up plan, in case his natural lifespan falls short. “I think if you can make it to 2040, you’ll probably have the option of living forever,” he says. It’s an idea championed by the lavishly bearded English gerontologist Aubrey de Grey, who argues in TED Talks that ageing is a disease that will soon be cured; de Grey reckons the first humans who will live to 1000 have already been born. Pease acknowledges it’s a strange idea. “For all of history humans have been born, they’ve lived and they’ve died – so the concept that this is all about to change is pretty hard for people to get their heads around,” he says.

Elphie Coyle, a fresh-faced 39-year-old from Melbourne, is thinking along similar lines. He, too, is a founding member of Southern Cryonics, and a smart, driven entrepreneur, the boss of video game firm Lightmare Studios. Coyle was a Pentecostal youth pastor in his twenties, before his faith eroded “in the absence of empirical evidence about what happens on the other side of life”, he says. Now an agnostic, he subscribes to the thinking of de Grey, and views cryonics as a “short-term solution” in the event that he dies before medical science has cracked the knotty problems of mortality. If Coyle were to be put in cryonic suspension next week, he believes it would be “only 20 to 50 years – 100 at most” before he came back. How confident is he that it will work? “I’d say there’s about a 50 per cent chance of success,” he says. (For the record, Pease puts the figure at 70 per cent; Tsolakides says 10-50 per cent). “But even if it’s more like 0.01 per cent, I’d still take that chance over the alternative – having my body cremated or put in the ground.”

Coyle’s partner Nadine Thomas, 25, has signed up with Southern Cryonics too. “We’ve talked about the possibility of us being revived at different times, and one or neither of us not making it, but we still think that the chance to be reunited and continue our journey together, even in an entirely different world, is worth the risk,” Thomas says. “Cryonics is about embracing the unknown and having faith in the possibilities ahead of us.”

–

“Life is fabulous. Why does it have to come to an end?”

–

Coyle aspires to live for hundreds or thousands of years, but he acknowledges this is contingent on a benign future for the human race. He has some doubts about that. “Technology is advancing at an exponential rate, and it will transform our world in coming years,” he says, citing Artificial Intelligence, nanotechnology and Elon Musk’s Neuralink, which is developing brain-computer interfaces. “The future could be amazing. But these emerging technologies also put power into the hands of individuals who may have malicious intent, and they could stuff it up for everyone. So I think as a society we’re living on a knife-edge right now.”

Holbrook, population 1650, is a pleasant town of wide streets and tidy houses off the Hume Highway, midway between Sydney and Melbourne. It’s a popular stopover for travellers, who can wander around the Holbrook Submarine Museum (a 90m-long decommissioned sub, HMAS Otway, sits in the grounds beside the main street) and the National Museum of Australian Pottery. A casual visitor wouldn’t notice Southern Cryonics’ new warehouse in an industrial park on the edge of town. There’s no sign; the only clue that this isn’t your average storage facility is the 6000-litre liquid nitrogen tank outside.

For now, the facility has just one cryostat – a gleaming, stainless steel vessel, 3.5m tall, that will accommodate four “patients”. It’s a giant vacuum flask, essentially: the same insulating technology that’s used in Thermos bottles. More cryostats will be added as the facility expands in time. The bodies will be stored head-down, a failsafe measure to ensure that in the unlikely event of a leak, the head – the most important bit – would be the last to thaw.

The technique to prepare the body for cryonic suspension kicks into gear immediately after the person’s natural death. First, the body is cooled with ice packs and the blood is replaced with liquid cryoprotectant, a type of antifreeze, to prevent ice crystals forming in cells (which would cause catastrophic cellular damage) during the deep cooling stage. Then the body is chilled to dry ice temperature, minus 79C, at which point it goes into a cryonic “cooling chamber”, where over a day or two it is slowly brought down to minus 196C. The goal is vitrification, where the body ends up in a glass-like state; if you were to hit it with a hammer, it would shatter into hundreds of pieces. The final step is lowering it into the cryostat; once in there, the only maintenance required is an occasional top-up with liquid nitrogen.

