On a crisp day last month a small group of men and women strode purposefully through the Belleme Forest in northwestern France. Among them was General Jean-Louis Georgelin, 74, the country’s no-nonsense former chief of the defence staff, who is now on one of the toughest – and most high-profile – missions of his long career. After the group paused in a clearing, two young foresters each took an axe to a towering oak. Then, wielding a handsaw that their great-grandfathers would have recognised, they brought the tree crashing to the ground.

The symbolism was poignant: this was the last of 2000 oaks to be felled across France that are destined for Notre Dame de Paris, which is being painstakingly restored after a fire four years ago that brought down its distinctive 96m spire and caused enormous damage to the gothic masterpiece beneath. The trees, many more than 18m tall, are being used to rebuild the spire, known as the fleche (arrow), and to recreate the intricate 13th-century wooden framework – the foret (forest) – that held up the cathedral’s roof.

They will rest, in part, on 1000 cubic metres of stone dug from the quarries of the Oise and the Aisne that replace those dislodged by the blaze. By the time the work has been completed, a further 41,000sqm of stone surfaces, 3000sqm of stained glass and almost 2000 statues and sculptures will have been cleaned and restored.

Everything about the restoration of France’s most famous cathedral is gargantuan – including the bill, likely to exceed the €846m (almost $1.4bn) that was quickly raised from 340,000 donors across the world. If the general keeps his army of workers on schedule, the spire will rise again over the next few months, with the cathedral’s exterior completed by the end of this year. “The return of the spire in Paris’s sky will, in my opinion, be the symbol that we are winning the battle of Notre Dame,” Georgelin declared recently.

It will not be until December 2024, however, that Laurent Ulrich, the archbishop of Paris, will again celebrate the Catholic liturgy in his cathedral. Some of the final renovations will not be completed until 2025. Plans to open in time for next year’s Olympics have been quietly dropped.

Among those who witnessed the blaze on the evening of April 15, 2019, was Patrick Zachmann, a photographer for the Magnum picture agency, who had been alerted by a friend and dashed across the city on his scooter. From his vantage point on the Pont de la Tournelle, a few hundred yards to the southeast, he had a clear view of the unfolding disaster. “It was gripping and at the same time terrifying,” he recalls. “We didn’t know how long the cathedral would go on burning or if it would collapse.”

The crowd on the bridge quickly swelled; some were crying, others praying. Zachmann, 67, is not a believer and before then had rarely set foot inside the cathedral. But as the flames spread and the spire teetered and fell, he appreciated the enormity of what was happening, and how hard it would be to imagine the city without a building that had been part of its history for more than 850 years.

“Notre Dame is a landmark for France and above all for Paris,” he said. “It’s as if a part of our memory went up in smoke.”

The damage done was colossal, not least because of a bungled initial response. A first warning light with the word feu (fire) flashed red on a smoke alarm panel at 6.18pm that Monday evening as a Mass was being celebrated before a few hundred worshippers and visitors, all of whom escaped unharmed. But a series of misunderstandings meant the fire brigade was not called until half an hour later. It later emerged that the man in charge of sounding the alarm had been in the job for only three days.

Initial suspicions as to what caused the fire centred on a possible short-circuit in the electrical wiring. There were then suggestions it could have been caused by a cigarette discarded by a workman (seven butts were found amid the debris). Investigators have since established the precise place where the fire broke out, but despite questioning more than 100 people have still not established the cause – though they have ruled out arson.

More than 400 firefighters tackled the blaze. Powerless to stop the collapse of the spire, they concentrated their efforts on saving the 69m-high north bell tower. Showing great courage, they entered it and beat back the flames, saving the structure, which, officials later claimed, had been moments from destruction. Another 100 officials and clergy helped to form a human chain to save the cathedral’s many treasures – among them a relic of the crown of thorns believed to have been worn by Jesus Christ at the time of his crucifixion.

Zachmann decided to document the drive to rebuild the cathedral that was announced that evening by President Emmanuel Macron. Two months after the disaster, Zachmann set foot inside and he has returned more than 100 times since to chronicle its transformation. Some of his pictures – a tiny fraction of the tens of thousands he has taken – are reproduced here; they provide an extraordinary record of the efforts made to save the cathedral from collapse and restore it to its former grandeur.

The fire was far from the first disaster to befall Notre Dame, which was begun in 1163 during the reign of King Louis VII, and largely completed 90 years later. By the early 19th century it had fallen into a terrible state: its original spire had been removed in the years after 1786 because it was in danger of collapsing. After the French Revolution three years later, the cathedral was desecrated and much of its imagery damaged or destroyed. When Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself emperor there in 1804, swathes of silk and velvet had to be hung over the walls to cover up the signs of disrepair.

Salvation came in the unlikely form of Victor Hugo and the publication in 1831 of his book Notre Dame de Paris – known in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Hugo’s revelations about the cathedral’s condition prompted a public outcry and the decision a few years later to restore it. In 1844, a jury awarded the contract to Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, a 30-year-old expert on gothic architecture, and his fellow architect Jean-Baptiste Lassus.

The pair faced a dilemma: the cathedral had already been modified considerably since its completion in the 13th century, so there was no question of returning it to an “original” state. Instead they made changes of their own to the interior, while outside they added chimeras to the famous gargoyles highlighted by Hugo in his novel. The most visible addition was a new spire, taller than the first and designed to better withstand the weather. At its base, Viollet-le-Duc placed representations of the four evangelists and statues of the 12 disciples; the face of St Thomas, the patron saint of architects, bore a remarkable similarity to his own.

The day after the 2019 fire, Macron vowed: “We will rebuild the cathedral to be even more beautiful, and I want it to be finished within five years.”

The decision to appoint Georgelin, a military man, as his special representative, with an office in the Elysee Palace, was a sign of the President’s determination. During a long career, the general had supervised military operations in the Ivory Coast, Afghanistan, the Balkans and Lebanon. In early interviews he described the degree of co-ordination necessary to restore the cathedral as far more complicated, likening it to a “combat mission” and adding: “I must ensure that everyone, all those taking part in this battle, are mobilised to achieve the objective.”

It also helped that Georgelin is a practising Catholic. In accordance with the strict rules that govern the separation of church and state in France, the government is responsible for the cathedral’s structural restoration and conservation, but the Catholic Church is in charge of its interior. Notre Dame, the general declared, was “first and foremost a place of worship”, but it was also “the soul of France”.

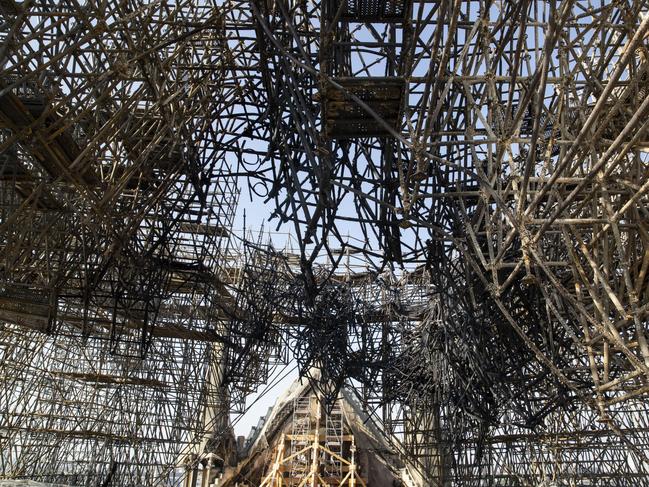

Many experts thought the cs deadline dangerously tight, arguing that 15 to 20 years would be needed for the restoration, almost as long as Viollet-le-Duc had taken. The scale of the task was certainly huge: the immediate danger of collapse had receded, but it soon became clear much of the structure was in a poor state and still in danger of falling down. The workers also had to remove 40,000 pieces of metal scaffolding, weighing 200 tonnes, which had been set up several months earlier in connection with a restoration project already underway at the time of the fire. These had been partly melted by the intense heat and, impossible to dismantle, had to be sliced into smaller pieces by cordistes – acrobatic steeplejacks hanging from ropes.

Zachmann was struck by the sight of the twisted metal during his first visits in June 2019. “It was all tangled up like a strange modern sculpture, quite scary,” he recalls. “It made a tingling sound when the wind blew over it. It was something I will never forget.” Amid the devastation, many of the chairs still stood in neat rows as they had for the Mass on April 15. Looking up, he could see the sky through large holes in the vaulted stone ceiling. “The sun shone through, creating this light and shadow never seen before,” he says.

Matters were complicated by 460 tonnes of lead in the roof and spire that had melted and been released into the atmosphere, which in the northern summer of 2019 forced a halt to the work for a few weeks. Lead levels of up to 100 times the normal background amount in Paris were detected in the courtyard outside; a study showed the wind could have carried particles up to 50km away, impacting the health of those in its path. At least two lawsuits have since been launched against authorities, accusing them of not revealing the full extent of the contamination and not doing enough to prevent it.

There were some miracles, however: Viollet-le-Duc’s statues of the apostles and the evangelists had been removed for restoration just days before the fire. The copper rooster that had perched on the summit was found damaged but intact amid the rubble, even though everything below it had melted away. The 8000-pipe grand organ, one of the biggest in France, also survived, though it had to be dismantled and cleaned. Rebuilding it will take a year, plus another six months to tune it.

While workers stabilised the cathedral, attention had turned to a more contentious issue: conscious of the way Viollet-le-Duc had put his mark on the building previously, Macron toyed with the idea of erecting a contemporary spire rather than merely replacing the old one. An international competition was announced.

Many of the suggestions that flooded in were as bold as they were shocking to purists. British architect Norman Foster, who put a widely acclaimed glass cupola on the Reichstag building in Berlin, proposed something similar for Notre Dame, together with a spire made of crystal and stainless steel. Building a copy of the fleche would be “going backwards”, he said. “The history of cathedrals is that every age had the confidence to make its mark. It’s a great tragedy, but also out of it emerges an opportunity.”

Stockholm-based Ulf Mejergren Architects wanted to cover the roof with a giant swimming pool that would become “a new meditative space”. The Paris-based practice Studio NAB suggested topping the cathedral with a greenhouse. Others came up with even wackier ideas. Roselyne Bachelot, the culture minister at the time, claimed Macron’s wife Brigitte “showed me a project topped with a sort of erect phallus with its base surrounded with golden balls”.

Overwhelmed by the hostility to the plans, Macron backed down. In July 2020 it was announced the spire would be rebuilt exactly as it was, using the same materials: 500 tonnes of oak for the structure itself and 250 tonnes of lead for the cover and ornaments. No one was happier than Philippe Villeneuve, the cathedral’s chief architect since 2013. He had taken issue with the President early in the debate, declaring: “For me, not only must you redo the spire, but you must recreate it exactly.” By then the onset of the Covid pandemic had already slowed things down. It was not until September 2021 that Georgelin was able to announce that the cathedral had finally been stabilised and the restoration proper could begin.

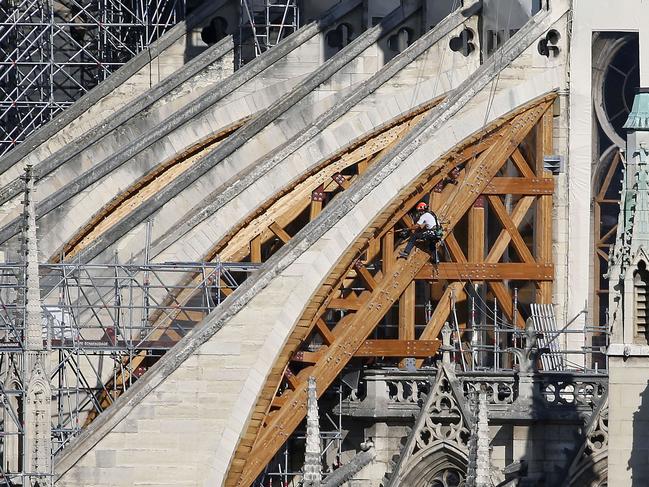

A workforce of about 1000 journeymen, ironworkers, master glassworkers, roofers, quarrymen, paint and sculpture restorers, carpenters and supervisors has been deployed, some 350 of them within the cathedral itself. A huge new set of scaffolding, weighing more than 3000 tonnes, has also been erected.

Their work has been facilitated by the use of new technology beyond the wildest dreams of Viollet-le-Duc: experts from the French National Centre for Scientific Research have created a “digital double” of the cathedral using laser scanners, some of them carried by the cordistes. Drones have also been used. The resulting 3D model, accurate to a few millimetres, has not only provided information to help with stabilising and renovating the building, it also forms part of a vast databank for researchers, who are learning much more about how the cathedral was built, including the recent discovery that its stonework is held together with 12 iron “staples” that form an iron skeleton. Dating back to the 12th century, it is thought to be the first of its kind.

So what will visitors see when they are allowed back into Notre Dame? Those who know its interior well will be in for some surprises. In 2021, heritage experts approved proposals from the diocese of Paris to update its look, which included installing 20th and 21st-century artworks among the old masters. The diocese also said it was intending to relocate the visitors’ entrance from a side door to the central portal. “The idea is that the faithful, or visitors, are first struck by the grandeur, by the beauty of Notre Dame,” Monsignor Patrick Chauvet, the rector at the time of the fire, explained.

Having quotes from the Bible projected onto chapel walls was also being discussed, as was moving the confessionals up to the first floor. The conservatives were once again enraged. In an open letter published in Le Figaro newspaper, some 100 public figures complained that the proposals were reminiscent of “immersive cultural projects where, often, inanity vies with kitsch”. Chauvet insisted there were no plans to turn the cathedral into Disneyland.

There will be changes, too, to the space around the building. Although the stone area in front of the cathedral will largely be left untouched, the surrounding streets will be made more pedestrian-friendly. During very hot weather, an innovative system will send a 5mm-thick stream of water across the stones in front of the building to lower the temperature.

Timbers from the last tree cut in February will by then have taken their place high in the roof of Notre Dame, in the cathedral’s own “forest”. “It’s an extremely moving and powerful moment,” said Remi Fromont, chief architect of historic monuments, when the oak was felled. “We have taken raw material in the form of a tree from the forest that will be made into a joist, which, I hope, will remain in the cathedral for many centuries.” b

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout