Losing her voice, finding a cause: how Jenny Morris turned tragedy into triumph

Her chart-topping music career was cruelly cut short but a decade after she stopped performing this pop star has carved out a new creative life – one that changes lives.

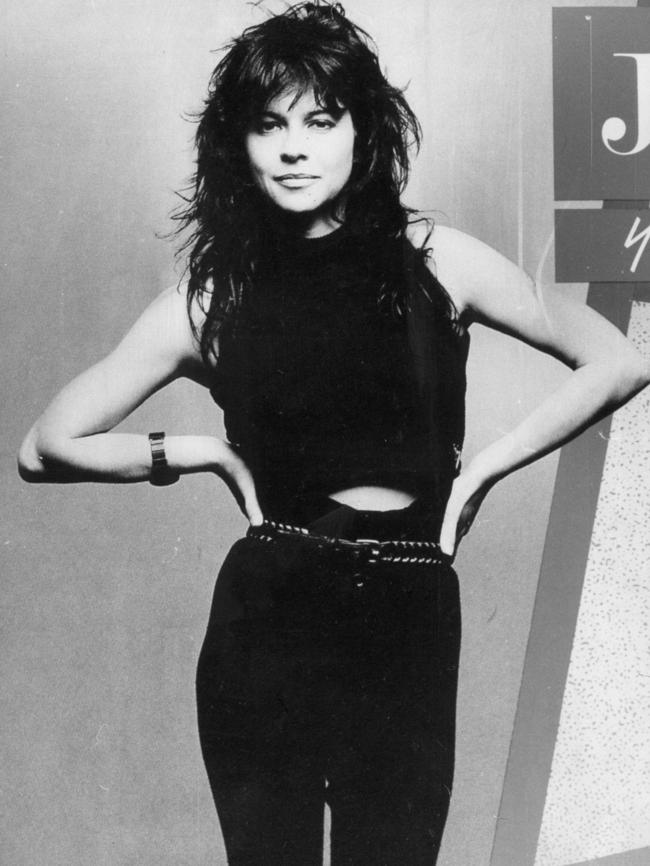

The trademark heavy fringe is the same today as it was in those video hits that dominated Sunday mornings back in the ’80s. The style is still insouciant; embodying elegance, rock royalty, and boss-lady chic in straight-leg jeans, high-heeled black boots and a simple black shirt. Her stature is diminutive – and this is the only time I will use that word to describe Jenny Morris.

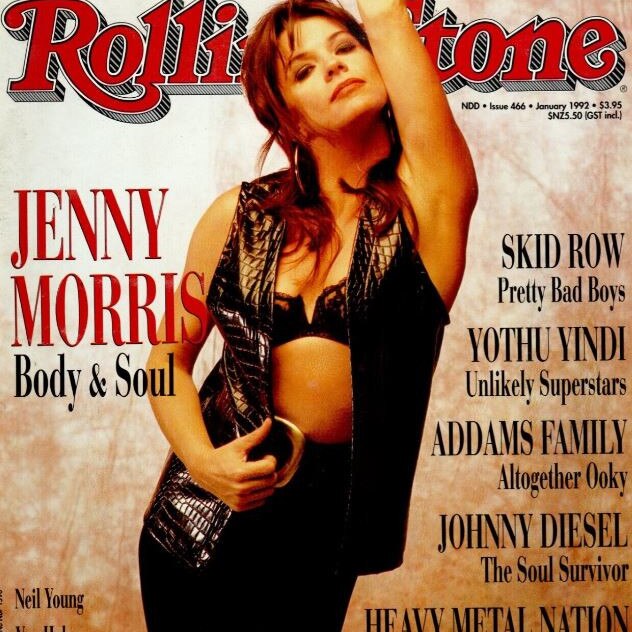

Her gift – a voice that carried hits such as Break in the Weather and She has to be Loved – made her a household name. She won ARIAS, one of which was handed to her by Elton John. She toured with some of the biggest names in music history, among them Prince (she was told never to make eye contact) and Paul McCartney (he kissed her on the top of her head, “like a dad would”). Her debut album, Body and Soul, went platinum; her second album, Shiver, went triple platinum; her third, Honeychild, went platinum again.

But almost before I get to speak to Morris for this interview, another famous voice is on the phone. “She broke ground for young female singers in this country,” Jimmy Barnes tells me. “She was always strong, and a great role model for them. She has been a part of the soundtrack of our lives and has carved herself a special place in Australian music history.”

In 2006 Morris noticed something changing in her voice. It was croaky all the time. She went for an endoscopy to check if she had nodules. She didn’t. The specialist sent her to a speech pathologist who diagnosed her with glottal fry, or vocal fry, and gave her some vocal exercises.

“I did the exercises but nothing changed,” Morris says. “After seeing the speech pathologist for six months, I went to her and she said, ‘I can’t understand why you’ve still got this thing. If I didn’t know better, I’d think it was this other horrible thing, which I won’t even mention, because for a singer it’s too awful to think about.’ And of course, that’s what it was.”

The walls of the apartmentin Sydney’s Potts Point where Morris lives with her photographer and art director husband, Paul Clarke, are plastered with art. Many of the works are gifts from the artists; some are pieces she picked up on travels with her tight-knit circle of friends. As she makes me a cup of Yorkshire tea to have with the Anzac biscuits I’ve brought over, I ask permission to slip into her bedroom to take a closer look at a painting by the late Nicholas Harding, a dear friend to both Morris and Clarke.

The painting depicts the road into Scicli, a small village in Sicily. In 2014 Morris and Clarke spent three weeks there with Harding and his late wife Lynne, and their friends, actor Hugo Weaving and artist Katrina Greenwood. Together, the three couples comprised a “cook club” in Sydney. They would gather to cook and feast on a new cuisine every few months. After a while, it seemed only natural that they should take the club on tour, and travel to the destinations.

“The light in the painting is perfect,” Morris says after bringing me my tea in a green Pantone mug. “It was late May so it was springtime. The light you see in that part of the world is bright and warm. You can see the caves, some of which are also people’s houses.” Every stroke of Harding’s trademark bulging brush contains a multitude of colours. It’s a painting you could look at for a lifetime and spot something new every day. It’s enormous, and takes up most of the wall directly opposite the couple’s bed. It’s the first thing Morris sees when she wakes every morning.

“It takes me back to the moment when we hopped out of the van and looked at the road into town,” Morris tells me as we settle inside a sunroom off her bedroom. The late afternoon sun streams across her desk, where, among the minutiae of daily life, sit two glass vases in which she is propagating Bonsai water lilies.

“I inherited the glass-half-full gene from my mother,” she says. “But for the first time in my life that was tested when we lost Nicholas, and then, within a year, Lynne too.” Harding died in November 2022 after a five-year battle with cancer. Within a year, his partner of 48 years, Lynne Watkins, was diagnosed with cancer and passed away too. It was a profound loss that impacted many, and devastated those that were closest to the couple and their son, Sam.

In addition to being a beloved friend, Harding was the first artist to donate work to Art of Music, a biennial charity event held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Since Morris founded the event 18 years ago, she has raised well over $2 million for Noro Music Therapy, a not-for-profit that provides music therapies to people with a range of needs, from dementia to autism.

When Morris started the fundraiser in 2006 she decided to pair two of her passions – art and music – by calling on visual artists to create artworks inspired by a piece of music, an album cover or a musician. It’s a roll-call of the biggest names in Australian contemporary art – Guido Maestri, Leila Jeffreys, Luke Sciberras, Holly Greenwood, Joshua Yeldham and more have contributed works. Every two years, the Grand Hall at the Art Gallery of New South Wales fills with Morris’ friends and fans – Sam Neill describes himself as “an Art of Music regular” and this year, ARIA Award winning singer Tina Arena will perform alongside Melbourne’s Sweet Talk and Brisbane indie-pop vocalist Jem Cassar-Daley. The auction includes a painting by Laura Jones - whose portrait of Tim Winton won the 2024 Archibald Prize - inspired by Nick Cave’s Where the Wild Roses Grow; and Vincent Namatjira, whose controversial portrait of Gina Rinehart in the National Portrait Gallery has recently made headlines worldwide, has donated a portrait of Archie Roach. Ben Quilty, who has donated a painting to every Art of Music since its inception, has painted Jimmy Barnes … again.