The technique, fine-tuned by Alcor and the Cryonics Institute in the US since the late ’60s, takes its cues from a branch of physics called cryogenics, which studies the behaviour of materials at very low temperatures. (You’ll sometimes hear cryonics and cryogenics used interchangeably, but they’re not the same). One important application of cryogenics is the storage of certain types of human cells. “It’s routine now in medicine to cryopreserve stem cells, red blood cells, sperm, eggs and embryos,” says Dr Saffron Bryant from RMIT in Melbourne, who works in this field. The 32-year-old is researching new cryoprotectants and techniques that may one day allow human organs to be stored long-term for transplant. That would be a game-changer for medicine. “It would enable us to have organ banks – which would end transplant waiting lists,” she says.

But science is still “decades away” from this goal, Bryant reckons. One of the difficulties is the physical size of organs; another is their complexity. “A typical organ contains dozens or hundreds of different types of cell,” she explains. “And each cell type requires a different cryoprotectant treatment, or a different cooling method, in order to remain viable.”

Outside of her pioneering research, Bryant is also a prolific author, with 35 sci-fi and fantasy novels to her name. Some of her stories feature cryonic suspension. So what’s her academic take on this subject? “Oh, I need to be careful here,” she says, laughing. And then: “Successfully preserving a human, such that it remained intact at a cellular level, would be much, much harder even than cryopreserving an organ. But never say never.”

To be fair, cryonics advocates reckon a bit of cellular damage is no problem – nanotechnology will be able to fix that up, they say. But when it comes to the final step, restoring consciousness, well, that’s where you bump up against some deep, mysterious questions.

Let’s dip a toe into those mysteries for a minute, shall we? It has probably struck you that cryonics takes a materialist view of life, with its ideathat your character, your memories, your values and beliefs – everything that makes you you – reside in the physical structures of your brain and body. But is that correct? Others would certainly disagree. A Christian might explain it in terms of the soul. A Buddhist monk would chuckle and say your entire notion of a “self” is illusory. And a biologist would say that, actually, all lifeforms are energetic systems through which matter is continuously passing. You are a collection of cells that are constantly in flux, constantly changing. About 98 per cent of all the atoms in your body are replaced every year, according to a famous report by the Smithsonian Institute. So how can that be squared with cryonics’ notion that the essence of “you” resides in matter?

–

He wants to have his mind uploaded into a supercomputer “the size of a shoebox”

–

Let’s put it another way. The human brain is a 1.4kg lump of soft grey matter. The human mind is a function of the 86 billion neurons it contains, of their fantastically complex networking and electrical/chemical firings. It’s fair to say that science has – so far, at least – no idea of how these 86 billion neurons give rise to consciousness.

And yet, and yet. Who’s to say this knowledge can’t be worked out some day, and used to reawaken someone from cryonic suspension? In the year 2023, it feels rash to declare anything impossible as a future that we’d imagined was far off now comes at us in leaps and bounds, from autonomous drone swarms to AI and the metaverse.

The Weekend Australian Magazine took a straw poll of half a dozen top doctors and scientists around the country, emailing them to ask a simple question: Is cryonics feasible? Three responded. Dr Alan Finkel, a neuroscientist who was Australia’s Chief Scientist from 2016 to 2020, answered: “No. Cryonics is resurrecting the dead. It would be much harder than colonising Mars; a little easier than time travel.” But the other two – both eminent cardiologists from the heart and lung transplant unit at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney – framed their answers in a rather different way. “Not in my lifetime and probably not in my grandchildren’s,” wrote Professor Peter Macdonald. His colleague, Professor Christopher Hayward, responded in just two words – but two words laden with a tantalising possibility: “Not yet!”

“What I’m going to say next will probably sound really weird,” says Peter Tsolakides towards the end of our meeting in the Westfield shopping centre cafe. I lean in closer, quietly thrilled at the idea of this conversation taking an even more mind-boggling turn. “My thinking is that ‘mind uploading’ will be possible in about 80 years’ time,” he says.

It’s an idea that has wide currency in futurist circles: if your entire neural architecture could be copied into a computer, it might generate a facsimile of your consciousness – a digital “mind” that expressed your thoughts, felt your feelings, cherished your memories and held your beliefs. But would it be you? “Ahhh,” says Tsolakides, smiling warmly. “Yes, you start to get into philosophical questions like that. It’s a pretty esoteric area. You ought to speak to Phil Rhoades about it.”

Rhoades, from Cowra in NSW, is the facility manager at Holbrook – although cryonic suspension there is his Plan B for the next life. Plan A is to have his mind uploaded, perhaps into a supercomputer “the size of a shoebox”, he says; this would forego the limitations of a biological body, with all its demands for food, water and air, and free Phil 2.0 to undertake interplanetary space travel. Would he be happy with a second life like this? “Oh yes, sure,” he says without hesitation. “As long as that entity still feels like Phil, that’s fine, I don’t care.”

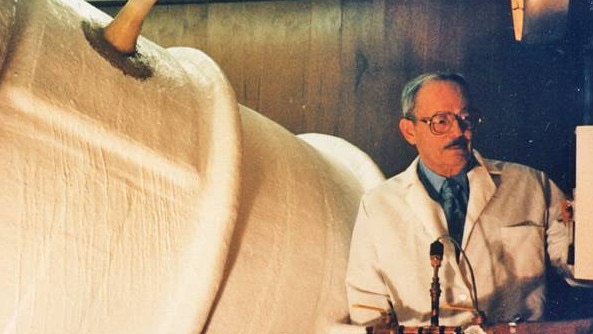

The 71-year-old, who spent his career in biomedicine and IT, reckons mind uploading is only a few decades away. He points to the Human Connectome Project run by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is seeking to produce a comprehensive “network map” of the human brain; this “will help researchers begin to decipher the electrical signals that generate our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours”, the NIH says. A complete network map of the human brain is still years away, though, and time isn’t on Rhoades’s side; he has a genetic predisposition for dementia, the disease that killed his father – hence the need for that Plan B with Southern Cryonics.

As an interesting side project, Rhoades is the custodian of 11 human brains, which have been bequeathed since 2008 to his non-profit Neural Archives Foundation; they’re stored in medical cryogenic facilities around the country. He sees these brains as “historical repositories of unique human lives”, and expects that in coming decades the memories stored in their neural architecture will be accessed, and translated into sounds and images. Maybe, he hopes, it will be possible to restore consciousness to them too. “Imagine these people being able to communicate across many generations, to their great-great grandchildren,” he says. “That’s what I’m thinking may be possible.”

There’s a personal, poignant side to this endeavour: among the brains in the Neural Archives Foundation are those of his own parents, Gerald and Dorothy, who died 10 days apart in 2016, aged 89 and 84 respectively. “I was close to my parents and I’ve never stopped missing them,” Rhoades says softly. “It’s my hope that I will one day be able to talk to them again.” What would he ask them? “Well, they were happy for me to cryopreserve their brains, but Mum did say she thought it would never work. So I guess I would just like to surprise her.”

Southern Cryonics’ life-raft to the future will push off from the shores of the early 21st century as soon as the Holbrook facility takes in its first patient. (“Nobody wants to be the first,” admits Peter Tsolakides, given the inevitable learning curve.) Others will come aboard in time. Phil Rhoades may one day end up in its gleaming cryostats, upside down at minus 196C, surrounded by Allan and Barbara Pease, Elphie Coyle and Nadine Thomas, Peter Tsolakides and dozens of other Aussies. Who knows what distant shore these intrepid, deep-frozen travellers might one day reach?

For now, though, there is living to be done. Tsolakides, who has spent his retirement consumed with the task of getting the project up and running, is now looking forward to handing over the reins and enjoying himself. He and his wife are keen to do some travelling: they’re going to Europe, to see friends in England and to revisit their cultural roots in Greece. “We want to go back to the Greek islands, which are really beautiful,” he says.

The couple have been happily married for 46 years. She was by his side during all his overseas postings for ExxonMobil, in Japan, America, Singapore, Thailand and the UK. But there’s one journey she won’t be joining him on: despite all his entreaties over the years, she has shown no interest in cryonic suspension for herself. One life is enough. “It’s her choice, and I respect that,” says Tsolakides, a little sadly. He hasn’t quite given up, though; there’s “still time” to try to sway her, he says. Then he tells me her name: Athanasia. It’s a beautiful name, I say. He leans in, eyes twinkling, to share a little gem of cosmic irony: “Do you know what it means in Greek?” he asks. I shake my head. “It means ‘Immortality’.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout