Clarice Beckett show in Adelaide is a must-see for any art lover

The dreamlike paintings of Clarice Beckett are being seen in a new, exciting light

Women artists were prominent in Australia between the wars, but most were eclipsed by the more aggressive and radical forms of modernism that emerged during and after the Second World War: painters like Grace Cossington Smith seemed slight compared to Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd or Russell Drysdale; Cossington Smith was fortunate, however, to live long enough to be rediscovered and celebrated in her later years.

Clarice Beckett (1887-1935) died well before the War and, although she had exhibited regularly in her lifetime, was almost completely forgotten until Rosalind Hollinrake’s chance meeting, around 1970, with her by then elderly sister Hilda, which led to the rediscovery of a vast cache of the artist’s work, over three-quarters destroyed by its storage in a farm shed exposed to the elements.

Beckett’s life had been uneventful but melancholy. As a well-to-do middle-class girl, she was free of financial constraints, enjoyed a good education and was allowed to study at the National Gallery School even though her parents, by all accounts, never really encouraged her artistic career and her father positively hindered it by refusing, for example, to include a studio in the new house they built at Beaumaris in 1919.

By this time her father had retired and her parents were in declining health so, as the unmarried daughter, the duty of looking after them and the house fell to her. Her time to paint was thus limited, and she never married or had children. Apparently her father even discouraged visits to the house by artist friends. Her life became still more difficult after her mother fell seriously ill in 1932 and then died in 1934.

Clarice, worn out by the trials of the last two years and grief at her mother’s loss, and with a weak heart as a result of rheumatic fever in childhood, developed double pneumonia after being drenched while painting in the rain and died at only 48 years old in 1935; the following year her father, despite everything, helped to organise a memorial exhibition for her and then he too passed away.

It was the exhibition at Rosalind Humphries gallery in 1971 that began Beckett’s rediscovery as an important Australian artist of the 20th century. The genuineness of the work was unmistakeable. But this was the high-water mark of post-painterly abstraction, so Beckett’s pictures tended to be praised as modernist because they were flat.

Needless to say there is much more to it than that. Beckett was not yearning for abstraction or flatness, but carrying on a tradition of landscape, indeed of plein-air landscape with, in her own mind, a devotion to rigorous realism or objectivity. And yet her conception of objectivity was – as far as we can tell from the very scant evidence we have of her life and thought – coloured by a lifelong interest in theosophy and spirituality.

And this is why she is far more interesting than the self-conscious modernists of the same period who reproduced the formulas of academic neo-cubism taught by epigones like André Lhote and Albert Gleizes in France. Her painting arises not from theories but from attention, and it is attention that it demands, in turn, from the audience.

The exhibition in Adelaide is designed to invite us into such a close communion with Beckett’s painting. After passing through a transitional installation space, we find ourselves before a single picture, Silent approach (c. 1924): in the grey light of dawn, we are on a road facing a shadowy figure, indeed a figure who is little more than a lacuna of shadow in the soft morning glow, like the figures in Seurat’s drawings.

The title alerts us, as the label rightly points out, to an implied aural environment, in fact an important if often overlooked element in landscapes: Claude Lorrain’s early picture in the AGNSW, for example, includes a waterwheel, a shepherd piping and goats butting horns. As we turn to the right, we meet the second picture in the exhibition, which continues this theme. The First Sound (c. 1924) suggests that the cart we see approaching on the road, with its horse’s hooves and wheels crunching on the gravel, is responsible for the first noise to break the deep silence of dawn.

The exhibition is designed around the successive times of day, and the first room is accordingly devoted to dawn, one of Beckett’s favourite times to paint, which was fortunate, since it was also a time that she could escape the house before her parents needed her. Often she would rise as early as 4am and drag her painting cart for kilometres to one or other of the spots she knew so well from years of early morning excursions around the shores of Port Phillip.

What she evidently loved about this time of day was not simply the low light and mist which soften forms and reduce tonal range, but more precisely the gradual reappearance of ambient and radiant light in the period just before the rise of the sun. With the slow increase in luminosity, colours, which the human eye can only perceive when there is enough light, start to return; but at first they are faint, low in chroma – and it is this mysterious, transitional moment when colour saturation and tone are still faint, that particularly appeals to her sensibility.

These liminal conditions drain the world of its solidity, and make it more elusive, like a dream or a memory. Even the most banal aspects of our modern environment acquire a symbolic resonance. Roads become figurative as well as literal pathways; telegraph poles evoke unheard voices and networks of messages. People, as we have already seen, emerge as visitations from another world, or phantoms of a lonely imagination.

Cars have a special place in Beckett’s work, and she is perhaps the only artist who has been able to make them poetic. This is partly because the body of the car, in Motor Lights (1929) for example, dissolves, leaving only its headlights seeking a way through the gloom, carrying unseen passengers. In Wet Evening (1927), the indicator light implies the existence of another road, perpendicular and invisible to us; red and white stripes on telegraph poles also seem to allude to roads or driveways at right angles to the one that stretches before us.

Boats too are particularly poignant. In Early Morning: The Fisher (c. 1930) the artist looks down to a beach where a fisherman is about to launch his small craft. In another tiny monochrome sketch, three men are putting out to sea in still dark conditions. We sense undertones of curiosity and yearning in the woman’s glimpse of a man’s life, a vision of hardship and toil, but also freedom and escape.

Beckett’s images of evening and sunset are similarly mysterious, only replacing the hope of dawn with the melancholy of twilight, but her vision cannot be explained by her choice of times of day alone. Just as important is her approach to the art of painting, rooted in Max Meldrum’s distinctive method and what he considered scientific optical naturalism. It is by extending this method that she evokes the transcendent and spiritual.

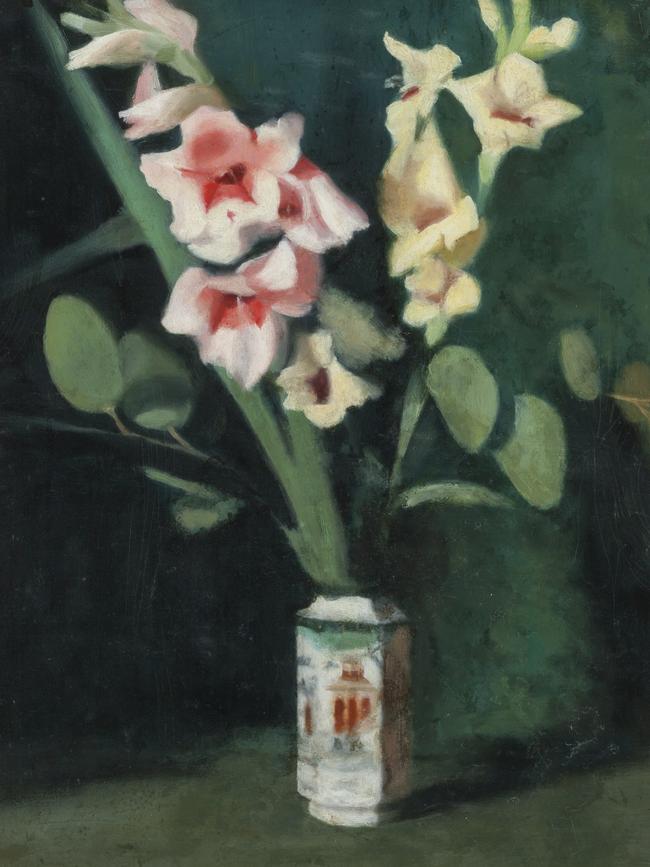

Meldrum’s method consisted in seeking to reproduce what the eye sees, not what it knows, and to reproduce these optical impressions as a whole, not as a collection of parts. Beckett’s floral still lifes probably allow us to understand the system best. From my own experience of watching a portrait executed in the Meldrum manner, I assume she would have set up the canvas next to the flowers in their vase, stood back a couple of metres to look, and then walked forward to place a mark on the canvas, then back again to see whether the optical effect of the mark matched that of the motif, and so on.

A set of remarkable photos in the National Library documents Meldrum’s method, and they go even further than this: not only has he set the canvas right beside the still-life objects on the table, but he is painting it within a frame and, even more unexpectedly, he has set up a matching frame in front of the motifs on the table. The frame helps the artist see the objects as already composed within the picture plane, and its blackness sets a tonal reference point for everything else in the painting.

This is the method that produces the strangely naturalistic and yet slightly blurry effect we find in Beckett’s still lifes, as in those of such fellow-Meldrumites as Colahan or Leason, without the sharp focus that would come from studying the flowers at closer quarters. They are only seen and painted from the intended viewing distance of the finished painting.

or landscapes, the system has to be slightly adapted, although it would still involve matching motif and image from the intended viewing distance of the picture. But there is also a more subtle adjustment of vision which is an extrapolation from the quest to see everything within the frame as a single whole. Of course all landscape painting involves seeing the whole view projected onto a single plane, unlike the natural way that we look, which is piecemeal and not only glancing from side to side, but changing focal length to examine things close to us or gaze out telescopically at those that are distant.

In practice, however, most landscape painters closely examine the parts as well as resolving them into a whole. Beckett, however, seeks only the whole, and this is why she sacrifices the parts and ignores all but significant details. It is this impersonal detachment – her understanding of objectivity – in counterpoint to the human resonance of the subject-matter, that gives Beckett’s paintings their distinctive poetic quality. More than this, it is what endows them with a sense of stillness and depth, as the painter’s eye is trained to be passive and receptive to the wholeness of the awakening world.

As I have observed before, a retrospective is also a test of an artist’s vision. Quite a few painters are diminished by surveys that lay bare the paucity of their poetic imagination. With Beckett it is the reverse. Taken alone or in small groups, her pictures are almost always engaging but can sometimes seem underworked or unresolved. Seen together like this, however, they are more like the notations of a spiritual practice, and thus the title of the exhibition, for once, is very apt.

Beckett’s paintings are indeed about the present moment; one can understand them as the visual equivalent of meditation, and like meditation, some days may yield deeper results than others, when the mind is distracted or not perfectly still and attentive. But all of them are records of visual and mental presence, in which wilful looking is suspended in order to discover the disinterested clarity of pure seeing.

Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment

Art Gallery of South Australia until 16 May

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout