Mistress and apprentice: Nicole Kidman shows us who’s boss

The film star credits a stable home life for allowing her to take artistic risks in the erotic thriller Babygirl; but while Kidman craves the ‘cocoon’, Aussie co-star Sophie Wilde is ready to break out of hers.

“It’s a miracle,” beams Nicole Kidman, her crystalline eyes wide with delight. The actor’s face fills a Zoom window, at home in Nashville, off-duty in a slouchy grey hoodie. In another is the actor Sophie Wilde, on location in London, in the middle of making Alejandro González Iñárritu’s first English language film since The Revenant, a top secret project alongside an A-list ensemble that includes Jesse Plemons, Riz Ahmed and Tom Cruise.

That the schedules of two of Australia’s most in-demand talents have aligned at the busiest time of the year in order to meet our deadline, and mere weeks before they both return for Christmas – “the girls are coming home!” Kidman grins – is a miracle. The pair represent the once and future influence of Australians in Hollywood. Kidman is one of our last true movie stars, the astonishingly prolific queen of high and low, someone who can anchor the No. 1 series on Netflix (the trash-tacular The Perfect Couple) in the same week as she wins Best Actress at the Venice Film Festival for a provocative erotic drama called Babygirl. And Wilde is Kidman’s co-star in that movie, two years after she led the breakout Australian horror hit Talk To Me and was awarded Best Actress at the AACTAs for her unbridled, all-in performance. At 27, Wilde’s star is ascendant; Kidman, 57, was launched into the stratosphere some three decades ago and has reigned supreme ever since.

What was Kidman like when she was 27? “Well, I was married and I had a baby,” she sums up, wryly. (In case anyone needs reminding, that marriage was to Tom Cruise, whom she would divorce in 2001. Kidman has been married to Keith Urban since 2006). “I think, ’cos I’ve been working since I was 14, I probably felt I’d already lived a whole life. But I hadn’t really had the opportunities or the roles yet to form me. So I was still going, ‘I wonder if any of this is going to eventuate?’”

In her apartment in the London dusk, Wilde listens intently. “This has been a very surreal two years,” she begins, talking about a period in which she was nominated for BAFTA’s Rising Star award and received the Trophée Chopard at the Cannes Film Festival, a prize previously given to Florence Pugh and Anya Taylor-Joy early in their careers. “And in a lot of ways I’m figuring out acting, and figuring out how to do it, and I think that’s a lifelong pursuit. I don’t know if you ever really find the key that unlocks that. That’s why working with someone like Nicole is such a privilege.”

Wilde was nervous to accept the role in Babygirl, her first American production. Before Talk to Me’s premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival, she’d never been to the US. “My mum said, ‘Why don’t you take it as a learning experience? Why don’t you just sit on set and watch these people who you admire so much?’,” she recalls. For Wilde, Kidman is “Australian royalty”; Moulin Rouge is her favourite film. “It’s surreal to be able to work with someone who is such a big part of my love of acting.”

Kidman gazes beatifically at her. And that look is what made this interview such a tantalising prospect: it’s a chance to watch the interplay between two generations starring in one of the most talked-about films of the year, who both happen to hail from the land down under. Though she wasn’t involved in the decision to cast Wilde (rare, for Kidman, who has amplified her cultural impact as an actor-producer powerhouse on projects including Big Little Lies), she had seen Talk To Me and, she says, “been scared to death” by it. “Block your ears, Sophie,” Kidman warns, before launching into an avalanche of compliments. “She’s so present, and so skilled, and she’s completely even-tempered,” the superstar enthuses. “She’s able to take anything that you throw at her, and she just can flow. Which is the best thing as an actor. She’s got an enormous amount of talent.”

A few days later, The Weekend Australian Magazine is on the phone to Wilde again for a debrief after the joint interview with Kidman, who has become a champion for the rising star. When Wilde won the AACTA, Kidman sent her a long and gushing email, and at the Babygirl press conference at the Venice Film Festival, Kidman declared, of Wilde, that “it’s beautiful to see these young Australians coming up and taking a big bite out of the world that they deserve”. Wilde marvels at all this, like she still can’t believe her luck. “She’s such a beautiful support. You just feel held by her, which is a really nice place to be.”

There is a scene in Babygirl in which Esme, Wilde’s character, applies post-Botox concealer to her boss’s face, which is actually Nicole Kidman’s face. The film frequently shows Kidman’s character Romy, a trailblazing CEO of a robotics company – a powerful woman in a man’s world – pushing her body to the limits in the pursuit of physical perfection, with a cocktail of injections, cryo chambers and infrared saunas. In this respect, Kidman’s performance is remarkably unselfconscious and game, as well as rooted firmly in reality. Kidman describes Halina Reijn, the movie’s Dutch writer-director, as “a woman of this time, which I think makes it so exciting working with her”.

Wilde has described Babygirl as her own private acting masterclass, much of which took place in scenes such as this, when she found herself mere inches from Kidman. “The conversations we were having outside of the takes really helped curate the intimacy of that scene. And I was so appreciative of you creating that atmosphere on set and between us,” Wilde tells Kidman. “I don’t like ‘Action’ and ‘Cut’,” Kidman explains, jumping in. “I always see performance as constant … If it’s not filmed, it’s rehearsal. It’s just being within the body and soul of the character.”

Reijn praises the pair’s chemistry. “They are very different, but of course both very talented. Nicole is as experienced as it gets and Sophie is just discovering and exploring who she is as an actress, and that’s why I thought they would be a beautiful combination.” Reijn says she was “blown away” by Wilde’s performance in Talk To Me – “she’s funny, she dares to be ugly, she’s stunning” – and even more so when they met in person. “This is my actress,” Reijn remembers thinking. “She is going to be a huge star.”

Every scene in Babygirl is about power. The dynamic between mentor and protégé, the relationship between a female and male executive at the apex of a corporate hierarchy, a mother’s connection with her daughters – and the politics of the bedroom, which at one point sees Kidman on all fours lapping milk from a saucer. Romy’s character is a study in contradictions, which quickly telegraph her inner turmoil. Why, after clawing her way to the top of the corporate ladder, marrying Jacob (Antonio Banderas) and shuttling their children between a New York penthouse and a mansion upstate, is she so unsatisfied? Because, despite the tight grip she has over her personal and professional life, what her heart really wants is to surrender control. When Samuel, an intern played by Harris Dickinson, intuits this desire, an affair ensues that threatens to derail her perfect life. But she does it anyway. Like Kidman’s 1999 masterpiece Eyes Wide Shut, directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring her then husband Tom Cruise, Babygirl is a portrait of a person in psychosexual unrest. Both movies “are about existential crisis, one being the male protagonist in Eyes Wide Shut, and one being the female protagonist in Babygirl,” muses Kidman. “But they’re about marriage, actually.”

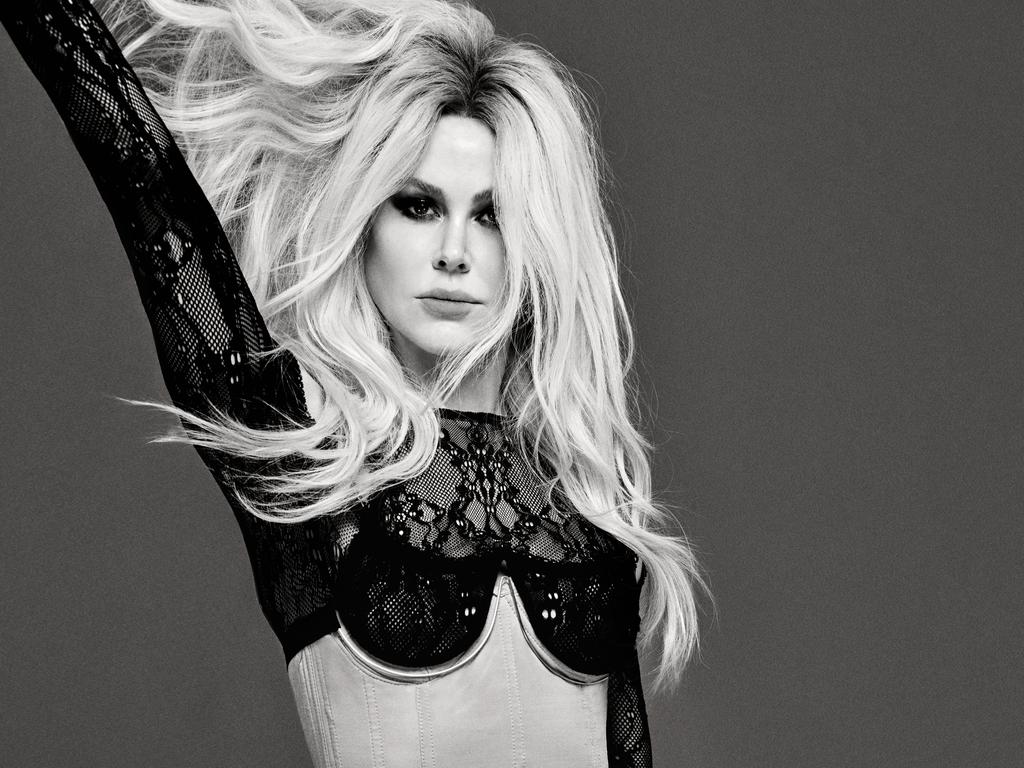

Much has been made of the sexual content in the film, but Babygirl is actually less risqué than it appears. The movie is more interested in what we talk about when we talk about sex: dominance, control, fantasy, shame. Still, the sex scenes are all trained on Kidman’s face, from the opening shot of the movie with its panting performance of a climax all the way through to the raw, unguarded orgasms Romy experiences with Samuel. Achieving this kind of vulnerability on screen is only possible, Kidman says, with a director you trust. “I had to feel that anything I gave her, she was going to value and take care of,” Kidman explains. “She wasn’t going to exploit me. And I felt that through the whole production. Any time I felt scared or nervous, I would go, ‘Halina, are we OK here?’ And she was like, ‘It’s OK. I’ve got this.’”

Reijn had an instant connection with her star. “There was a deep bond,” the director says. “Sometimes when you meet people you have admired all your life it can be a reality check – you go ‘Oh, they’re just human’. But with her, it was kind of the opposite. She was more angel-like than I ever expected, and so evolved spiritually, and of course an iconic talent.”

Kidman’s Babygirl performance has been hailed as one of her best: exposing and unpredictable, two things she does on screen better than almost anyone else. She has already been recognised with a Golden Globe nomination and the Best Actress prize at the Venice Film Festival. For Kidman, who became the first Australian to receive the AFI Lifetime Achievement Award last year, recognition still holds great significance. “The older you get, the better, right?” she smiles. She knows that nominations turn eyeballs onto this small film, with its boundary-pushing subject matter. “Because carrying this movie on your back, it’s scary,” she admits. “It’s a female-driven movie and it’s not a sure thing.”

Wilde is beginning her year with awards recognition too, with an AACTA nomination for playing Caitlyn, the object of Eli’s affection in Netflix’s Boy Swallows Universe. (She has already received a Logie for her performance). “It’s so strange, you grow up and you watch the AACTAs, and then you’re suddenly there yourself, and you’re like, ‘This is so inconceivable’,” she says. “I took my parents to Cannes and I almost feel like it was more special for them than it was for me. They were so, so overjoyed to be there. It’s really beautiful to be able to share those sorts of things with the people you love.”

As a child growing up in Sydney’s Inner West, Wilde was transfixed by Old Hollywood. She remembers feeling something spark inside her while watching Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck gaze into each other’s eyes in Roman Holiday; when her grandparents took her to see Opera Australia’s My Fair Lady, she refused to leave her seat at interval. “It changed my life,” Wilde laughs. “My grandparents were like, ‘It’s OK. We’re allowed to leave.’ I was like, ‘No. I don’t wanna miss it.’” At five, she was already enrolled in NIDA short courses and would later sign up for the Australian Theatre for Young People (ATYP), whose alumni include Rose Byrne, Toni Collette and Nicole Kidman.

It was after an ATYP production of Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth that Kidman first connected with Jane Campion, the New Zealand-born director who would become “one of my best friends”. Campion approached her to star in her student film; Kidman, then 14, turned her down. Later, Campion sent her a postcard that read: “I hope one day we will work together. Be careful with what you do, because you have real potential. Protect your talent.”

“I didn’t know what that meant,” Kidman admits, shaking her head. “When you’re young, and people are like, ‘Do this, protect this.’ I now know what that means. At the time, I was like – ‘What?’” She pulls a face. “People would say to me when I was young, ‘Oh, you’re going to be very beautiful one day.’ And I’d be like, that’s a horrible thing to say! Because I’d look in the mirror and go, ‘What? I’m covered in freckles, I’ve got red hair’. And they’d go, ‘No no, you’re going to grow into your face’. I was like, ‘Ugh, yuck’.” Now, though, Kidman realises: “Jane was right. I wish I’d been a little more diligent with some of the protection that I needed.”

Advice is something Kidman has always struggled with. “I have a very, very wilful nature, just because of the way I was raised,” she explains. “People will say something and then I’ll want to do the opposite.” Kidman won’t even offer guidance to Wilde. “She doesn’t need advice. The worst, worst thing is advice and being told what to do.” She peers at Wilde intently. “If you reach out and you go, ‘Can you help me?’, that’s different … Maybe that’s the mother in me, because I just know it’s very, very annoying people giving you loads of advice. But I would be there if she reached out and asked for help in any way. That’s important.”

Wilde’s face is soft. “I know you would.”

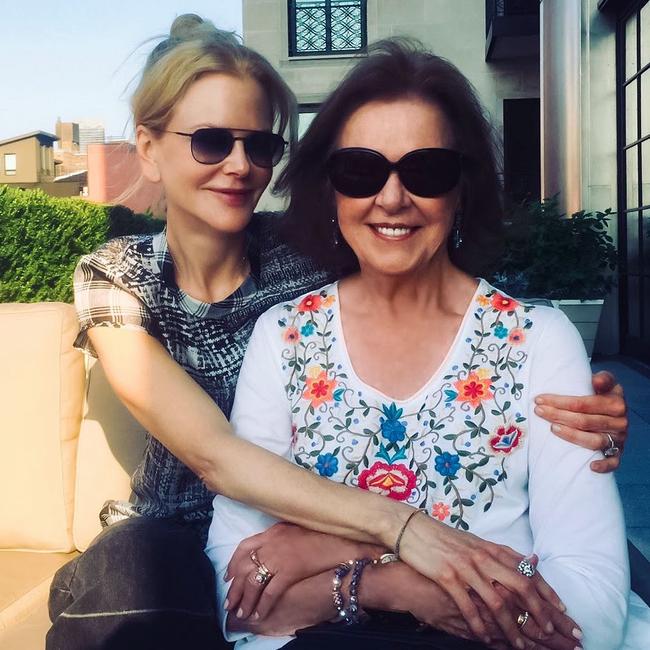

Like Wilde, Kidman was raised in a house surrounded by the arts. “I grew up with a mother and a father who took me to modern dance, art galleries, opera, theatre, independent film,” she remembers. “There was a theatre called The Independent on the North Shore, and we’d go and sit on beanbags and watch films. That’s where I saw things like Walkabout.” The Kidman family would then make their way home to Longueville where the critical discourse around the dinner table would begin. “We would dissect things, always, as a family. There was a lot of debate, and social awareness.” Kidman’s mother Janelle was a nurse and her father Antony a psychologist. “I think my parents, because of what they did in their profession, gave me access to people’s suffering,” she reflects. “Because I would sit in the hospital a lot waiting for my mum to finish her shift, so I would see things and get glimpses into people’s lives, which was really fascinating to me. And I always wanted to know more.”

Like Wilde, Kidman rocketed to global attention in an Australian thriller, 1989’s Dead Calm, in which she plays one half of a couple whose holiday is derailed by a murderous psychopath. Kidman has always been an intelligent and ethereal screen presence, transfixing at the moment her mask of perfection slips in the face of peril, even at the age of 22.

And like Wilde, whose first job out of drama school was in the 2021 miniseries Eden, most of Kidman’s earliest roles were on the small screen, in Vietnam and Bangkok Hilton. Her recent return to television, beginning in 2017 with Big Little Lies and culminating in her having at least one limited series on the boil at any given time about a wealthy woman harbouring secrets in the midst of a family breakdown – see The Undoing, Expats, The Perfect Couple, Nine Perfect Strangers and more – is, she smiles, its own kind of homecoming. “It never occurred to me that Big Little Lies was coming full circle, because I’d actually done that in Australia.”

These days, Kidman makes so much television because she loves flexing her producer muscle. She is currently in production on Scarpetta, the adaptation of the Patricia Cornwell thrillers alongside Jamie Lee Curtis and Simon Baker – “I’m always looking to give Australian actors work,” she says – while juggling new episodes of Nine Perfect Strangers, a miniseries called Margo’s Got Money Troubles set in the world of OnlyFans, and a much anticipated reunion with Reese Witherspoon on a third season of their hit Big Little Lies.

Kidman made television early in her career because it was a job, and it paid, and didn’t require her to go to LA simply to audition for a role, as was the reality when she was breaking out. “The idea of sitting in Australia going, ‘I’m gonna be an actor,’” she laughs incredulously. “It was like, ‘Yeah. And what’s your backup?’” Back then, Hollywood knew of only two Australians: Judy Davis and Mel Gibson. “And that was it,” she shrugs. “The pathway to that international career was a lot harder.”

There is another hurdle facing Wilde, as a woman of colour with Ivorian heritage, that Kidman never had to contend with. While Wilde says she has not had any overt experience of disadvantage compared to her peers, there have been micro-aggressions – “just as you experience in everyday life,” she notes, candidly – such as problems with hair and makeup artists. And, as Wilde points out, “I wouldn’t even know if I wasn’t getting opportunities because I’m a woman of colour, because they just wouldn’t be coming my way.” When she was younger, dreaming of becoming an actor, she saw Viola Davis win an Emmy for How To Get Away With Murder. “That was the first time that I was like, ‘Oh wow. Maybe I can do this’,” she reflects. “Before that, it was always a bit like, ‘I don’t know if I will have the same opportunities. I don’t know if I’ll be able to forge my own path in an industry that’s very white-centred’.”

Fear of failure was something that haunted Wilde early in her career. The most important thing she learned at NIDA was resilience. (“That was the key word. They were always like, resilience, resilience, resilience.”) “As a perfectionist, it’s really easy to want to get things right, and I think that’s counterintuitive to what we do. You have to be brave enough to fail, because that’s where you take risks and that’s where the most interesting kind of choices come out.”

Kidman gazes at Wilde in fascination. “Are you a perfectionist?” she marvels. “I’m not.” It’s why, Kidman continues, she could never have followed her parents in their love of medicine. “I would’ve been the sloppiest surgeon,” Kidman laughs. But not possessing a perfectionist streak is freeing. “That’s why I can go, ‘We’ll try this and try that, and just [be] quite crazy and random with choices’.” On set, Kidman steers clear of the monitor and doesn’t watch her own takes. “I stay very, very open and brave and bold in the sense of performance and not controlling it. It can either be a disaster,” she declares, ruefully. “Or it can be moulded so that it works.”

In September, as she landed in Venice to acceptthe festival’s Best Actress award for Babygirl, Kidman received the news that her mother had died at the age of 84. “This award is for her. She shaped me, she guided me, and she made me,” Kidman shared in her speech, which was delivered by Reijn, as the actor immediately flew to Sydney. “The collision of life and art is heartbreaking. And my heart is broken.”

Kidman closes her eyes at the mention of her mother’s death, which came 10 years after her father’s passing. “Ummm,” she begins, slowly. “I’m processing it. And sort of just going, ‘OK, this is very, very new’. There’s an emptiness. But it’s the reality of life and mortality. All of those things come in an avalanche; as I say in the movie [Babygirl]: ‘The avalanche is coming.’ And so the avalanche has hit me.” She pauses. “Both parents gone is a very different thing to one parent. But the beauty is I had parents that I loved, deeply attached to, and deep love. So with that comes enormous loss. And I always knew that was going to happen. The more you love, the more you’ll hurt. I’m in that now. It’s not all dark. It hits you at different times, it’s really weird.” Kidman stares into the distance. “Silence. Gentle silence.”

Wilde experienced grief, too, when her beloved grandmother Jane died in the middle of her gap year. “She was such an influential part of my artistic journey, and my love of performance,” remembers Wilde. Returning home for the funeral, toying with studying English and International Studies at the University of Sydney, she voiced a secret ambition to her father. “I was like, ‘Oh, you know, maybe I might audition for NIDA,’” Wilde recounts, her cadence hesitant. “He was like, ‘I think you should. And I think that Jane would be really proud of you if you did that.’”

There is an emotional catharsis to be found in performance, Wilde adds. “I’ve always been very shy, and I feel like acting has been a place where I can access parts of myself that I didn’t feel like I could access in real life.”

For Kidman, acting is a way to excavate the hardest corners of life, far from the cocoon of her everyday existence. “My life is quite normal,” she explains. “I tend to come back to my little home where I’m just a mother, and a wife, and a friend and a sister and an aunt, and all these other things. And then I go into this kind of extraordinary artistic life. And then I come back to my real life, which is very soothing to me. And that means I can go and explore things that maybe aren’t, because I have a very stable home. I keep it cocooned. Keith and I are very, very strong with our boundaries about how to create a home that is a very private home.”

The safety of that cocoon allows Kidman to take artistic risks; a movie like Babygirl is only possible when you have the cosy mundanity of Nashville to return to. “I’m always interested in what I haven’t done,” Kidman explains. “Where do we go from here? How do we get deeper and more interesting? And what is there that we haven’t discovered?’”

So, Nicole, where are you going from here? “To bed,” she laughs. “You know, my horizons have been so expanded in terms of being able to produce and work with people. I’m just on this journey of exploring humanity and my own experience in the world. I have no idea where I’m going, which is part of the reason I do it. I’m just that personality where I don’t really want to know. I don’t like feeling trapped. I don’t like expectations controlling me. I buck at that. I’ve always been like that … You can’t put a bridle on me.” She leans forward and smiles. “Or a saddle.”

Kidman returns to the cocoon; Wilde is ready to burst out of hers. “I’ve wanted to move to London for like four years now, but also, I’m on the move so consistently it just doesn’t really make sense for me to uproot my entire life and move to a city that I’m going to be in sporadically.” She still lives in Sydney, at least in the sense that her stuff is here. She will soon return to London to finish working with Iñárritu. “Post Babygirl, I had this realisation that I think I’d been taking acting so seriously that I feel like I’d forgotten to have fun,” she reflects. “And especially on this job, I’ve just come into it being like, I want to have fun. And it’s actually incredible how liberating that is. Not trying to get things right … Actually, I just wanna play.”

Babygirl is in cinemas on January 30

The Australian Plus subscribers cansave up to 50% on cinema tickets with Plus Movies, includes pre-sale tickets to the film Babygirl. Visit theaustralianplus.com/movies

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout