MJ The Musical faces up to Michael Jackson, the man in the mirror

In more ways than one, Roman Banks took on the most difficult role on Broadway when he was cast as the treasured and troubled pop icon in MJ: The Musical.

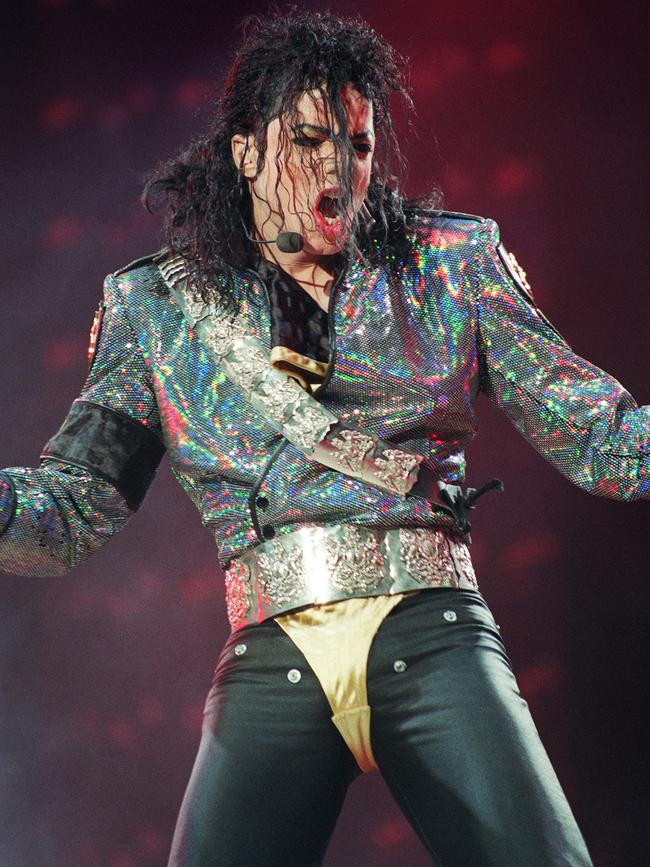

It is written into pop folklore that when invited to appear at a televised event marking the 25th anniversary of the Motown record label in 1983, Michael Jackson, formerly of the Jackson 5, agreed to sing with his brothers again only if he could do one of his solo hits too. He would perform Billie Jean alongside a new dance routine, while wearing a silver glove on his left hand, a sparkling sequined jacket on his back and a burning ambition in his soul.

What happened that night in Pasadena, before an effervescent live audience, was astonishing: Jackson debuted his “moonwalk”, the laws-of-physics-busting, backwards-gliding dance move that would become his signature.

The occasion was poetic: he would indeed reunite with his siblings for their former record label, but the only thing anyone could talk about afterwards is what the youngest Jackson 5 member, Michael, had done.

We’re still talking about what Michael did. It is an inescapable fact that if Jackson’s heart had not stopped beating in 2009, he would possibly be in jail today and his place in history would be reviled child rapist first, and genius musician second.

His death at age 50, however, clouded the questions about how popular culture should treat his artistic legacy, amid the seemingly irrefutable allegations that he sexually abused minors. The most serious and compelling allegations only came to light in 2019, a decade after Jackson died in Los Angeles from a cardiac arrest following a prescription drug overdose amid rehearsals for a planned 50-concert run at London’s 20,000-capacity O2 Arena.

In the usual manner of showbusiness, his death has been a boon for the business built around the discography and ephemera left in his wake. Record labels and publishers continue to profit from songwriters long after they’re in the ground, as platinum catalogues become diamond-plated in absentia.

The late star’s estate – as well as his mother, Katherine, 94, and his three children Paris, Prince and Bigi (formerly Blanket) – all furiously deny and defend against the allegations of abuse, while also seeking to retain ears and eyes on the best parts of the man. One of the most effective ways to do this is to keep his songs alive in the public consciousness. Not that they need much help in this regard: Jackson’s catalogue – including signature songs such as Billie Jean, Beat It, Thriller and Smooth Criminal – today attracts 52 million monthly listeners on Spotify alone, making him the 43rd most popular recording artist in the world.

As well as a film biopic planned for release next year – titled Michael, and directed by Antoine Fuqua – the other major project to carefully explore the artist’s troubled legacy is MJ the Musical. Both projects were undertaken with approval from his estate.

Written by two-time Pulitzer Prize-winner Lynn Nottage with direction and choreography from Christopher Wheeldon, MJ the Musical was in development for several years before opening in New York City in early 2022. It became a huge Broadway hit, and earned four Tony Awards; its estimated box office gross is in excess of $US230 million from 1.58 million attendances, which repaid the creators’ reported $US22.5 million investment within 15 months.

Subsequent productions have opened in London and Hamburg, as well as a US national tour. Its Australian premiere is set for early March at Sydney’s Lyric Theatre, with US actor Roman Banks cast in the lead role, in what might be the heaviest possible lift for a stage performer in any musical.

“We like to say that finding someone who can embody Michael Jackson is like finding a unicorn – and Roman is one of those unicorns,” says Nottage.

The Australian season will be presented by Michael Cassel Group, which produced the highly successful local runs of both Hamilton and Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

Adapting Jackson’s music, moves, looks and character for the stage seems fraught with risk, regardless of the accusations that dogged him later in his life. He is one of the greatest singer-songwriters and dancers of all time.

As a small boy he was the shining face and talent of the famous Jackson 5, which notched four consecutive No. 1 hits on the US Billboard 100 for the Motown label between 1969 and 1970. His early exposure to the twin pressures of fame and his disciplinarian father Joe – who also managed the Jackson 5 – led Jackson to develop a fixed inner narrative. He told himself, and inquiring journalists, that he’d never had a childhood.

This oft-repeated line gave a surprising amount of cover for why a grown man would come to prefer spending time with boys, alone. His level of comfort rose to holding their hands while in public, and sharing his bed with them for sleepovers at his ranch in California, which he bought for about $US28 million in 1988. He named it Neverland, after the island in the story of Peter Pan with his unending youth, the home of magical creatures and Lost Boys.

While his brothers also pursued solo careers, Michael eclipsed them all, earning 15 Grammy Awards and 13 Billboard No. 1 singles and driving worldwide record sales over 500 million. With his immense wealth and power came secrecy, seclusion and an air of invincibility.

His partnership with producer Quincy Jones (who died last month aged 91) for his disco-inspired 1979 album Off the Wall strapped Jackson onto a rocket. His 1982 follow-up album Thriller spent 37 weeks atop the US chart and yielded seven top 10 singles, capped by the title track – which was accompanied by a 14-minute musical horror film that came to define the music video era of MTV.

It is easy to see why Christopher Wheeldon, artistic associate at the Royal Ballet, would revel in the job of grafting Jackson’s revolutionary dance moves onto a new star. But the British-born director and choreographer was not blind to the red flags. “I had a lot of people in my life saying, “Don’t do it. You don’t need to do this’,” says Wheeldon, whose choreography for the one-act ballet An American in Paris was later adapted as a musical that premiered in the French capital in 2014.

“I’m not going to lie: I spent many a sleepless, sweat-filled night thinking, ‘Can we really do this?’,” Wheeldon says. “Because, of course, Michael’s so recognisable, even just starting with: where do you find the talents to play one of the greatest talents that ever lived? There were many, many moments of artistic fear.

“But I love a challenge, [and] I’m so thrilled that we took the risk and made the show. Aside from those fears, the process was just a delight: I learned so much from Lynn, I learned so much from Michael, and I’m thrilled that the show is now having this wonderful success.”

In Nottage’s book, MJ the Musical is set over two days leading up to the first show of Jackson’s 1992 world tour in support of his eighth solo album, Dangerous. This period marked a departure in the artist’s creative life, as the 14-track set – whose nine singles included Black orWhite, Remember the Time, In the Closet and Heal the World – was Jackson’s first album since 1975 without the guidance of the brilliant Quincy Jones. It’s the story of an artist desperate to prove himself. Spoiler alert: he does.

Sponsored by Pepsi, the 69-date stadium Dangerous tour was seen by an estimated 3.5 million people and grossed more than $US100 million, while its scope, scale and execution provided a blueprint for future pop stars such as the likes of Taylor Swift to stage their own generation-defining ambitious global tours.

Structured as a “mixtape of his life”, according to the playwright, the onstage device of an MTV crew filming and interviewing during the Dangerous tour allows the musical to slip into highlights of Jackson’s creative journey.

When asked by producer Lia Vollack if she’d be interested in writing a Michael Jackson musical, “it only took me, like, two seconds to respond with an ‘Absolutely, yes’,” Nottage tells The Weekend Australian Magazine. The opportunity for a deep dive into an artist who had soundtracked her life was impossible to pass up, despite the baggage that goes with the name.

“My life absolutely tracks musically with his: the very first album that I was introduced to was ABC by the Jackson 5. From then on, I became just a huge fan,” says Nottage, 60. “When I was growing up, there were very few pop stars who looked like me; who made music that spoke specifically to my heart.”

When it came to the writing, though, “one of the things that we definitely and very deliberately wanted to avoid was the classic ‘cradle to grave’ bio-musical, in which you feel you have to jam-pack it with every aspect of the subject’s life,” she says. “We wanted to find something that honours the ways in which Michael Jackson’s brain worked. He was interested in many different kinds of ingredients from different time periods. How do we do that? How do we find a vocabulary that not only tells Michael Jackson’s story, but also honours the way in which he thought about making art?”

These are weighty questions for any playwright to consider, but the stakes feel higher here. It’s difficult today to hear his name without reflecting on whether Jackson should be remembered as a genius or as a predator. And also: can both labels be true simultaneously?

Jackson was never found guilty of child sexual abuse, yet the material presented in Dan Reed’s 2019 doco Leaving Neverland was extremely compelling, particularly the interviews with two alleged victims, the Australian dancer and choreographer Wade Robson and actor James Safechuck. The star’s pattern of allegedly grooming, isolating, molesting and raping both boys – beginning at ages seven and 10, respectively – was revealed alongside corroboration by their regretful families, including the mothers who’d let Jackson into their lives and loved him like a son, even as he seemingly preyed on their boys’ bodies nightly behind closed doors.

The documentary caused a major stir on its release, forcing us to grapple with whether we could still comfortably enjoy the music after hearing the stories – in uncomfortably graphic detail – of how he had damaged those boys.

Leaving Neverland arrived midway through the lengthy development process for MJ the Musical. Asked how they navigated the uncomfortable truths presented in Reed’s film, Wheeldon replies: “It was definitely a hurdle in the way. We took pause, we had a little bit of time to really think it through. Then we sat down together, back at the creative table, and said, ‘OK, well, how does this affect the story that we were telling prior to this moment? And how do we move forward now that we know that this is out in the world?’ I think in many ways, it helped us to find more depth within our storytelling. So we forged ahead.”

When I raise this question with Nottage, she returns to a phrase that she says guided her writing: “Sustain the complexity.” It’s not an escape hatch per se, nor a dodge – but hovering in the background of our conversation is the understanding that MJ the Musical is a project approved by Jackson’s estate, which vehemently denies all allegations of sexual abuse and has sued HBO over the documentary.

“In writing it, there’s always noise that’s going to be in the back of your head,” she says. “That’s always going to be part of how we think about telling this story – and what I like to say is that all of the complications around Michael Jackson are the final collaborators.

“Everyone brings something different. And ultimately, as the writer, I can’t shape how people feel – all I can do is create this vessel, which is a musical, in which they can bring their emotions. They can bring their anger, they can bring whatever they’re feeling, and then have an experience that may allow them to celebrate, fall deeper in love – or exorcise demons. That’s my job: to tell a story that in some way [helps] people have some form of catharsis.”

That sounds like a tricky needle to thread, I say. “Mm-hmm,” she replies, evenly. “You know, that’s where the art is. That’s where the alchemy occurs. That’s an intangible thing: how do you tell a complicated story in a way that feels satisfying and engaging?”

But writing, choreographing and directing a musical based on the work of Michael Jackson still seems somehow dwarfed by the unenviable task of acting, singing and dancing like him on stage each night before a live audience.

Tasked with filling those shoes in Sydney will be Roman Banks, a 26-year-old American actor whose biggest previous break was appearing in High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, a mockumentary drama series that screened on Disney+. Not yet sufficiently famous to have a Wikipedia article tracking his career, Banks nonetheless impressed the producers enough to be offered the lead role in what will be his Australian performance debut, having previously sung and danced his way across US stages on a national tour that ended in July with 289 shows to his name.

In an hour-long phone interview from his home in Los Angeles, Banks presents as an articulate, thoughtful artist who understands the gravity of the role in all its complexities. “Thankfully, I wasn’t hired to portray Michael Jackson from zero to 50; I was only hired to portray two days of Michael Jackson’s life as a 31-year-old,” he says, referring to the eve of the 1992 world tour. “As much knowledge as I want to engulf myself with, at the end of the day I’m an actor whose job is to tell a story on stage,” he says. “Anything that serves that story, I’m going for it, I’m doing it. And anything that doesn’t serve that story, I don’t necessarily indulge with. We don’t ask anything of our audience but to come and watch. We don’t want to steer you to be a bigger fan; we don’t want to steer you to be less of a fan than you were when you walked in.

“As an actor, I just want to give you a story, and I want you to take that story and develop your own opinion on what you saw, and what you thought of what you saw,” he says. “There’s such a beauty to that, because it relinquishes us of any sort of real responsibility other than doing what we were hired to do: tell a story. And it allows the public to develop their own relationship with this sort of media, about this very complicated person.”

Banks, says the playwright Nottage, “is an astonishing performer. He has a singularly beautiful voice. He is a very good actor who really invested in taking the audience through the many layers of Michael – and he dances brilliantly. We joke that Michael only had to do maybe two concerts a week; Roman has to play Michael Jackson eight shows a week.”

Wheeldon, too, is full of praise. “Roman’s a beast,” he says. “He’s an extraordinary young man. He quite possibly is one of the strongest vocalists that we’ve had in the production so far. In its review of the opening night for the US tour of MJ the Musical, the Chicago Tribune wrote that “Banks offers a moving, vulnerable, emotionally centred performance … and it raises the stakes of what we are watching.” Later on in the tour, The San Francisco Chronicle would declare that “MJ is pop perfection. It also has an allegation-shaped hole … that it tiptoes right up to … then slinks away from on moonwalking loafers”.

Jackson preferred to record without being watched. Bruce Swedien, who engineered the 1982 album Thriller, recalled looking through the studio glass and seeing only a narrow cone of light shining directly from overhead, focused on the open microphone in the vocal booth.

Between lines, Jackson would be dancing in the dark, responding to the killer arrangements he’d crafted with producer Quincy Jones. At the precise instant when the song demanded his presence he would suddenly reappear in front of the mike, beneath the pin-spot, before flitting away into the shadows once more.

That striking image has taken on a haunted quality now, given what we have heard about his behaviour out of sight and away from prying eyes. In the light, Jackson embodied musical perfection complete with perfect timing; in the dark, it now seems, he became a vampire.

That uneasy feeling, the one that may have been swirling while reading this article, or even further back, since you first heard the allegations against Michael Jackson long ago? That’s the queasiness of being forced to try to reconcile two sides of Michael Jackson. Whether or not that feeling can ever resolve is unclear.

MJ the Musical is at Sydney’s Lyric Theatre from March 8, with previews from February 26.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout