‘I’m scared I can’t do it’: Nicole Kidman’s confidence crisis

‘It’s shaping up to be either this enormously brilliant movie or this totally kyboshed turkey,’ one industry figure observed. How would you say it turned out?

To commemorate this masthead’s 60th birthday on July 15, we are counting down with a celebration of journalism over six decades. Today we look at reporting on culture and arts in the 2000s.

KIDMAN ON SONG

Our critic Lynden Barber has an early look at what would become one of the most celebrated Australian films of the decade.

- By Lynden Barber. First published March 17, 2001

Nicole Kidman was uncharacteristically nervous about starring in Moulin Rouge. Thrilled, yes, but also plagued by doubts about her voice, unnerved by the responsibility of carrying such an ambitious, large-scale movie production, especially when she had never before sung on camera.

At her first singing lesson for the Baz Luhrmann musical, singing coach Andrew Ross asked the Australian actor what she was frightened of.

“I’m scared I can’t do it,’’ she replied. “I said, Baz Luhrmann isn’t an idiot, he wouldn’t have cast you if you couldn’t do it’,’’ Ross says.

The Australian director, he added, was hardly short of choices, with “every major actress in the world’’ wanting the role.

Her crisis of confidence, although understandable in the face of a mega-production, proved ill-founded. The Australian this week viewed 14 minutes of footage from the heavily anticipated, made-in-Australia film, and one of the first things that became obvious was that Kidman can really sing.

Ross says he often heard people asking, “Oh, can Nicole Kidman really sing?’’. “You go, ‘Of course she can sing, you’ve just never heard her do it before’,’’ he says. The lead voices heard in the film were deliberately not tampered with in the studio in order to avoid Audrey Hepburn syndrome, adds Ross. (In My Fair Lady, Hepburn’s singing voice was dubbed by another singer.)

For months last year, rumours about the musical were seeping out of Sydney’s Fox Studios Australia lot and the backwash is still flowing.

“It’s shaping up to be either this enormously brilliant movie or this totally kyboshed turkey,’’ says one prominent industry figure after hearing the conflicting stories. “Whether it’s Heaven’s Gate or Citizen Kane remains to be seen.’’

There’s a lot hanging on this movie, and not only for its backer, Fox (with the remake of Planet of the Apes, this is one of the studio’s two big releases of 2001). In giving Luhrmann such an openly creative brief to make the film in Sydney with mostly Australian talent, Hollywood has made a huge leap of faith – one as big, if not bigger, than the one made by Universal when it backed George Miller’s talking pig film, Babe.

This is not only the biggest costume movie to be made in Australia but an attempt to revive a genre long thought to be extinct. For the Australian film industry, its success could mean more big projects made here under Australian control and bigger opportunities for local film talent all round. Its failure could mean the opposite.

In the film, to be released in Australia on May 24, Kidman and Scotsman Ewan McGregor play a nightclub siren and a bohemian poet in a tragic love story set in and around Paris’s late 19th-century nightclub the Moulin Rouge – famed for the cancan and the poster art of its most famous patron, Toulouse-Lautrec.

Although we don’t yet know whether the movie will be a hit or a miss, it is clearly no run-of-the-mill production. This is a film about a nightclub conceived as a kind of theme park. A nightclub whose curtains are pulled open by flying entertainers. (Yes, flying.) A nightclub containing, among other things, a club-within-a-club set inside the belly of a 15m model elephant. (The latter was inspired by a pachyderm in the Moulin Rouge’s garden that Luhrmann’s team uncovered while researching the real-life club.)

However the story turns out, the clips seen by The Australian make clear that we can at least expect something visually extraordinary. Moulin Rouge is clearly a movie filled with style, glamour, movement and colour.

CRUNCH TIME FOR MOVIE FANS

And the Academy Award for the most disgusting production in the modern film industry goes to … the bottomless bucket of popcorn.

Here is the scene that clinched the Oscar: you settle down in a typical Manhattan cinema to watch our favourite compatriot, Russell Crowe, in Gladiator.

As the film begins, a patron wedges himself into a nearby seat and immerses his head in a carton of popcorn big enough to sink the Titanic.

For the next hour or so the one sound you can hear above all others, over even big Russ’s battle cries, is that made by the relentless, slack-jawed mastication of popcorn. The crunch, crunch, crunch is punctuated only by the slurping sounds of finger licking. Your nostrils recoil from the smell of melted butter in the morning.

While wishing Russ would step off the screen, a la Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, and decapitate your tormentor, you tell yourself it has to end soon.

And it does. Like one of those carriage horses in Central Park, your neighbour emits a snort of surprise as their snout touches the bucket bottom.

But your respite lasts only as long as it takes for them to waddle to the concession stand for their free refill.

Now, I sometimes wonder whether my hatred of people eating, not to mention talking and rustling plastic bags, in the cinema is just mean-spiritedness.

Just because I prefer to watch films in silence and can survive two hours without food, why should others do the same?

Well, because eating and talking in the cinema is bloody inconsiderate, that’s why. There are complete strangers in close proximity who may not appreciate your bad manners.

Occasionally, a kindred spirit reminds you that you are not alone. Lauding the Julia Roberts vehicle Erin Brockovich, a Wall Street Journal critic described it as a film that “can make one forget, for more than 10 minutes or so, the odious smell and sound of popcorn crunching all round’’.

It is unlikely we will prevail, given popcorn is a $US2bn ($4bn) industry in the US, where the average consumer eats 50 litres of the stuff each year.

And you cannot blame the cinema chains for trying to sell more popcorn to recoup an unexpected cost. Adding 10cm to seat width has become a necessity in a nation where 30 per cent of the population is considered obese.

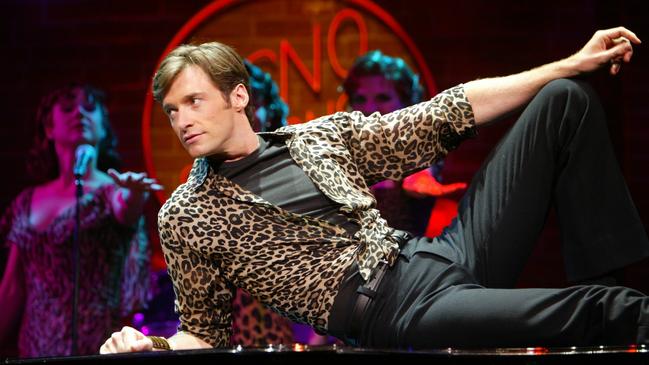

JACKMAN MAKES HISTORY ON BROADWAY

- By Rodney Dalton. First published June 8, 2004

Hugh Jackman gyrated his way into Broadway history last night when he became the first Australian to win the Tony Award for best actor in a musical for his portrayal of Peter Allen in the show immortalising the late entertainer’s life, The Boy From Oz.

The award caps off a remarkable year for Jackman, the star of Hollywood blockbusters Van Helsing and X-Men.

It is the first big win for an Australian since 1998, when Anthony LaPaglia accepted the best actor award for the Arthur Miller play A View From the Bridge.

The Boy From Oz was also the first Australian musical to play on Broadway.

Jackman accepted his award from Nicole Kidman and dedicated it to the flamboyant Allen.

“You wrote this song called Making Every Moment Count — you did it on stage and off stage. Peter, it’s an honour to play you,’’ he said.

Allen, who penned the song I Still Call Australia Home, died from AIDS in 1992.

As a performer at, and host of, the 58th Tony Awards, Jackman paid homage to Allen by repeating his 1981 feat of riding a camel on to the Radio City Music Hall stage.

After thanking his wife, Deborra-Lee Furness — “the best musical theatre widow a man could ever have’’ — Jackman also paid tribute to the late Sydney writer Nick Enright, who wrote the original book for The Boy From Oz.

“I know you are probably up there with Peter Allen having a beer … or a pina colada, I’m not sure,’’ he said.

Other Australians nominated for a Tony Award included Enright, Essie Davis for her lead role in the Tom Stoppard play Jumpers, and The Boy From Oz co-producer Ben Gannon.

Jackman’s award is recognition of the talent he brought to the Broadway production, which emerged as a commercial success despite receiving a lukewarm reception from critics when it opened last October.

The show received five Tony nominations, including for best musical, which went to the puppets of Avenue Q.

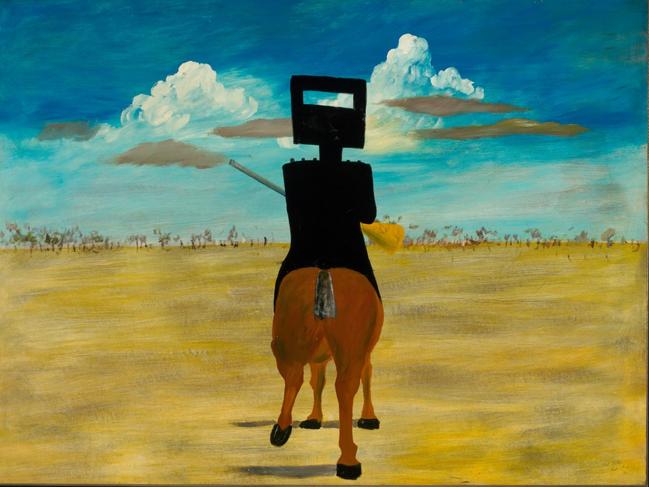

RISKY BUSINESS PAYS OFF FOR AUSTRALIAN WRITER AS HE CLAIMS SECOND BOOKER PRIZE

Years ago, Peter Carey claimed to be cool about literary prizes: “They can’t make any difference to the book which is already written,’’ he said blithely. “But I sense a great deal of excitement about fiction because of prizes like the Booker, which you did not feel 10 years ago.’’

That was 16 years ago in an interview with The Times. On Wednesday night in London’s Guildhall, at a chichi awards ceremony televised live on BBC2, Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang won its author what is arguably the world’s most famous award for literature — and Britain’s most discussed.

The lanky, bespectacled 58-year-old, decked out in evening dress like his lanky, bespectacled friend, rival and doppelganger Ian McEwan, was suitably self-effacingly pleased at scooping the $60,000 prize.

The five other authors on the shortlist, aware of television cameras on close-up, swallowed hard and smiled. Carey is the second writer to win the Booker twice, after South African J.M. Coetzee, who won in 1983 and 1999.

Following a silver service banquet, literati seated along the Guildhall’s white-clothed tables greeted the announcement with a mixture of unbridled enthusiasm and sage head-nodding. After going neck-and-neck with McEwan’s rather dull but technically brilliant Atonement, True History had taken a clear lead at the bookies in late September; Carey’s ambitious take on the life of Ned Kelly had long seemed a dead cert.

Ignoring the British critics, who complained that it was hard to warm to a criminal narrator with more pity for himself than his victims, the Booker judges duly rewarded the New York-based Australian for another of his big literary gambles.

“I have a dilemma,’’ Carey told The Guardian earlier this year, “in that I’m only interested in doing things that are risky, and then I’m always terrified of the risks”.

He needn’t be. Carey had previously won the Booker in 1988 with Oscar and Lucinda, and had been nominated in 1985 for Illywhacker. The accolades have been pouring in since 1974’s The Fat Man in History, a collection of short stories that hailed the emergence of a writer with a gift for ideas and narrative, one unafraid of tackling themes — identity and displacement, outsiders and underdogs — that were peculiarly Australian.