“He’s the worst life model I’ve ever had,” Quilty tells me over the phone from his home in the NSW Southern Highlands. “He just can’t sit still.” Quilty, an unabashed “fanboy” of Barnes, says they met through Art of Music. “The first concert I ever went to was Barnstorming, when I was 14. I think I’ve painted Jimmy six times now.” Quilty’s past portraits of Barnes have won the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize and been hung in the Archibald. “After Jenny took me out to the [Noro] centre, I was so moved by it. But it was also pretty clear to me that Jenny was fuelling her energy and the grief of losing her voice into doing something for people who have no voice.”

In 2006 Morris was diagnosed with spasmodic dysphonia, a voice disorder that causes spasms in the larynx. The extremely rare disorder can cause the voice to break, and sound tight or strangled. (Presidential candidate Robert F Kennedy Jr is a prominent person who also suffers from the condition.)

The disorder came on slowly, and Morris, with characteristic grit and determination, continued to sing and perform for as long as she could. “I’m sure the audiences noticed, and they were very kind about it,” she says, “but it got to a point where I just couldn’t sing anymore. Not properly, not without feeling embarrassed.” She performed her last show in 2014 at the Twilight series at Taronga Zoo. “Seeing the looks on my friends’ faces, particularly those who are singers, made it really hit home how bad this was,” Morris says. “And trying to make them feel OK about it was hard too. If someone told me that they were in that predicament I would be devastated. In some ways, it’s harder for the person hearing about it because the imagination makes it worse.”

“When you sing, it comes from your heart,” Jimmy Barnes reflects. “It reaches out and grabs people and brings them close to you. And to see that taken away from Jen was … it was brutal.”

“It really was very distressing,” Sam Neill, also a close friend, tells me. “It was so fundamental to who she was. It’s the last thing you would imagine would happen to her. And then there were 20 years of not being able to really hear what she was saying at dinner. And I really want to know what she has to say … I mean, she was, and is, a great artist. So it’s a loss, not just for her, but for all of us.”

There is no cure for spasmodic dysphonia. Over the years Morris has tried vocal exercises (she points to a shelf full of boxes with various voice exercise equipment) and has visited a clinic in Florida run by a speech pathologist who also suffers from the condition and takes a holistic view towards treatment. Early attempts at Botox injections in the throat did not help; however, when she tried the treatment again at a clinic in Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital two years ago she found it gave her relief. “My lovely therapist there knew exactly where to put the needles and I have gone to him ever since. It’s been almost two years now that I can speak without blocking.”

Over the many hours that we sit together and talk, I have no trouble understanding her, and she doesn’t need to take a break from speaking. “She is a force of nature,” Neill says. “It is extraordinary that in spite of everything she’s remained an optimistic, marvellous person who’s always good company.”

Jenny Morris was the 10th baby born in the new maternity ward of the Tokoroa hospital, on the North Island of New Zealand, in September 1956. Hers was a bustling family of eight siblings, and while one child died in infancy, and a much-loved brother died in a car accident when Morris was 13, she brims with happiness when she speaks about her childhood.

“We were all very close, always singing together and doing harmonies while we did the dishes. Our home was down-to-earth, full of laughter and music. We’d go and visit our favourite cousins in Whanganui and we’d be singing in the car along the way, in between big, chocolate-dipped ice creams at Taumarunui.”

The family lived on a dairy farm until Morris was six, when her father, Max, started work at an agricultural research station and relocated the family to the city of Hamilton. Her much-loved mother, Hazel, was an art teacher and a St John Ambulance nurse. “She would lay our carpet, put up wallpaper, she made all our clothes, she could do anything.”

Looking at Morris, I get the feeling that she could do anything, too. She was raising a young family – she has two children with Clarke, Bella (30) and Hugh (36) – while her star was on the rise. As we discuss her early successes she says, with characteristic humility, “I feel like it was a fluke that all that happened. I think the best artists are always the ones that have the ability to put their art first. I never had that. And if I’d had to choose I always would have chosen family.”

Morris has the down-to-earth quality I’ve noticed in many of her countrymen and women, but with a bent that is all hers – you get the feeling that she can see straight through any kind of facade. It’s more than a good bullshit detector, because it’s coupled with a softness; a sense that she’ll show compassion for what she finds on the other side.

Speaking of countrymen, when I ask Sam Neill what he has learnt from his long friendship with Morris, he pauses, then says: “Just how powerful a gentle personality can be.”

It is, perhaps, one of the many reasons Morris is respected without being feared, or perceived as – that word so often applied to impressive women – formidable. As the first female chair of the music rights management organisation APRA AMCOS, a role she has occupied since 2013, Morris has been voted in again every three years.

It’s a complex role. She is a regular in Canberra, reminding ministers and bureaucrats to remember the contemporary music industry when thinking about the economy. What has been her biggest win for contemporary music over the past ten years?

“Just before the last election Tony Burke asked me, ‘Tell me what you want, what’s going to help you, and tell us how we can give it to you.” In January 2023 Burke and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the restructuring of the Australia Council into Creative Australia which included $69.4 million funding towards Music Australia, a new entity dedicated to promoting Australian songwriters and bands. “It was f. king amazing,” she says, her eyes lighting up with the memory. “It was an ‘I see you’ moment. All these hardened music industry people were crying and so emotional.”

Some people remember the moment they found their calling but Morris says: “I just opened my eyes and I was singing.” She would fill notepads with poetry. After her brother’s death she started writing more. “My older sister Bronte bought me a guitar for Christmas with the pay from her first job. It made us all burst into tears.” Morris would later write She has to be Loved for her sister.

While studying to be a teacher in Auckland she joined her first band. “We were called How’s Your Father,’’ she says, then erupts with laughter. “It was a baptism of fire.”

In 1979, after moving to Wellington to work as a teacher, she joined the all-girl The Wide Mouthed Frogs, and soon after, The Crocodiles, who were about to record their album Tears. It was a hit and the band went on tour. First stop, Sydney. “And we just never left,” Morris says. After opening for bands like Midnight Oil and Moving Pictures the band broke up. Music producer Charles Fisher had taken Morris under his wing, and she recorded the single Everywhere I Go with the band QED. “And that accidentally became a huge hit.”

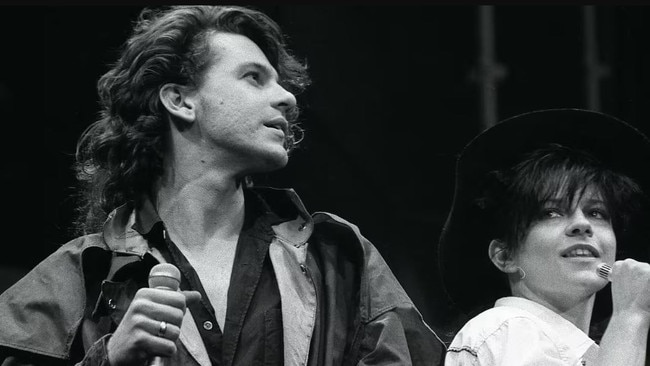

At the same time as her solo career was taking off, Morris had a couple of new flatmates move into her Paddington flat – film producer Michele Bennett, who remains a dear friend, and her then boyfriend Michael Hutchence. Chris Murphy, who was managing INXS and would manage Morris too, suggested she join the band as a backing vocalist on their upcoming tour. It was 1985 and INXS had released their album Listen Like Thieves. The tour crossed the US and Canada before heading to England and throughout Europe.

“When INXS were on fire, they were really hard to beat,” Morris says. “That tour was big enough for the band to feel proud of what they were doing but not too big for them to forget who they had been.

“When you get a public profile there is a lot of negativity that comes with that. And if your psyche or your character can’t deal with that, it can be very, very damaging … That’s what happened to Michael. In the later days, as we all know, it was horrible and it really got to him. I just felt fiercely protective of him because I knew what a lovely man he was.”

This year marks the first Art of Music without Nicholas Harding and Lynne Watkins, and it’s still difficult for Morris to talk about. Their son, Sam, has donated a large etching which will be auctioned separately, following a homage to Harding by his close friend Hugo Weaving.

“After losing Nicholas and Lynne I lost my optimism for a wee while,” she says softly. “But when it came back, it made me realise how lucky I am to have it. So while losing my voice and my ability to sing will never be something that I can talk about easily or flippantly, there’s so much more out there that I can draw on.”

She looks out the window – the sun is setting and there are birds singing as they fly across the inner-city rooftops – before dropping her eyes to her tiny water lilies. “I take a lot of photos of the drops of water on these and I’ll look at them over and over again. There is beauty in everything, everywhere around you. That’s the truth.”

And while this captures the glass-half-full mentality that she so often refers to, I can’t help but think that to have her positivity, in the face of losing so much, makes her cup much fuller than that. It overflows.

Buy Art of Music tickets at artofmusic.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout