Rosalind Hollinrake’s life and times: From Barry Humphries to Clarice Beckett, London to New York, it-girl to gallerist

How Ros Hollinrake found the work of artist Clarice Beckett in a cowshed and became her biggest champion is part of Aussie art world mythology. Less well known is her own remarkable story.

Rosalind Hollinrake and I are talking over cheese and terrine about her favourite Clarice Beckett painting, Wet Night, Brighton. The art historian, who rescued Beckett from obscurity and helped cement her place as one of the world’s great modernist painters, recalls a conversation with Fred Williams OBE – that eminent artist who did achieve international acclaim. Williams admired how Beckett had achieved a distinctly new way of perceiving the Australian landscape. He said quite humbly and with wonder at her Western District landscapes: “She got there before me.”

Hollinrake can sometimes seem as if she has known everyone. In conversation today she mentions Sidney Nolan, Australia’s greatest novelist Patrick White (a close friend whose intimate letters she destroyed at his request), as well as royalty (real and dramatic) and her former husband Barry Humphries, with whom she lived in London in the 1960s among the lions of the world of theatre and film.

That Hollinrake found, resurrected and championed Beckett – who died in 1935 at the age of 48 – is an art world legend. Less well known is Hollinrake’s own remarkable and compelling story, which ultimately led her to Beckett. Hollinrake has mounted groundbreaking exhibitions of the Australian painter’s work since 1971, and today is talking to me about Atmosphere, an exhibition currently showing at the Geelong Gallery. It has given me an excellent reason to meet up with Hollinrake, whom I first met almost 40 years ago. When I tell her I want to write a piece about her life, as well as Beckett’s, her tinkling, silvery laugh is on the edge of riotous and she says, “My life? What life? I should have married a farmer and had lots of children.”

After Humphries – with whom she had two daughters, Tessa and Emily – she married design engineer Ian Hollinrake, a notably gentle man, who died five years ago. It is their daughter Sophie who has driven her 86-year-old mother down from Castlemaine to my home in Hawthorn, not far from the house in Canterbury where she lived for many years.

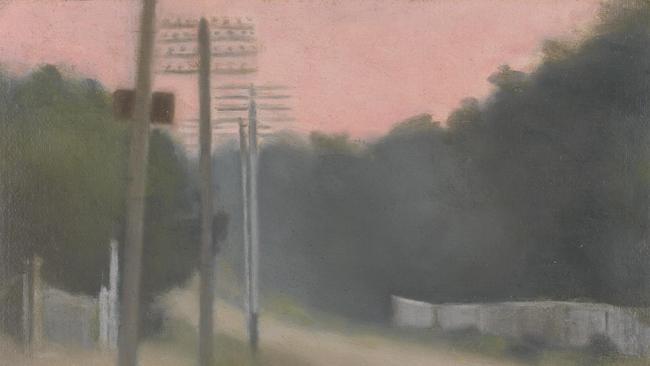

Hollinrake leaves the table to track down the adored Wet Night, Brighton (1928) in the catalogue she has brought with her, produced for the Art Gallery of South Australia’s 2021 exhibition of Beckett’s work, The Present Moment. “There’s her shimmering, vibrant, spiritual thing,” she says. “You think the road is going into the sea… I think it’s one of the most extraordinary paintings in Australian art history because who at that time would paint four poles to suggest a road leading into the sea?

“She has constructed this picture from four natural elements – light, air, luminous water and wood – to create a feeling of silence and mystery. Only the poles have substance and even they are somewhat spiritualised... Like all great works of art it holds itself in an atmospheric, ineffable silence, so hauntingly evocative that it can make for a transcendent experience.” After a moment, to further indicate the fathomless mystery of what she finds in Beckett, Hollinrake quotes TS Eliot: “I can only say, there we have been: but I cannot say where.”

I was a young man when I tutored Hollinrake privately while she was at the University of Melbourne in the mid 1980s, having gained special admission as a mature age student to study for an arts degree; later she would complete a doctorate, writing about Clarice Beckett. I remember her uncontrolled giggles when I played an audio recording of Vivien Leigh as Shakespeare’s Cleopatra: it reminded her of how the woman who brought to life Scarlett O’Hara and Blanche Dubois had also made a spoken-word recording of Peter Rabbit.

Hollinrake could captivate any social setting in the world with her mixture of intensity and repose; her cultivated manner comes with a devil-may-care moodiness that entranced a world of mighty artistic types.

She was born Rosalind Tong in a village on the outskirts of Auckland. “I was born in a cottage on an intensive mixed farming property. The village on Lucas Creek was 11km north of Auckland, with a sparse bus service and a ferry,” she recalls. “I started ballet classes at eight years old and went on my own to the city once I was shown what to do.”

In 1953 she became a foundation touring member of the New Zealand Ballet, pioneered by the Danish ballet master Poul Gnatt. She was offered a job at the Paris Opera Ballet on his recommendation and sailed for Europe in 1957, stopping off in Sydney, then headed to Melbourne, where she took a six-week contract with the musical Lola Montez while awaiting the boat to England. “I found the artists’ bohemian world both interesting and hilarious,” she recalls. Hollinrake didn’t ultimately have the career in ballet that she could have had. Might she have become famous? She insists she never wanted that. “I just loved dance. I still do.” (Today, she is hobbling a bit from recently attempting a hip-hop dance class.)

She met Humphries “on New Year’s Eve, just before it turned into 1958”. He was doing Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot with Peter O’Shaughnessy at the Arrow Theatre. “I ended up two months later living with a persistent Barry and working with him on Peter O’Shaughnessy’s fine productions, done on a shoestring.” The pair married the following year. “A day later we sailed for Venice on the migrant ship Toscana returning to Italy, hitchhiked through Italy to Athens and then to London. We arrived with no money and desperately hungry. Barry’s sister paid for a cab to her place and lent him twenty pounds.”

The pair found an agent and sought work. She remembers one night seeing Samuel Beckett across a bar, but choosing not to speak to him, she watched Humphries, who was captivated. In those early days abroad, she found work dancing and part-time cleaning and childminding jobs while Humphries chased roles, ultimately landing the part of the undertaker Mr Sowerberry in the original production of Oliver! and ultimately playing Fagin while working on his own shows.

“In 1963 we rented a cottage in Cornwall to work on Barry’s first tour of Australia – I had worked hard at persuading him that he could do it, after his amazing achievement in the Rock ‘n’ Reel revue [in Melbourne, 1958] as Edna Everage and then Sandy Stone. I armed myself with Women’s Weeklies from Australia House and lots of notes I’d taken at Earl’s Court at gatherings of recently arrived Australians, to keep up with language and types and what was happening back home.”

They completed the show while on a cargo ship from Rotterdam to Auckland. “We rehearsed the show at my parents’ home. My father gave us his dressing gown for Sandy Stone. It was perfect – brown wool, a quietly checked pattern.”

The pair shuttled from the Australian tour back to New York where Humphries was to play Fagin on Broadway. Hollinrake was pregnant for the first time and unwell. She remembers Peter Cook, who she had known in London, would call into the little pad the couple rented in West 10th Street Greenwich Village after his show Beyond the Fringe with Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett. It would be late at night but he would want to check “just to see if I was OK and feeling safe or needing anything as Barry was not always around. It was winter and I recall a horrific blizzard one night. The Cuban crisis was on, to add to the sensory experiences New York dishes up.”

Cook was “the kindest person” and Greenwich Village “fabulous”. Rock journalist Lillian Roxon took her to girls’ bars. “She and her friends were great fun but I wasn’t exactly partying as I suffered continual morning sickness throughout the whole nine months and was sick at night too. I also had mild pre-eclampsia.”

One night Cook and Humphries took her to a theatre performance in Harlem, “a rather dangerous area at the time”, she says. “Less dangerous, though,” she adds, “than a party where the scene was like something out of Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings of Hell, which was raided by the police.”

As Hollinrake came and went from London throughout the 1960s with Humphries – she worked on his 1965 and 1968 tours of Australia as well as the one in 1963 – she acquired an ever-wider circle of friends. She met Elizabeth Taylor at Lacy’s restaurant off Charing Cross Road, run by her close friend Margaret Costa. “Margaret placed us at the next table to Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, introducing a very shy me. They were pretty wrapped in each other but still pleasant with small talk.”

She also met Rex Harrison, who was compassionate to her when she found herself alone in Manchester one weekend. “Barry was performing in the preview of the musical Maggie May there and had asked me to come up with Tessa; I was pregnant with my second daughter, Emily. I tried to find him in the pub near the theatre. Rex Harrison was there and told me that Barry had returned to London for the weekend so I was rather stranded there in a couple of rooms that Barry had rented.”

One night in London she was in the kitchen at the house of her friend Robert Bolt, author of A Man For All Seasons and the film scripts for Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, who she had met through a close mutual friend, the sculptor Michael Kellaway. “I had been upstairs all night with baby Tessa while a Guy Fawkes party was in full swing in the garden. I came down to the kitchen at 1am when she had finally gone to sleep, to get a cup of tea and something to eat, as I was famished.

“Sam Spiegel [producer of The African Queen and Lawrence of Arabia], Diane Cilento and Bob Bolt were all in heavy discussion and I was drawn into opening up about my feelings and ideas on diplomacy and achieving peace and the whole Cuban crisis and the nuclear debate.

“I was very much motivated to come up with a solution to achieve world harmony. So naive. Sam got very excited and even rang the following day to follow through with his proposal for me to go to Russia with my baby as a young mother and speak with Nikita Khrushchev. None of us knew what really went on behind the scenes; we were all babes in the woods.”

Then there’s the time when the poet (later Poet Laureate) John Betjeman and his partner Lady Elizabeth Cavendish took her, as a surprise, to dine at St James’s Palace with Princess Margaret and her husband Lord Snowdon (the famous photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones). The princess opened the door. “I thought she was very pretty,” says Hollinrake. “She wasn’t short exactly, she was probably about five foot four, and she said, ‘Come through. Like a gin?’ And I said, “Yes, thank you, it’s a drink I love.” It was all very homely and then I suddenly realised the place was full of faded curtains which were all shredded at the bottom. She saw me looking in amazement and said, ‘My sister doesn’t open her purse often and if you try to put your fingers in it you might get them snapped off’.” She giggles at the memory. The princess drank gin and declared she wanted Hollinrake to take her to New Zealand.

In later years, when Hollinrake was back in Melbourne, Betjeman and Cavendish – who were “both really lovely to me. I was so fond of them” – visited her and her gallery. “We had some time together. I stayed in Derbyshire – Cavendish had a childhood home on the Chatsworth estate – twice after leaving England. The second time Ian came with me and was enchanted with the Chatsworth gardens.”

The London years were amazing, but the end of her marriage to Humphries was looming. She left him at the end of the 1968 tour, and ultimately established herself in Melbourne, opening a small gallery in a room in her house. Then, in 1971, she took a great risk by opening a stand-alone gallery in Armadale. It was here that she would be reunited with the work of an artist she had first encountered in 1965 when viewing a private collection in the ACT. She had been deeply moved by two paintings by “C. Beckett” (only one was signed) and intuitively felt the artist was a woman. Back then, inquiries among her artist friends had proved fruitless.

Now she reached out through journalist Keith Dunstan. “I knew him well, as I had a lot to do with the press during Barry’s tours,” she says. “To help me, he wrote a brief piece in his column in The Sun, saying I had opened a small gallery and I was seeking forgotten and unloved artists. The very next day, an elegant woman arrived at my gallery clutching a package in white tissue. In it were six small unsigned paintings, and she asked me if I knew whose works they were. I instantly knew they were Becketts. There was a very emotional exchange as she told me she was Clarice’s sister, Hilda Mangan.” It was serendipitous that Mangan had read Dunstan’s column.

“The next day we drove to the family property in Benalla where an estimated 2000 canvases and boards, mostly unframed, had been stored in an open-sided shed where the house cow had previously been milked – some on the dirt and some on a piece of concrete.”

Hollinrake estimates about two-thirds had been destroyed by exposure to the elements, rodents and possums. Many had been nailed up around the base of the house over the years to keep out the foxes and rabbits. “All the paintings had been originally stored in the farmhouse where Hilda had once lived and it was now her daughter and son-in-law’s place. They were astonished that I wanted to exhibit the paintings, assuming they must be worthless as Hilda had had no luck in trying galleries with them over the years. They had planned to burn them in a couple of weeks.”

Hilda also had a collection in her Caulfield unit. “We saw them the following day, and it eventuated that she had lent out paintings for care to friends, to Melbourne Girls Grammar [where Beckett went to school], to artist Justus Jorgensen at the artists’ colony Montsalvat. In time we retrieved these for future exhibitions.

“I knew it would be difficult for Hilda to sell the paintings, and then a very long path to keep Beckett’s work before the public and the art world at a time when women artists were not considered worthy of attention and auction rooms were not really promoting their works because they fetched pathetic prices. The focus was always firmly on male artists’ work.”

Recalling her first encounter with Beckett’s work, she says: “I felt I wasn’t looking at a painting, I was having an uncanny experience.”

She knew that one of them had to be of the Port Phillip Bay foreshore because of the quality of the dreamy grey tones and the winter light, so familiar to her. The paintings “moved me so deeply that I felt haunted by their consummate beauty and mystery,” she says. “Their effect on me changed the course of my life.”

The only parallel she could think of was the depth of emotion Mark Rothko elicited from the modulation of all those abstract pinks. “I’d seen his work in New York,” she says, “and responded to it so strongly. Now Beckett’s soft vibrating and floating bands of hazy tones and illusions of reality created that effect again.” All that exaltation and grief and majesty contained in a minimalist image. “But,” she adds, “there’s also the ecstasy and the transcendence.”

Her conviction that Beckett was a great universal artist was now unshakeable. She and Mangan worked to conserve what they could, and exhibited Beckett later that year and again the next year. It is the greatest act of recuperation and recovery in Australian art history.

Many more exhibitions followed, along with a monograph, talks, essays, the arts degree Hollinrake undertook to “gain a voice that was qualified to speak authoritatively about Beckett’s qualities as an artist and especially her importance in Australian art history”, as well as the doctorate and the biography she is writing.

“All those roads,” she muses now, as we look through the catalogue. “All those ominous telegraph poles in early morning light, those images of cars in Collins Street or St Kilda Road with a hushed twilight recreation of a world – urban, deliquescent, with no visible faces of drivers.”

Beckett had studied with Max Meldrum in the modernist Australian tonalist school. Hollinrake is very careful in describing how Beckett followed the very precise science he taught, of how to achieve the right tone in painting – he “just believed that there were the scientific facts, that anyone could paint”, she says – but there was also the extent to which Beckett also allowed herself room to move.

An important moment in Beckett’s artistic development came when she stayed with her friend Maud Rowe’s family at Naringal Station in Victoria’s Western District for six months in 1926. It was an environment in which she began to paint with more confidence. The eminent gallery director and art critic Patrick McCaughey describes Beckett’s Naringal Landscape from that time as “one of the finest nocturnes in Australian painting… There is no touch of melancholy here; instead a great calm, a deeply reassuring peace takes hold of the mood”.

“I used to talk with [painter] Sir William Dargie, who was my mentor, about how she gets such depth of feeling,” Hollinrake says. “He said, ‘It’s a bit like walking downstairs on a beautiful spring morning and seeing the morning sun come through the window and onto a vase of spring flowers placed on a table with a crisp white tablecloth. Her paint is healthy paint – you want to touch it’.”

Nothing is more characteristic of Hollinrake than the determined way in which, having discovered Beckett, she ensured her art was seen at last, establishing the towering claims that are made for it. She’s across every aspect of the artist’s work, and can effortlessly invoke her love of WB Yeats’ and Walt Whitman’s poetry, her theosophy, her Freudianism, the thousand faces of her sense of the uncanny as well as the mysterious quality of the everyday.

Hollinrake’s abiding passion is the reason the Geelong Gallery is able to hold Atmosphere, an impressive exhibition of a great painter. Her belief in the moral grandeur of Beckett’s art is absolute and, despite an innate humility, she knows the importance of what she’s done. It’s the truth Hollinrake finds in the beauty that burns bright and justifies the long road she has walked. b

Atmosphere is at the Geelong Gallery until July 9

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout